Spring in Sofia? Bulgaria’s struggle for social rights

Bulgaria’s constitution includes a wide range of social rights. However, the ‘democratic, law-governed and social state’ has been characterized as ‘chronically incapable of coping with its social problems or improving its level of economic prosperity’. Moreover, the Bulgarian neoliberal ‘minimal state’ often cannot provide its citizens even with basic necessities, such as food, electricity, central heating, or medical care. The post-socialist radical and extensive privatization and economic restructuringhave led to systemic impoverishment, decimating entire sectors of the economy and society.

The state often has appeared to be merely a prize that players try to capture rather than a guarantor of law and the basic services necessary for civilized and decent life. The post-socialist reformshave resulted in acute inequalities and disenfranchisement. With public discontent seemingly on the rise, strong social movements of ‘democratic populism’ and ‘redemptive radicalism’ increasingly capture the public vote.

More Europe, Less Europe, No Europe? – the inaugural Oxford DPIR alumni conference

On Saturday 2nd March Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations hosted its inaugural Alumni Conference. Former politics students were welcomed to the Manor Road Building for the chance to discuss the issue of Europe with the very best political scientists – past, present and future – that the University has to offer. Although this was a conference organised for the benefit of alumni, it could equally have served as an event to attract prospective students, such was the calibre of the speakers and the quality of debate.

You can listen to a podcast of the event on the DPIR website, see the full post for more details.

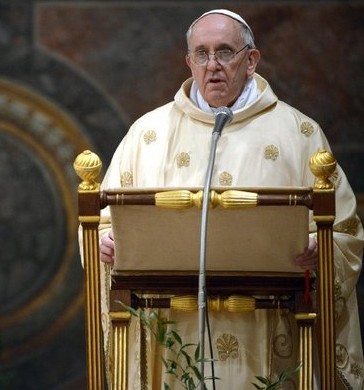

The utility function of Celestine V and the election of Pope Francis

When Pope Benedict XVI resigned in February 2013, there was much scrabbling by journalists to establish when last a pope resigned voluntarily. After a bit, they came up with the correct answer. It was in 1294, when the elderly hermit Pietro of Murrone, who had been elected as Celestine V after a two-year deadlock, abruptly resigned after five months and went back to being a hermit, a life he evidently preferred. But Celestine V was remarkable for two things, of which his resignation was but one. The other was his enforcement of the conclave. That distant event has decisively shaped the procedure for electing popes. To see why, we need to understand a lesson from social choice that papal electors learnt the hard way: the trade-off between stability and decisiveness.

The third phase of the Euro crisis

At the Spring European Council on 14/15 March 2013 the perennial issue of economic growth and jobs once again took centre stage. The President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, stated on Twitter that “Things are better than one year ago, but growth still worrying and unemployment unacceptable.” Mr Barroso is not the only top European politician who highlights the dire social situation in the crisis-ridden countries. In the margins of the European Council Jean-Claude Juncker, the Prime Minister of Luxembourg, warned of a “social revolution” that might result from the harsh austerity measures in Southern Europe.

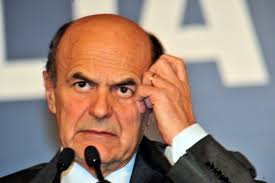

The Italian Left: Reform and win, or perish

The general election has put the Italian Left in a state of shock. In December, the coalition led by Pierluigi Bersani had a fifteen points lead in the polls, while more than three million people turned up to vote in the leadership primary election. But last week’s election made that seem a long time ago. The final vote produced a new political reality: a hung parliament and the bitterest defeat for the Left in 20 years.

The vote spelled frustration at a whole generation of politicians. The parties which stood for parliament in 2008 collectively lost roughly 13 million votes. The centre-right parties lost more than half of their votes (about nine millions), even though Berlusconi managed a spectacular comeback by leading an unapologetic campaign. It proves that he can still dominate the debate. Mario Monti’s centrist coalition intercepted a further 2.5 million votes, mainly from the centre-right. The Democratic Party, meanwhile, lost 3.5 million votes compared to the last election, which also resulted in defeat. After months of successes in local elections and in the polls, the party portrayed itself as the only responsible force in a country in disarray. But just like Neil Kinnock in 1992, Bersani took the victory for granted. He ran a political campaign where the main objective seemed to reassure the party militants that a victory was finally at hand.

Transfer union? That sounds familiar

Since the outbreak of the crisis it has become increasingly clear: Without financial transfers from the “rich North” to the “poor South”, the Euro zone, and eventually the European Union, cannot cling together for long. Equally obvious, this prospect does not make everyone exult, and not only in Europe’s economic powerhouse Germany the fear of a “transfer union” keeps simmering.

Interestingly enough, but largely unnoticed by outsiders, the Federal Republic has its own controversy over financial transfers from richer to poorer regions. In fact, the German fiscal equalization scheme is somewhat considered a failure by many observers. What can we learn for the construction of a Europe of solidarity?

Discussing the Procurement of Armed Drones: A very German-style deliberation

Germany is in uproar. The question whether to procure armed drones for the Bundeswehr is currently dividing the public and the political elite

It all began in August 2012 when German Defence Minister Thomas de Maizière, in an interview with the daily Die Welt [in German], stated his support for the acquisition of armed unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs or “drones” in popular parlance) for the German Bundeswehr. In the interview, de Maizière argues that the advantages of deploying armed UAVs are clear: “deploying an unmanned drone instead of a manned aircraft serves the security of our soldiers.” “[with UAVs], I can protect soldiers such as tank drivers or pioneers from the air.” [My translation]

The reason behind de Maizière’s public deliberations on this topic is a soon to expire leasing contract between the German Bundeswehr and Israeli Aerospace Industries (IAI).

The EU budget is a missed opportunity for Europe

Last Friday, after 24 hours of negotiations, European leaders agreed on a new EU budget deal for 2014-2020. Two summits were needed: one was held in November 2012, and another last week that ended in agreement. For the coming seven years, the member states will contribute 960 billion Euros towards the EU project—85 billion less than the European Commission’s original proposal. It is a flimsy budget, one by no means fit to deal with the economic challenges that Europe is currently facing.

It is quite understandable that countries such as the Netherland, Denmark and the United Kingdom aimed for a slashed budget: in times of crisis, it is hard to sell the message of pouring even more money into Brussels’ accounts. Indeed, the slash-the-budget-camp has proved to be quite effective in furthering its agenda.