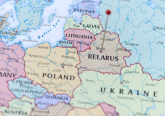

The EU looks, walks and talks like an empire. After extending its borders into Central and Eastern Europe, the EU has just created its third protectorate in the Balkans. From now on Greece will effectively be run by the EU the way Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina already are.

Empire is not a synonym of evil despite some bad historical connotations, especially from the colonial era. Power can be exercised in noble ways, and peripheries often prefer to be “conquered” than abandoned. However, the EU’s ambition to run dysfunctional countries by decree is doomed to fail and will represent yet another blow to the project of European integration. Formal involvement of the UN or the IMF in running the protectorates will not exonerate the EU.

Enlargement to Central and Eastern Europe has been successful because it empowered local actors. Fragile states were asked to adopt EU laws and regulations, but they were not ruled by “guys in black suits” from outside. The EU’s Balkan protectorates are not empowered but subjugated. Over the past several years Kosovo’s and Bosnia-Herzegovina were de facto governed by European officials. European institutions and EU members were by far the largest donors to these countries. They had their peacekeepers and police forces on the ground there. Most of the laws and institutions in these countries were set up and run under EU supervision. EU officials frequently intervened in detailed economic and fiscal provisions related to tax, customs or privatization. For instance, in Bosnia-Herzegovina the EU once created a ‘Bulldozer Committee’ to push through simplification of tax codes and boost public revenues with a country value added tax.

Emerging details of the bailout agreement for Greece envisage the same pattern of external rule. According to the prepared document cited by The Guardian “The [Greek] government commits to consult and agree with the European commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund on all actions relevant for the achievement of the objectives of the memorandum of understanding before these are finalised and legally adopted.” The EU conditionality will be updated on a quarterly basis, and each EU review will be fully specified “in detail and timeline.” The document stipulates that: “No unilateral fiscal or other policy actions will be taken by the [Greek] authorities. All measures, legislative or otherwise, taken during the programme period, which may have an impact on banks’ operations, solvency, liquidity or asset quality should be taken in close consultation [with the troika].”

Why have Mrs. Merkel, Mr. Dijsselbloem and Mr. Juncker embraced these policies? Protectorates are by their nature utterly inefficient. Parachuted external envoys do not understand local culture, have no access to local networks, and apply solutions ill-suited to local environments. Cheating is the rule of the game in protectorates. The metropolis cannot admit its failure, and it therefore pretends that things are moving forward. The periphery cannot do without external help, but implementing imposed policies is not practical either. Even the most euro-enthusiastic observers stop short of arguing that EU policies in Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina and now Greece are successful, but an exit strategy is feared even more than an ongoing stalemate.

Protectorates are also difficult to legitimate. This has something to do with their inefficiency, but chiefly with their political nature. Since local peripheral actors do not “own” policies designed in Brussels or Berlin they can hardly be held accountable for their failure. In fact, their political fortunes largely depend on relations with the officials from the metropolis rather than with their own electorate.

Citizens in the periphery know that changing their local authorities will not change the imposed policies and may even cause retaliatory measures from Brussels. Legitimization is also opaque in the EU’s metropolis. EU citizens may want to see their money being spent more effectively, but they only have instruments to discipline their own national politicians, and not the EU as such. Involvement of the UN or the IMF blurs the responsibility even further; much of the energy in the Balkan protectorates has been invested in squabbles between imperial institutions.

The Balkan protectorates have been created in emergency situations and the EU has not jumped into the region eagerly. In this sense, the EU may well be seen as an empire by default, but this can hardly justify the faulty arrangement. All three protectorates represent fertile ground for a different kind of predatory behaviour, economic and political, with little prospect for turning them into functional states and economies. (I am not even talking about genuine democracy here.) Above all, they make a mockery of the European ideal.

The EU was supposed to get rid of power politics and generate integration of its different parts. The Balkan protectorates represent the opposite values and they undermine the EU’s credentials if not the EU’s very rationale.

This article was originally published at Open Democracy.

No Comment