Carving up the climate communication landscape

Warren Pearce’s new ‘Making Climate Social’ project seeks to investigate the ‘contributors, content, connections and contexts of social media climate change communications’ in order to determine ‘what the social media revolution might mean for the tricky relationship between science, politics, and publics.’ Warren recently invited me to take part in a workshop to discuss his project, and this post arises out of that meeting. Apart from providing an excellent opportunity for alliteration, what can research into social media tell us about the ‘contributors, content, connections, and contexts’ of climate communication? Four types of participation In considering that question, I have been thinking how to classify the different types of participation in climate change discussions. To this end, I adapted a …

UK Government running costs: High stakes, big claims, low transparency

In this post, Visiting Professor Christopher Hood and Research Officer Ruth Dixon consider why we should care about government administration costs, and call for greater transparency in the reporting of such costs. This article picks up on themes explored in their book, A Government that Worked Better and Cost Less? (OUP, 2015) which recently won the Political Studies Association’s 2016 W.J.M. Mackenzie Book Prize. High Stakes, Big Claims Every UK government at least since that of Margaret Thatcher over three decades ago has made much of its efforts to bear down on the costs of running government. Why? Just as those who give to charity want to see as much as possible of their money go to the intended beneficiaries rather than chief executives’ salaries, and investors …

The Evolution of Legislation: a Bioinformatics Approach

About thirty major pieces of government legislation are produced annually in the UK. As there are five main opportunities to amend each bill (two stages in the Commons and three in the Lords) and bills may undergo hundreds, even thousands, of amendments, comprehensive quantitative analysis of legislative changes is almost impossible by manual methods. We used insights from bioinformatics to develop a semi-automatic procedure to map the changes in successive versions the text of a bill as it passes through parliament. This novel tool for scholars of the parliamentary process could be used, for example, to compare amendment patterns over time, between different topics or governments, and between legislatures. Parliamentary amendments A major role of parliament is to scrutinize and amend …

The Evidence Paradox in Performance Measurement: When is a series not a series?

In a recent briefing paper on breaks and discontinuities in official data series in the UK, two of us [Dixon and Hood] highlighted the tension between the demand for quantitative evidence to drive performance improvement and the tendency to systematically destroy the very evidence by which performance can be evaluated. This paper was discussed, and further examples of data breaks across the public sector were explored, at a seminar at LSE in April, attended by senior civil servants and academics. The ensuing discussion embodied the same tensions, with some participants emphasising the need for indicator continuity, and others stressing that indicators must change as methodologies, purposes, and audiences evolve. Can this tension be resolved? In this article we suggest that recommendations arising from the seminar might point to a way to reconcile these demands.

Numbers that matter: Party leader satisfaction ratings and election outcomes

Satisfaction with party leaders of the two main parties would have predicted the outcome of the last nine UK general elections, including the most recent. This measure is worth looking at in more detail as voting intention polls led many forecasters astray in 2015.

Lord Ashcroft’s post-election poll (pdf here) showed the ‘three main reasons for voting’ for each political party in the 2015 UK general election. The biggest difference between parties was the number of people who voted on the basis that ‘the Party Leader would make the best Prime Minister.’ David Cameron, at 71%, far outstripped all his opponents, with Ed Miliband (the next most popular) coming in at 39%. On no other question did the Conservatives have such a large lead.

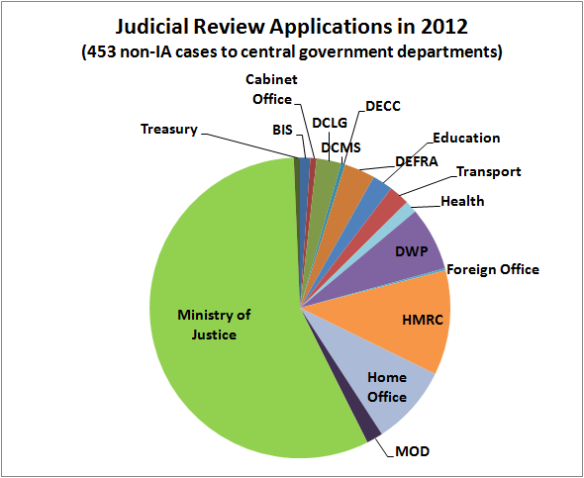

How Many Judicial Review Cases Are Received by UK Government Departments?

During the debate in parliament on Monday 1 Dec 2014, Chris Grayling (Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice) was asked how many Judicial Review cases are brought against government ministers.

Julie Hilling (Bolton West) (Lab): The right hon. Gentleman says “all the time”. Will he give us a notion of how often that is—once a day, once a week, once a month? How many times have such cases happened since April, for instance? He is giving the impression that they happen all the time, but what does that mean?

Chris Grayling: A Minister is confronted by the practical threat of the arrival of a judicial review case virtually every week of the year. It is happening all the time. There are pre-action protocols all the time, and cases are brought regularly. Looking across the majority of a Department’s activities, Ministers face judicial review very regularly indeed. It happens weeks apart rather than months apart.

The minister gave no actual numbers in his answer. So, in this post I’ve looked at how many judicial review (JR) cases were received by central government departments (‘ministers’) over the past few years. This analysis relates to my work with Christopher Hood in the Politics Department at Oxford.

Yesterday’s Tomorrows – What Happened to the Future of Government?

Christopher Hood and Ruth Dixon explain the results of their recent project aiming to assess the effects of successive efforts to reform the executive government (the ‘state machine’) of the UK over the past thirty years. This project explores how those reforms played out, and how far they delivered on what had been claimed and expected of them. How much ‘leaner and meaner’ was the state machine after a generation of such changes? Such an exploration is not only an interesting study in its own right; it is also significant for assessing the prospects for the future of government in the coming decades, for example in assessing how government changed in the periods of cutbacks in the 1980s and early 1990s in the context of what is likely to be a period of prolonged fiscal restraint in the 2010s.

Cutting the Costs of Bureaucracy: Are We Nearly There Yet and How Would We Know?

In 1955 G.A. Campbell wrote ‘[s]o long as officials obtained the whole or part of their income from fees, the total cost of the Service remained hidden. Parliament needed to provide no money at all for salaries in some departments, and where revenue did not balance expenditure it voted only for the difference. Under the new arrangements [after 1837] Parliament saw for the first time the wages bill of the public administration. The cost seemed to members of both Houses to be enormous. […] There has never since been a time when Parliament has not thought the Civil Service to be too costly and sought, more or less urgently, for economies in administration.’ (The Civil Service in Britain, Penguin, p. …