The Crisis of Migrant Labour in India during Covid-19

The Indian Government’s initial response to Covid-19—a stringent nationwide lockdown which commenced with an intimation period of only “four hours”—was hailed by the World Health Organisation as “timely and tough.” However, this international acclaim overlooked the disastrous result of the rushed lockdown on India’s migrant workforce. For them, the restrictions imposed by the lockdown has endangered their access to healthcare, housing, food and social security, which has further pushed their lives in precarity. Immediate action is needed from the Central Government to tend to their current needs and provide them with long-term economic stability. Statistics of Migrant Labour in India As per the census of 2011, India has approximately 453.6 million internal migrants. From this, the migrant workforce is estimated to be around 100 million. The Economic Survey of 2017 estimated …

“We might die of hunger before being killed by the virus”: How COVID-19 Compounds the Challenges of Pakistan’s Transgender Community

While the current lockdown in Pakistan has had a detrimental effect on livelihoods across the country, its impact on transgender communities has been particularly devastating. Covid-19 has revealed a troubling picture of transgender people’s social exclusion, marked by high poverty rates, a lack of social security programmes, and structural discrimination. Over the past years, there have been steps in the right direction towards recognizing Pakistan’s transgender community—most notably a 2009 Supreme Court judgement calling for the registration of transgender people as a ‘third gender’ and the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, passed by Parliament in 2018. However, neither measure has been widely enforced. Pakistan needs transformative, equitable policies to ensure equal access to basic public services for its transgender communities, who are currently in a dire situation. Covid-19 provides …

How Natural Resource (Mis-)management in the Nile River Basin May Threaten Stability

As the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) nears completion, the Nile River Basin is at a crossroads. The next few months will be consequential for relations between countries in the river basin—notably Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt—because dam management upstream could have consequences for the supply of water downstream. Although the three countries began discussions after the project was announced in 2011, they have yet to reach an agreement on how the new reservoir should be filled and managed. Despite the absence of an agreement, Ethiopia intends to begin filling the reservoir this July. This article describes the competing perspectives between countries, explains reasons for the lack of an agreement, and provides recommendations for addressing the challenges of the GERD. If …

The Importance of Changing Hukou Status for Better Spatial Equalities in China

From 2016 to 2020, China has been carrying a five-year project of hukou reform, granting urban hukous to rural-to-urban migrants. The hukou system was initiated in 1958 to control the movement of the Chinese population. Each Chinese citizen is assigned either a rural or urban hukou, depending on their residency. It is noteworthy that Chinese citizens cannot hold both a rural and urban hukou simultaneously. This has caused major problems for the estimated 262 million rural workers in urban areas nationwide. The five-year project has sought to convert rural hukous to urban ones to help rural Chinese to succeed in urban areas. As the project comes to an end, it is important to analyse whether hukou conversion – loosening the requirements to change a rural hukou to urban hukou – is conducive to rural Chinese citizens’ educational and social success, …

Is Water a New Flashpoint for Asia’s Rising Giants?

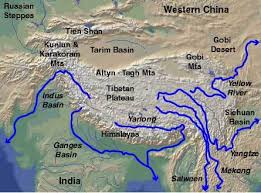

In the past, India and China have disputed numerous issues, from trade to territory. Notably, in 1962, disputes over their Himalayan border regions sparked the brief Sino-Indian War. In the 21st century, a new issue has the potential to become a flashpoint between the world’s most populous nations: their shared rivers.

China has planned, and in some cases begun construction on, major hydropower and water diversion projects in its southern regions, including Tibet, which is making the water security of its downstream neighbors more fragile. The glacial Tibetan Plateau, largely controlled by China, is the source of rivers that supply water to approximately 1.5 billion people. Many of Asia’s major rivers—including the Mekong, Brahmaputra, Yangtze, Yellow, Indus, and Salween Rivers—begin in the Tibetan Plateau, and supply water to people living in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, and mainland Southeast Asia. Thus, China exerts powerful hegemony over Asia’s water resources.

China views the development of rivers originating within its borders as a matter of national sovereignty, not international cooperation. According to one telling Chinese proverb, “Upstream doesn’t suffer.” China does not have river treaties with other nations, making downstream countries vulnerable to water supply disruptions and other environmental damages. In the absence of treaties, downstream nations have no forums for formally resolving water disputes with China, and cannot use international legal institutions to ensure they receive their fair share of water.

A testing and tormenting time for political parties after the 2015 British general election

The ‘sweetest victory’ of the Conservatives, as David Cameron put it on May 8th, and the sweeping landslide victory of the SNP, winning all but three of the Scottish seats, were indeed shocking wake-up calls for all those concerned about British politics. Labour’s unexpectedly disastrous loss of 26 seats led Ed Miliband to announce his immediate resignation as Labour leader. The Lib-Dems were wiped away, going from 57 to just eight seats, causing the resignation of Nick Clegg as party leader. The party was severely punished by voters who blamed it for betraying everything it had stood for in seeking power. Looking at these results, one could argue that the British voters decided at the very last moment to prevent the formation of another coalition government, assumingly returning to their traditional attitude of regarding coalitions as an exception.

For the polling companies too, the election results proved a nightmare. In order to recover their privileged capacity to influence the media, voters, and parties, they are in the course of reexamining why their pre-election forecasts appeared to be inaccurate.

Meanwhile, one shall have a thorough look at how many votes the grassroots parties such as the SNP, UKIP, and the Greens, gained in this election. Even though their positions in the political spectrum span from the left to the extreme right, the total number of votes won by these three parties amounted to nearly 6.5 million, against the Conservatives’ 11.3 million. Amongst them, UKIP failed to get more than one seat and is now in the midst of an internal turmoil. Despite that, Nigel Farage is generally praised for contributing to the party’s net gain from 9.6 to 12.6 per cent of the vote. In particular, UKIP has remained popular among those who are disillusioned with the aloofness of the political elite.

Borders and Barriers: Migration and Economic Exclusion

The search for a better life (sometimes couched in terms of freedom of religion) prompted migration from Europe to the new world in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The ancestors of many North Americans, Australasians and white Africans or South Americans were hailed as pioneers, pilgrims and founding fathers despite the devastating consequences of their arrival on indigenous people. The settlers brought others too: Slaves from Africa or the East Indies, indentured labour from India and voluntary migrants came from the near and far East seeking greener pastures. Global mixing began centuries ago and the world has struggled with multi-culturalism and immigration since. The pursuit of ethnically pure societies is a mirage. The developed countries have multi-generational ethnic minorities from former colonies and everywhere else. Latin America and Africa are dotted with diaspora from the West and the East as well as mestizo groups. Migration continues unabated by borders and exploded on our television screens recently because of two catastrophic events: The sinking of a dingy in the Mediterranean which killed over 900 migrants and a second wave of xenophobic violence in South Africa which resulted in murder, looting and the expulsion of “foreigners” from their homes. Ironically, these events are the consequence of European state centred policy to cut back on rescue missions and anarchic but contagious violence in South Africa, where the state appears complicit by its impotence (until very recently when the army was deployed to protect foreigners).

Poor African migrants have two choices: Head north to Europe or south to South Africa, the largest economy on the continent. Both the governments of Europe and the poor citizens of South Africa cynically believe that danger will deter immigration. People will think twice about crossing the Mediterranean if the risks of drowning or deportation are great enough. Similarly, Mozambicans and Zimbabweans will leave South Africa and others will stop coming if the probability of being killed or dispossessed is greater. “They” need to get the message that “we” don’t want them, we have too many pressures coping with our own problems. Right wing parties in Europe and King Goodwill Zwelethini in South Africa have stoked the flames of intolerance and fear, turning public opinion against migrants so fiercely that the bounds of morality and humanity are being tested. Yet Italy and Greece are overwhelmed and the migrants who have fled South Africa will return when the situation calms down and more will still come. Danger does not deter when desperation is sufficient or when the danger of staying surpasses the danger of leaving. The people who risk everything to come to Europe or South Africa are driven by more than greener pastures; they feel that their survival depends on escape. Some are asylum seekers fleeing from conflict or ethnic cleansing but others are as desperate for work and a future.

Trading Water: Could Markets Be One Solution to California’s Water Woes?

Drought-stricken California is taking unprecedented measures to address its water challenges.

In April, the governor issued the first mandatory statewide water use restrictions in California history, after snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountains—which provide 60 percent of the state’s water—fell to the lowest levels ever recorded. San Diego County is building the largest seawater desalination plant in the Western hemisphere, while Orange County plans to turn more wastewater into drinking water.

The solutions are significant because the drought has been exceptionally severe. It currently affects over 99 percent of the state and approximately 37 million people. In 2014, the state agriculture industry lost roughly $2.2 billion to drought, and some California communities even ran out of water.

One solution California may consider is whether more efficient, user-friendly water markets would help water users adapt more quickly to drought conditions, and better cope with long-term water scarcity stemming from climate change and increased water demand.

California has active water markets, but buying and selling water (and water rights) there is not as simple as in Australia, where it is said to be “almost as easy to sell water from your water bank account as it is to transfer money from a normal bank account.” The Australian model could be useful for California because Australia recently emerged from a decade-long drought, during which it pioneered water policies that attracted interest from water-scarce countries around the world.

Why is water trading easier in Australia? One reason is that Australia’s water rights system has been made relatively simple and predictable. It is designed so that rights holders can generally expect to receive a certain percentage of their water every year, based on the type of water right they hold. This makes water rights’ value easier to determine; the water rights transfer process is also less onerous.