In 2018 Green parties are experiencing unprecedented levels of success in several advanced democracies; however, in a great many others they remain only minor footnotes to national electoral contests. Zack P. Grant argues that variation in Green party support is largely a function of good economic times, the presence of tangible environmental disputes, and mainstream parties actively attempting to emulate the positions of the Greens on their core issues (though the latter is dependent upon the age of Green parties themselves).

Though it has attracted far less academic attention and media fuss than the ongoing ‘rise of the populist right’, several advanced democracies are currently undergoing a pronounced ‘Green surge’. After a somewhat disappointing 2017, in which they suffered parliamentary wipe-out in Austria and lost ground to Jeremy Corbyn’s revitalised Labour Party in the United Kingdom, Green parties are currently polling at an unprecedented 15-20% in Germany (where they place second, comfortably ahead of both the Alternative für Deutschland and the increasingly moribund Social Democrat incumbents) and the Netherlands. Surveys of voters ahead of next years’ general elections in Canada, Australia, Finland, Switzerland and Belgium also make for heady reading, and suggest that support is either equal to or above record levels there too. More concretely, the Global Greens confederation of environmental parties currently boasts of parliamentary representation for members in over 25 countries worldwide. As a collective, the Green party family has come a long way since the birth of the humble New Zealand Values Party at the University of Wellington in 1972.

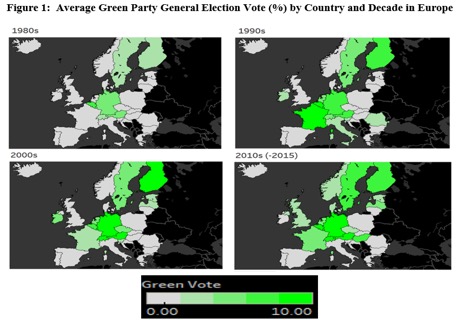

However, the increasing political prominence of the Greens is not distributed equally. Figure 1 displays the marked variation in Green electoral success rates across advanced European democracies from the 1980s to the present. While these parties have gradually expanded out from their West-Central European heartlands, in some countries – for example, the relatively diverse polities of Norway, Spain, and Poland – they remain fundamentally obscure and inconsequential electoral players.

Surprisingly, comparative political science has paid relatively little attention to the contextual predictors of Green party success. Why do these parties – which mobilise around a core subject which (in theory) concerns the well-being and sustainability of every society in the world – perform so unevenly in seemingly similar countries?

Our study

In our recent article, Prof James Tilley and I undertook a quantitative analysis of 347 parliamentary elections from 32 countries (Europe, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia) over the course of 45 years to test competing theories about the causes of Green party success. We used various national-level indicators to model the exact vote share we would expect Green parties to achieve under certain conditions (while holding all others constant at their mean). Our analysis encompassed a wide variety of factors including institutions, socioeconomic development, and mainstream party positions on the environment.

Socioeconomic development and federal institutions

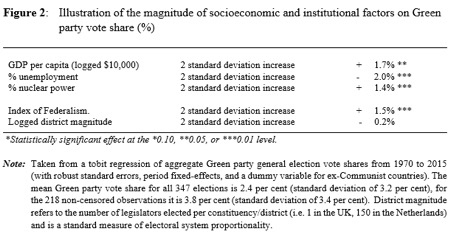

Our findings both confirmed and challenged aspects of conventional wisdom. Greens achieve greater success in wealthier countries characterised by low levels of unemployment. This is consistent with Inglehart’s theory of post-materialism which predicts inevitable shifts in the dominant axis of political conflict from class-based to quality-of-life based issues (of which environmentalism is often treated as quintessential) due to rising levels of existential security. New generations of voters raised in post-scarcity societies are liberated from the traditional political priorities of economic growth and redistribution, and instead become more interested in pursuing ‘higher’ goals. This speaks to individual-level research indicating that Green voters tend to be, primarily, young, highly-educated members of the ‘new middle class’. Furthermore, we find that, all else being equal, the greater the national dependence on nuclear power, the stronger the Greens perform. This indicates that the presence of tangible national environmental disputes can stimulate Green mobilisation. This could be because existing centre-left parties are often forced to compromise on the issue due to the influence of trade unions concerned with protecting industrial jobs. Alternatively, nuclear power could just serve as a major media talking point that has had its salience periodically refreshed by high-profile international incidents from Three Mile Island to Fukushima.

Unlike other studies, however, we do not find evidence to suggest that Greens perform systematically worse under less proportional electoral systems in terms of votes (as reasonably large hauls in Canada, Australia, and France have long indicated) – seat share is of course a separate issue. A more important institutional factor appears to be federalism, which is associated with stronger Green parties, probably as it grants opportunities for small parties to build reputations as credible legislators, which aids future national campaigns. Figure 2 converts each of these variables into standard deviations to indicate the substantive size of these effects.

The role of mainstream parties in Green party success

Another influential idea in the literature is that the policy positions of large mainstream parties are crucial in explaining when minor parties succeed. The Greens benefit from having their key issue discussed by major parties (so the environmental question is not dismissed), and particularly when the major parties take an adversarial stance (the opposite one from the Greens – for example prioritising jobs and economic growth over climate change targets). This simultaneously raises the salience of the issue, granting it greater media attention than if it were just the smaller party alone discussing it, and confers ownership of the ‘pro-environment’ position onto the Greens, meaning that the choice for environmentally-concerned voters becomes streamlined.

Using party manifesto data, we coded the largest two parties at each election as being either dismissive, accommodative, or adversarial towards various ‘green’ issues. Using a similar approach to before, we then examined what effect this had on the Green vote. We found that mainstream parties can reduce the Green vote by behaving ‘accommodatively’ towards Green issues (taking pro-environmental positions); however, this strategy only works when a Green party is relatively new and unestablished. An interaction of mainstream party positions with Green party age (elections contested thus far) revealed that, while mainstream parties can undermine young Green parties by usurping their policies, once the latter have survived three or four contests major party pro-environmental statements tend to benefit the Greens! It seems that mainstream parties find it easier to ‘steal’ a Green party’s market niche (environmentalism) when the Green party is new and lacks the credibility or brand-awareness to monopolise environmental issues. Once that party has survived a few elections (and the public have become more aware of it), further mainstream accommodative strategies simply raise the salience and legitimacy of environmentalism and boost the rival party that (through its very name) can credibly claim to ‘own’ that issue.

Conclusion

While a full analysis of the fate of Green parties would undoubtedly need to make more room for country-specific factors (for example, the apparent role of their uniquely pro-refugee positions in recent second-place finishes in German state elections in Bavaria and Hesse), our article paints a picture of the most ‘fertile soil’ for Green parties. Wealth, good economic times and environmental conflict over nuclear power produces greater numbers of ‘environmental voters’, while decentralisation facilitates mobilisation by creating local springboards for success. Importantly, where mainstream parties do not ignore ‘green issues’ (which is increasingly difficult in light of the ominous recent warnings on the near-future consequences of continued global warming), and have not reacted quickly to snuff out fledgling Green entrepreneurs by ‘greenwashing’ their own image, Greens are well-placed for further success.

This article represents the views of the author, and not those of OxPol. It draws on Grant and Tilley’s recent article, Fertile Soil: Explaining Variation in the Success of Green Parties (West European Politics: 2019).

This article was originally published on Democratic Audit on November, 30th.