Pakistan: A nation defined by religion yet being torn apart by it

Pakistan was born a paradox. Its partition from India was considered necessary to ensure a homeland for the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent. However, its founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, always believed that Pakistan should be a secular state, tolerant of minorities; a homeland for Muslims but not an Islamic state. Unfortunately, he died shortly after partition and the dream of a secular and peaceful Pakistan was stillborn. 66 years after the establishment of the nation, the religious factor underpinning Pakistan’s creation and statehood has now become the principal source of its greatest national tragedy.

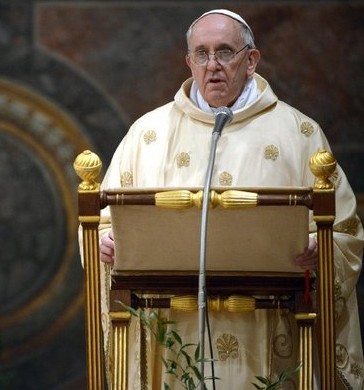

The utility function of Celestine V and the election of Pope Francis

When Pope Benedict XVI resigned in February 2013, there was much scrabbling by journalists to establish when last a pope resigned voluntarily. After a bit, they came up with the correct answer. It was in 1294, when the elderly hermit Pietro of Murrone, who had been elected as Celestine V after a two-year deadlock, abruptly resigned after five months and went back to being a hermit, a life he evidently preferred. But Celestine V was remarkable for two things, of which his resignation was but one. The other was his enforcement of the conclave. That distant event has decisively shaped the procedure for electing popes. To see why, we need to understand a lesson from social choice that papal electors learnt the hard way: the trade-off between stability and decisiveness.

What President Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory means for Kenya in the next five years

Following one of the most tightly fought elections in Kenya to date, Uhuru Kenyatta was recently announced as the country’s new president.

The news came after the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) conducted an audit of its final tallies to ensure it could rebuff the criticisms – made by supporters of second-place-candidate Raila Odinga – that some provinces had counted more votes than there were registered voters. Odinga’s Coalition of Reforms and Democracy (CORD) will bring their complaints to the Kenyan Supreme Court but their protests are being outweighed by the ‘thumbs up to polls’ given by the EU mission and the approval given by the African Union and Commonwealth observer groups. The recent groundswell of opinion supports their verdict: Kenya has a new president, who has been freely and fairly elected.

What does Kenyatta’s victory mean for Kenya’s next five years? There are big changes on the way that will challenge and re-design the country as we have come to know it.

The Italian Left: Reform and win, or perish

The general election has put the Italian Left in a state of shock. In December, the coalition led by Pierluigi Bersani had a fifteen points lead in the polls, while more than three million people turned up to vote in the leadership primary election. But last week’s election made that seem a long time ago. The final vote produced a new political reality: a hung parliament and the bitterest defeat for the Left in 20 years.

The vote spelled frustration at a whole generation of politicians. The parties which stood for parliament in 2008 collectively lost roughly 13 million votes. The centre-right parties lost more than half of their votes (about nine millions), even though Berlusconi managed a spectacular comeback by leading an unapologetic campaign. It proves that he can still dominate the debate. Mario Monti’s centrist coalition intercepted a further 2.5 million votes, mainly from the centre-right. The Democratic Party, meanwhile, lost 3.5 million votes compared to the last election, which also resulted in defeat. After months of successes in local elections and in the polls, the party portrayed itself as the only responsible force in a country in disarray. But just like Neil Kinnock in 1992, Bersani took the victory for granted. He ran a political campaign where the main objective seemed to reassure the party militants that a victory was finally at hand.

The Revolution Without Chávez: What are the likely scenarios?

The news of the death of Venezuela’s President, Hugo Chávez, has predictably received divergent responses from the international media. His passing was met with glee by opponents of Chávez – who claim that his presidency was characterised by personalism, economic mismanagement and autocratic leanings – and met with dismay by supporters of the President and the Bolivarian Revolution – who see the potential for the undermining of his legacy, the vast improvements in social indicators, the attempts to socialise the economy and the recovery of a left-wing alternative after thirty years of neoliberalism.

This polarisation of the international media reflects the political polarisation within Venezuela. While sections of the opposition partied in Miami, Chávez’s supporters filled plazas throughout Venezuela on Tuesday night and on Wednesday, thousands marched with the coffin on its journey to lie in state in the Military Academy.

What unites both points of view, though, is an appreciation of the pivotal role of President Chávez in leading the transformation of Venezuela since 1999. The most fundamental question, therefore, has to be whether the Bolivarian Revolution can survive without this key figure.

Launch of current issue of the St. Antony’s International Review (STAIR): “Power, the State and the Social Media Network”

The St Antony’s International Review (STAIR) is proud to announce the publication of its 16th issue, “Power, the State, and the Social Media Network”. The issue is available on IngentaConnect. The launch event will take place on 6 March at 6.30 pm in the Oxford Department for Politics and International Relations. In the themed section of this edition of STAIR five authors seek to shed light upon the contemporary relationship between power, the state and social media, perhaps the most pronounced and widely disseminated digital social technology the world has encountered. Supporting and affecting political movements from New York’s Zuccotti Park and Egypt’s Tahrir Square, “Facebook revolutions” and “Twitter revolutions” are conceived of as borne out of social media networks; they oscillate between the Charybdis of an anarchic freedom and the Scylla of surveilled repression, utilized by both citizens and the state. With such power, social media now holds the potential to empower and propagandize, secure and surveil, to create, and to destroy.

Predicting the Eastleigh by-election

Tomorrow the voters of Eastleigh go to the polls to select a new MP following the resignation of Chris Huhne. The eyes of observers of British politics are keenly trained on the outcome of the by-election because it might give us some early clues to some serious questions about the next election: How are voters going to respond when faced with two incumbent government parties? Is Liberal Democrat support going to evaporate? What is the effect of UKIP going to be?

Kenya: To the elections, and beyond (part two)

Two sides have formed in the run-up to Kenya’s March election. The first, under the Jubilee Alliance, is an alliance between presidential candidate Uhuru Kenyatta and his running-mate William Ruto, two experienced political leaders who are also suspects to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity conducted in Kenya’s previous election period. The second main side vying for election is a partnership between presidential hopeful Raila Odinga and his running-mate Kalonzo Musyoka, under the CORD Alliance (Coalition for Reforms and Democracy). This clash of titans has three possible outcomes