Within hours of the unexpected death of Justice Antonin Scalia, lion of the conservative/originalist faction of the Supreme Court, political fur started flying over the nomination of his successor. Republican leadership (from key Senators to primary candidates) stated their firm opposition to an Obama nomination, arguing that the winner of the presidential election ought to pick his successor. The Democrats, for their part, put forward that it was a Constitutional requirement for the president to nominate someone to the Court and that they were shocked, shocked by Republican obstinacy. If the past is any indication, the Republicans can certainly make a credible threat that they will block an Obama nomination until the cows come home. But game theory tells us a different story; there is a distinct path for a successful Obama nomination to the Supreme Court.

The Upshot

In case you want to avoid a little algebra, I’ll preview the upshot here. It is in the President’s interest to nominate a centrist candidate; depending on the likelihood of the Democrats winning the election (currently a toss-up) he can always nominate a justice slightly more acceptable to the Republicans than the nominees they can expect (probabilistically) after the election, and secure a part of his legacy in the process. Moreover, once Obama nominates someone, should the likelihood of the Democrats winning the election increase, the Republicans will find it increasingly in their interests to choose the ‘sure thing’ appointee instead of risking the choice of President Clinton or Sanders. In the extreme case, should the Democrats win the presidential election, Republicans acting rationally should prefer swallowing their pride and approving Obama’s (centrist) nominee in the lame-duck session to being essentially forced to approve a more left-leaning nominee under a new Democratic president.

The Nomination Game

In order to understand the circumstances under which a Republican Senate would approve an Obama Supreme Court nomination, we need to characterize the game we are about to see play out. We need to lay out the players and the preferences, and how they will interact, in order to observe each player’s optimal strategy.

Player 1: President Obama

Let’s assume Obama’s goal, other things being equal, is to nominate as liberal a justice as possible. If we assume a conservative-liberal spectrum of 0 (most conservative) to 100 (most liberal), President Obama’s payoff will be the “liberalness” of the Justice he can successfully get on the court. Obama would also rather have one of his choices be appointed than none at all – we will give him a 10 point “legacy” bonus for scenarios where Obama is able to appoint a successful nominee. From the start, President Obama’s calculus will be affected by how likely a nominee is to be approved. In case his nominee is not approved, President Obama’s payoff from this game depends on who wins the election; if the Democrats win the election, Obama would still get what he wants (a pretty liberal justice), though he won’t get a legacy bonus. If the Republicans win, he gets no payoff.

Player 2: Republican Senate

Let’s assume that the Senate’s goal, other things being equal, is to nominate as conservative a justice as possible. On our liberal-conservative spectrum, the Republicans’ payoff for approving a nominee will be 100 minus the Justice’s liberalness score score, so a super conservative judge (0) gives them a payoff of 100 (i.e. 100 – 0). As with President Obama, if the Senate doesn’t approve a nominee, their payoff will depend on who wins the election.

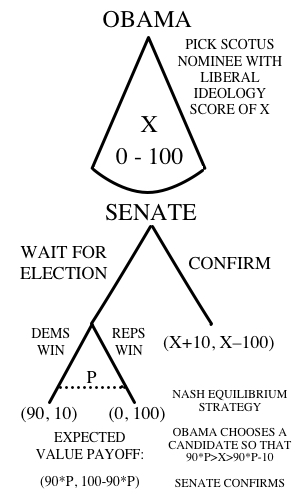

The Game

We can think about the nomination game as a three stage game. First, the president nominates a candidate with a liberal ideology score of x. Then, the Republicans decide whether to approve Obama’s nominee. If they fail to approve a nominee, then the election will determine whether the Democrats or Republicans pick Scalia’s successor. Within the game, both Obama and the Republicans will estimate their payoffs from the election by calculating the expected value of the election (which we’ll get into below).

The Payoffs

If the Republicans approve the President’s nominee, the President’s payoff is the justice’s ideology score plus a small legacy bonus (x + 10), and the Republicans’ payoff will be the justice’s conservative ideology score (100-x). If not, the choice goes to the American People. If the Democrats win the election, the Republicans are also likely to see their Senate majority erode, reducing further their ability to prevent a liberal appointment to the court: we’ll give Obama a payoff of 90 (for a pretty liberal justice) and the Republicans a payoff of 10. If the Republicans win, with a Republican congress, they’ll be able to nominate a very conservative justice; we’ll give the Democrats a payoff of 0 and the Republicans a payoff of 100.

But, remember, Obama will be choosing his nominee and the Republicans choosing whether to approve him or her before the election takes place; thus, in their payoff calculus, they will be using the expected value of the election payoffs, which is the outcome if the Dems win times the probability at any moment in time plus the outcome if the Reps win times that probability. For Obama, a little algebra tells us that his payoff is 90*P (where P is the probability of the Democrats winning) and, for the Republicans, it is 100-90*P.

The Strategies

This is where things get interesting. As long as there is a legacy bonus, Obama prefers a slightly more centrist justice that he can appoint to a more liberal one that he successor might appoint. But how can he pick a justice that the Republicans will accept? Using the expected value of the election to the Republicans. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has said “The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.” In reality, he might have appended “if that president is a Republican,” which is where he true preferences lie. The shadow of a potential Democratic victory moderates Republican expectations and makes them open to compromise; the longer a shadow, the more liberal an appointee they should be willing to accept, given on our liberalness scale as x = 90*P. At that point, Republicans should be indifferent to approving an Obama nominee versus waiting for the election.

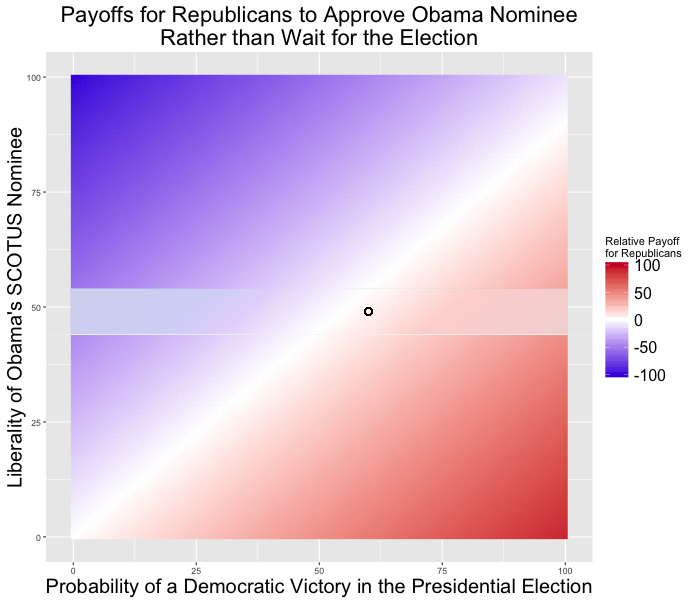

But the Republicans have another advantage; after Obama nominates someone, he cannot easily change his mind. Thus, the Republicans can stall in order to see which way the election is going. If Republicans’ prospects in November improve after that point, they will have no reason to approve a nominee. But if the Democrats look like they’re going to win, the Republicans will increasingly prefer a (centrist) Obama nominee to the choice of the new president. We can see this dynamic in the chart below (where the white zone reflects Obama’s preferences under the current likelihood of the Democrats winning according to the betting market PredictIt). The black dot represents Obama’s nominee; his or her “liberality” is fixed. If the Democrats likelihood of winning the election increases after Obama’s nomination, the black dot moves further into the red zone, reflecting a bigger relative payoff for the Republicans (the code for the chart is here).

Now in this game, the Republicans have every incentive to wait until the Lame Duck session (after the election) to approve a nominee. At that point, the probability of the Democrats winning the White House will be either 0 or 1 (in other words, they either will have won or not). If they have won, this position provides the biggest relative payoff for the Republicans (getting a centrist justice instead of a liberal); if the Republicans have won, obviously, they will wait to get a conservative justice. But President Obama can figure this out ahead of time; as Richard Lempert at Brookings has suggested, the President can put out a deadline after which he will withdraw his nominee in order to “let the American People decide”. If he does this, as the deadline approaches, the Republicans will have to make a decision, which they will do by comparing Obama’s nominee to the expected value of waiting for the election. If x < 90 * P (i.e. Obama’s choice is more conservative than the expected future nominee), the Republicans should vote to approve.

The Assumptions:

As with most political science models, the Nomination Game is a tool for helping us think, but makes some assumptions that might not play out in the real world.

- Shared beliefs about the probability of an electoral victory: The model assumes that President Obama and the Republicans share their beliefs about how likely it is for the Democrats to with the election. It is reasonable to believe that their beliefs are linked; DC politicos read many of the same polls and reports. And yet, as we found out in 2012 when many Republicans were truly surprised that Mitt Romney lost, these beliefs about probability can diverge because of cognitive biases like positivity bias or groupthink and because of the different information sources the different parties use. That being said, the essential game dynamic still works if Republican and Democratic beliefs are linked, even if they are not identical; it just makes a failure to arrive at a mutually beneficial payoff a little more likely.

- The probability of winning the election is independent from the nomination battle: This is the biggest leap the model makes. The model assumes that who the President nominates and whether they are confirmed does not affect the probability of one side winning the Oval Office in November. In reality, the SCOTUS nomination has surged to become a major campaign issue, and the dynamics of the nomination process are likely to dominate both Presidential and Senate races. However, it seems plausible that these two countervailing forces mostly cancel each other out; for example, the more liberal a Justice Obama nominates (energizing his base), the more the Republicans will be able to fundraise and energize based on defeating a liberal Justice.

- Reputational affects are negligible: The model assumes that the Republicans won’t really pay any costs for “caving” and consenting to an Obama SCOTUS nomination. That’s probably not true, though it’s not clear how strong and/or long-lasting a reputational penalty might be.

- Republican Caucus politics will not prevent a vote: Even if it’s in the Republican Party’s interest to approve a nominee, Mitch McConnell may have his own reasons to prevent a vote. This model assumes that he will not be successful in doing so. In reality, party leadership intransience probably lends a bit of “stickiness” to the model. A slim relative payoff for the Republicans will probably not result in an approval; however, a big swing towards a Democratic victory will generate significant pressure on the party, making it harder to prevent party defections towards a vote.

Like any model, the Nomination Game only imperfectly captures reality, but it does highlight one very important dynamic. If the Democrats surge in the polls after Obama nominates a (centrist) candidate for the Supreme Court, it will be increasingly difficult for Republican Senators to resist taking the sure thing and approving Obama’s nomination.