Scotland: What will happen after the vote

At 650 pages Scotland’s Future is not a light read. It stands as the Scottish Government’s manifesto for a yes vote in the independence referendum. The volume ranges from profoundly important questions relating to currency and Scotland’s membership of the European Union, right down to weather-forecasting and the future of the National Lottery. Though it is likely many copies of Scotland’s Future will be printed, it is unlikely many will be read from cover to cover. Its authors probably do not regret its length: by its very heft, the volume seeks to rebut claims that the consequences of independence have not been carefully thought through. This post considers the immediate constitutional consequences of a yes vote in light of Scotland’s Future. Its central argument will be that the timescale proposed by the Scottish Government for independence following a referendum is unrealistic, and may work against the interests of an independent Scotland.

Q&A with Dr Cristina Parau: Why do politicians let judges have so much power?

Dr Cristina Parau, Department Lecturer in European Politics and Societies at Oxford University, recently edited a special issue of the journal Representation. This issue focuses on the phenomenon of judicial activism in the political sphere. It brings together scholars from different disciplines that hold different perspectives on the judicialisation of politics. It focuses on the contrasts and complementarities of law and politics as modes of democratic representation.

According to Dr Parau, “this special issue seeks to advance our understanding of the judicialisation of politics by bringing together a diverse group of scholars who take different perspectives and apply different methods to investigating the phenomenon and and its impact on representative democracy. The transfer of policy-making power from popularly elected representatives to a judicial elite would seem to weaken democracy in a quite straightforward, zero-sum way, contributing to Europe’s already destabilising democratic deficit. On this account, a renewal of parliamentarism is the only effectual and legitimate cure. On the other hand, ‘representative democracy’ has been criticised since the eighteenth century as elite rather than popular rule; Aristotle classified it as ‘oligarchy’. Representation has defects that might be remedied by judicial intervention. Some scholars have suggested that judicialisation provides a venue for the more active participation of citizens marginalised by the failures of representation; while others even see in judges a form of representativeness with unique properties. The articles in this Special Issue probe these accounts.”

I recently asked her a few questions about the project.

Understanding Neoliberal Legality: Perspectives on the use of law by, for and against the neoliberal project

Neoliberal institutional and economic reforms have attracted substantial scholarly attention in recent decades, but the role of law in the neoliberal story has been relatively neglected. ‘Understanding neoliberal legality’ was the subject of a day-long conference I organised at Oxford in June, which was generously sponsored by the Department of Politics and International Relations. The event drew together 40 established and emerging academics from across the UK and as far away as Canada, Finland, and Australia. These scholars have been independently researching various aspects of the role of law in the construction and contestation of neoliberalism. Many are members of major research networks in political and legal studies, such as the Institute for Global Law and Policy based at Harvard Law School, and edit prominent sites of scholarly discussion such as the debuting London Review of International Law.

The questions and dilemmas animating the meeting included the following:

• What form does law take under neoliberalism and to what extent is this new and different?

• What role do the content and form of law play in shaping the economic, political, and ideological pillars of the neoliberal project?

• What are the implications of these shifts for the ways in which neoliberalism is negotiated and resisted?

Malala’s Visit to Oxford

Pakistan has always been a divided nation—divided between the forces of progression and regression, between secularists and the rest, between those who believe in social equality and those who don’t. Three days before Pakistan gained independence in 1947, Jinnah, the founding father, made clear that religion would have “nothing to do with the business of the state.” Yet, within a year after his death, the Mullahs prevailed. TheObjectives Resolution, passed by the Constituent Assembly in 1949, laid the basis of an Islamic Republic where religiosity has progressed with every passing decade, culminating in its current violent form.

Resistance to religiosity in the country has also been constant. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the first elected prime minister, attempted liberal socialism in the 70s, but had to succumb to the religious right and was finally hanged by an Islamist general. His daughter, Benazir, struggled for progressive politics since the 80s, until her fateful assassination in 2007.

The alternatives are well known. In their attempt to impose Sharia in the past decade, Taliban extremists have silenced thousands of lives. Yet saner voices continue to emerge to champion national struggle against religious bigotry.

Malala Yousafzai, the survivor of Taliban assassination bid last year, is the latest exponent of this just cause. With the late Benazir as her role model, the 16-year-old girl from a rural town says she wants to become the prime minister of Pakistan.

Iain McLean on Constitutionalism, Scottish Secession, and Engagement with Political Theory: Do we need a codified constitution for the (rest of the) United Kingdom?

Iain McLean on Constitutionalism, Scottish Secession, and Engagement with Political Theory: Do we need a codified constitution for the (rest of the) United Kingdom?

Play Episode

Pause Episode

Mute/Unmute Episode

Rewind 10 Seconds

1x

Fast Forward 30 seconds

00:00

/

Subscribe

Share

RSS Feed

Share

Link

Embed

Download file | Play in new windowIn years to come, Saturday 30 November 2013 may be remembered as the last time that a genuinely united Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland came together to celebrate St Andrew’s Day (Scotland’s official national day). With a referendum on Scottish independence set to take place in Scotland on 18 September 2014, the British state’s survival is far from certain. A majority vote in favour of independence would not result in the immediate break-up of the UK (though the Scottish National Party have recently called for full Scottish separation by March 2016 if independence is endorsed at the ballot box). But even so, it is clear that victory for the independence campaign would leave British national unity – terminally battered and bruised – as little more than a wishful façade. If the Great British edifice crumbles to the ground, what are we to make of the pieces that remain?

Identifying the Barriers to Gun Control: lessons from Virginia

For outside observers, gun control seems to be an oxymoron in America. Even following the school shooting in Newtown, the Senate failed to pass an amendment mandating universal background checks on sales of firearms. President Obama reacted with visible anger. He had staked much of his post-election political capital on ‘gun sense’, only to have a watered-down bipartisan bill proposed by two pro-gun Senators muster just 54 votes in the Senate. Polling revealed that the bill had more than 80% support amongst Democrats, Republicans and independent Americans.

The formal American system is famously anti-majoritarian: it is a cluster of staggered, disjointed and (in the case of the Supreme Court) even mythical legitimacies, all of which exercise influence over federal legislation. But questions remain as to why America cannot pass stricter gun laws, when a majority of Americans support a number of increased restrictions.

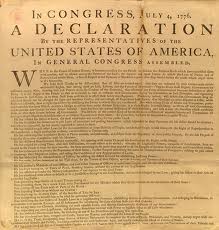

Are we endowed with natural rights?

Are we endowed with Natural Rights from the day we are born? Are these rights conferred to us by God or Nature notwithstanding and beyond any legal rights prevailing at any given time?

Theists may argue that Natural Rights are conferred by Divine power. Theists may sincerely hold that belief. However, both agnostics and atheists may argue otherwise. Theists may be able to argue their case rationally. But so long as Natural Rights bestowed by Divine power cannot be proven empirically, this stance can only constitute a belief in Natural Rights and not an objectively verifiable existence of Natural Rights.

Others may argue that Nature confers on all newly-born individuals Rights that are independent of human-made legally-derived rights. Again, those espousing such a view may sincerely hold that belief. But, as in the case of Devine power-derived- rights, this stance cannot be proven empirically and thus can only represent a belief in Natural Rights rather than an objectively verifiable existence of Natural Rights.

This is not to belittle the enormous power of belief in human affairs; far from it. Belief may be a powerfully motivating force. Thus, a belief in Natural Rights can cause social, political and legal changes; some of these changes may be seen by contemporary protagonists and/or by future generations as historical landmarks.

However, a belief in Natural Rights, notwithstanding their causal effect, cannot by itself be a proof to the effect that these rights actually exist.

The European Commission is wrong about Romania’s Rosia Montana mining project

For the past seven weeks, Romanians have been leading one of the largest environmental protest movements in the world. Around 200,000 Romanians have taken to the streets in cities across Romania and the world to protest against the government’s recent approval of draft legislation for an open-pit cyanide-based mining project at Rosia Montana. According to Gabriel Resources Ltd., the Canadian company behind the scheme, the plan for the project is to dig up an estimated 314 tonnes of gold squirrelled away in Rosia Montana, using 40 tonnes of cyanide per day.

Despite the protests, the European Commission (EC) did not make a statement until only recently. The Commission’s response was prompted when Commissioner Janez Potocnik received a letter soliciting information on the EC’s intended actions regarding Romania’s moves to accelerate the authorization of the mining project, which would use environmentally dangerous cyanide leaching technology.

But a spokesperson representing the Commission emphasized that it was not concerned with the Rosia Montana project because it so far does not breach any EU environmental regulations. The spokesperson added that, as long as the Canadian company obtains its needed licenses, the project would be fine.

The Commission is wrong.