Politics as usual: women, media and the UK general election 2015

Politics has historically been dominated by men, and women have only relatively recently been elected to the UK Parliament in significant numbers. In order for women to be effectively represented in the political domain, they must also be adequately represented in the public discussion of political affairs that takes place in the news media. The ways women are depicted in news sends out important messages about their place and role in society and therefore, if women are absent or marginalised in political news, this reinforces their marginal status in the political process. Historically, women have struggled to achieve much visibility in electoral coverage, and by drawing upon data from the Loughborough Communication Research Centre’s real-time analysis of national broadcasting and press coverage, we can see that the 2015 election was no different.

How do editors choose which human rights news to cover? A case study of Mexican newspapers

The mass media forms a key channel through which instances of human rights violations are made public. However, the media can only publish a small proportion of stories, as media practitioners are required to sift through wider information, deciding what to cover. A media ethnography conducted in Mexico in 2006, before and after the presidential elections, can illuminate what journalists are trying to do in their human rights coverage and how their outlooks and contexts condition the incidents that are covered.

Parts of the Mexican media played a significant role in the country’s democratic transition since the 1976 Tlateloco Massacre, resulting in a general shift among journalists away from a cozy and financially lucrative relationship with the government. This led to the growth of new ‘market-oriented’, as opposed to ‘state-oriented’, newspapers. Both usually have a human rights beat investigating citizens’ complaints about infractions committed by state institutions. This often involves collaboration with the independent human rights commissions established in the 1990s.

Within this context, this case of Mexico suggests the mixture of outlooks and contexts affecting processes of extracting human rights news from wider information can be put into four categories: newsworthiness, journalistic aims, economic aims and political aims. A human rights story is more likely to be published by a newspaper the more it corresponds to these criteria.

The first factor, newsworthiness of a story, appears to be tricky to define; many of the editors interviewed claim it was a ‘sentiment’ that was ‘uncertain’, ‘improvised’ or ‘arbitrary’. Still, their explanations suggest some common criteria for newsworthiness. Firstly, published stories generally concerned incidents where human rights were transgressed rather than respected. One editor of El Universal explained ‘human rights are there to be taken care of … Therefore it is news when they are violated.’ Other aspects of newsworthiness included novelty, exclusivity, impact, representativeness, and timeliness. In particular, the potential political impact of a violation was considered greater, and therefore more ‘newsworthy’, if it involved multiple victims or was particularly severe, as in the case of a 13-year-old girl who was denied a legal abortion after she was raped. Editors also sought to publish stories that were representative of wider problems, such as inequality. The idea, as an editor of El Universal put forward, was ‘that when we talk of inequality or poverty, people have a point of reference’.

How to improve democracy in China? Start with a free press

Before joining the first cohort of students at the Blavatnik School of Government, I worked as a journalist for state-owned China Central Television, the biggest media outlet in China. Before that I spent four years working as a reporter and anchor for the Beijing Television Station, the local outlet for China’s capital city, also owned and operated by the government. Based on this, if I’m asked, about a single measure would strengthen democracy in my home country, I would firstly respond that you have to have more than one measure to reach that goal. However, if I can only choose one, I would definitely vote for free speech and an independent media.

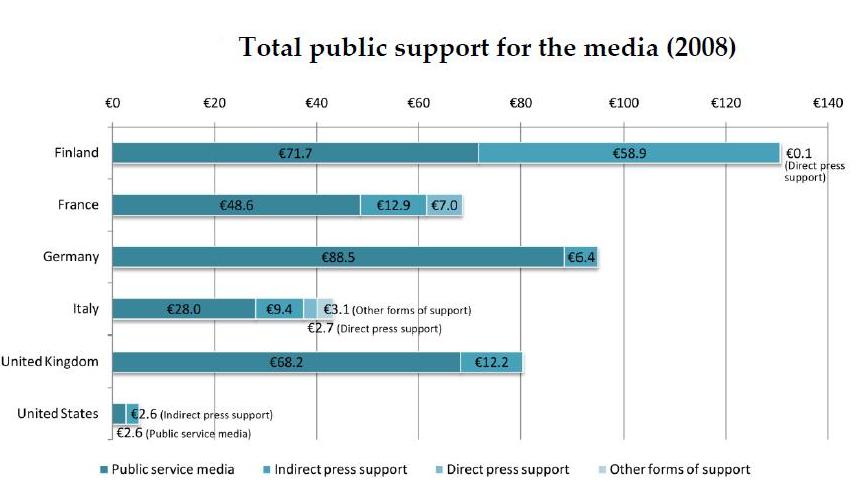

Supporting the past, ignoring the future? Public sector support for the media

Though Western media systems are going through a rapid and often painful transformation today with the rise of the internet and mobile platforms, the decline of paid print newspaper circulation, and the erosion of the largest free-to-air broadcast audiences, the ways in which governments provide direct and indirect support for the media have remained largely unchanged for decades. The bulk of the often quite considerable direct and indirect subsidies provided continue to go to industry incumbents coming out of broadcast and print, while innovative efforts and new entrants primarily based on new media receive little or no support. In central ways, public support for the media remains stuck in the twentieth century, and some parts of these support systems are …

Newspapers perform a valuable role in enforcing local accountability

In some ways this dichotomy might appear rather antiquated. After all isn’t everything online now and what difference do delivery systems make? But in reality we still see wide divergences between media organisations in terms of both consumption and production. First, consumption: The general tendency across many countries is that most people rely far more on TV than on the press for news. In the UK the disparity is very marked, with TV way out in front. Ofcom reported in 2009 that 74% of people in the UK used TV as their main source of UK news, way ahead of other news sources. More recent 2010 Ofcom figures surveying internet users showed TV ahead of the internet and newspapers as …

Social Media: No serious news-gathering operation can afford to ignore it

In the wake of the scandal currently afflicting Britain’s news industry, it is tempting to believe that anything might be better than putting our faith in the ethics and trustworthiness of professional journalists. So it is a good time to review what social media means for a news industry that is, to put it kindly, in a state of flux. As Tom Standage’s special report makes clear, social media and bloggers can contribute far more to news than was once thought. In recent years mainstream news organisations have often relied on them to break stories that professionals either couldn’t get to or didn’t know about, or to expose weaknesses or failures of interpretation amongst those same professionals. So there is …

News Media: Outside America, the future is much brighter

In the US debate over news there is an assumption among many that the Internet is killing news organisations. People point to the worrying figures about the numbers of journalists that have been laid off (with net newsroom employment down by more than 10,000 since 2007), the difficulties facing city and state newspapers, and to the dramatic decline of ad revenues. There’s no denying that these developments are worrying. But focussing on the US picture only tells a very partial part of the story about the relation between the news industry and the internet. The recent book that we produced at the Reuters Institute on The Changing Business of Journalism and its Implications for Democracy reveals that the US newspaper …

The Business of Digital Journalism and Why it Matters for Democracy

Many commercial legacy media organizations around the Western world are having a hard time these days, still hit by the impact of the recession on their revenues, and struggling with the different structural adjustments they will have to make as they move from the relatively stable and platform-specific media markets of the mid-twentieth century to the increasingly convergent and overlapping media environment of the 21st century. Newspapers in particular, from national flagship titles over regional powerhouses to local weeklies, are often in trouble. Changes in the business of journalism have potentially profound consequences for our democracies, because private media like newspapers have employed many of the journalists who inform us all (and occasionally misinforms us) about what goes on in …