Almost a week after Hamas launched a surprise attack on Israel on October 7, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, called for a global peace conference and a ceasefire. China’s messages can be boiled down to three main points: 1) condemning attacks on both Israeli and Palestinian civilians and the breaking of international law, 2) calling for dialogue between the warring sides, and 3) emphasising the necessity of a two-state solution. China’s messaging follows a similar pattern expressed after previous Israel-Palestine escalations, whereby Beijing refuses to take sides explicitly, urging restraint and promoting peace talks.

Chinese-Palestinian & Chinese-Israeli relations:

China’s ‘neutrality’ leans in support of Palestine, at least rhetorically. While insisting on both Israel and Palestine’s right to statehood, Wang Yi called out Israel for going beyond “the scope of self-defence,” stating that Palestine has been subject to injustices “for over half a century.” China has officially recognised Palestine as a state since 1988 and has maintained friendly relations by providing both diplomatic and economic assistance. Beijing neither designates Hamas nor Hezbollah as terrorist organisations. Moreover, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas has visited China on multiple occasions and signed a strategic partnership agreement with Chinese President Xi Jinping in June 2023.

Despite these shows of support, China has maintained a flexible diplomatic approach within the region. Under Mao, China supported national liberation movements and branded Israel as a part of Western imperial agendas. However, in 1992, Beijing officially established diplomatic ties with Tel Aviv and has since committed to a more diplomatically nuanced stance. Similar to China’s approach to Japan, it pursues a ‘cold politics, hot economic’ (政冷经热) approach vis-à-vis Israel, whereby China deepens its economic ties with Israel despite disagreeing with its geopolitical objectives. While not officially a part of China’s Belt and Road initiative, Israel is among the region’s top-ranking receivers of Chinese investments. Beijing also consistently imports high-tech products from Israel. The United States has been at least partially alarmed by these deepening ties, going so far as to warn Israel to reduce cooperation with China.

What’s in it for China?

China’s ‘neutrality’ serves both material and non-material objectives. As evidenced by its approach to Israel and Palestine, instead of adopting a region-wide foreign policy approach, Beijing has established different bilateral strategic partnerships with several Middle Eastern states, granting China significant diplomatic flexibility. Unlike traditional alliances, which demand official commitments and lower levels of flexibility, strategic partnerships are low-risk and prioritise common interests in various areas rather than military commitments. Using this approach, China avoids directly challenging US interests in the region and angering any specific Middle Eastern state. It is worth noting that China has invested in the overall stability of the region despite not having explicit multilateral or region-wide goals. The Belt and Road Initiative, along with similar Chinese investments, require the region to be relatively stable. Furthermore, China sources around half of its oil from the Persian Gulf. These material concerns could partially explain China’s growing interest in regional affairs.

Beyond material concerns, China has a growing interest in being perceived as an alternative ally for those dissatisfied with the US-led international order. Earlier this year, Beijing hosted talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia and successfully brokered an agreement to reestablish diplomatic relations between the Middle Eastern countries. Experts suggest that this not only reflects China’s growing international relevance, but also regional actors’ changing perception of how China could potentially displace the US as the region’s most relevant superpower. China’s interest in being a mediator and pro-Palestine ‘neutrality’ have enabled Beijing to set itself apart from the West. It presents China as a leader for the Global South countries, many of which are sympathetic towards Palestine’s situation and have criticised the US for being hypocritical about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Beyond wishing to be seen as a responsible power, Beijing seeks to be regarded as an empathetic power that understands the challenges confronting developing states. This ambition is reflected in China’s Global Security Initiative (GSI), launched in April 2022 and followed by a ‘concept paper’ in February 2023. GSI is presented as a Chinese solution to global conflicts, offering a security architecture that differs from the US vision of the global order. The GSI echoes other principles that China consistently champions, including “sovereign equality and non-interference in internal affairs,” specifically mentioning equality under international law regardless of a state’s size or income level. These are attempts of signaling China’s opposition to Western hegemony, suggesting that Beijing can empathise better with the political and security needs of Global South states.

Limitations or Intentional Grandstanding?

Critics of China’s security initiative argue that, as it currently stands, GSI is non-specified and simply re-packages old security concepts. GSI’s deliberate vagueness could be interpreted as political grandstanding. This is particularly evident in China’s approach to the Middle East, as many doubt the extent of Beijing’s ability to effectively mediate in the region. Other than a lack of extensive regional experience and expertise, one thing experts question is China’s willingness to accept the risks associated with the follow-through on mediation. While the Saudi-Iran deal reached in Beijing was commendable, its eventual success resulted from a series of long-term talks and efforts hosted by an array of countries, rather than Chinese mediation alone. This raises the question: what does China mean by ‘mediation’? Perhaps it is more appropriate to describe Beijing as a facilitator rather than a mediator.

Like GSI, China’s proposed plans for regional peace have largely been rhetorical, lacking in practical follow-through and step-by-step action plans. Beijing’s first Five-Point Proposal on Israel-Palestine was established in 2003. Since then, many similar proposals have been put forward without substantial efforts to implement them in practice. Although this could be due to China’s inability to provide incentives to the warring parties to resolve a protracted conflict, it could also represent an act of intentional grandstanding. Much like its carefully maintained neutrality, grand gestures provide China with political brownie points while allowing it to minimize risks and maintain diplomatic flexibility. Israel-Palestine may thus be seen to offer China a political theatre where it can condemn Western powers for being irresponsible, while offering idealistic deals which no party has the incentives to implement.

It remains to be determined whether China can maintain its ‘neutrality’ if regional tensions continue to rise. Beijing’s balancing act has put a dent in its relationship with Tel Aviv, with Israel’s foreign minister responding to China’s lack of “clear and unequivocal condemnation” of the Hamas attack with “deep disappointment”. Nevertheless, Israel’s economic ties with Beijing have yet to be significantly impacted.

What we know for certain is this: the United States’ close geopolitical ties and support for Israel often make it the sole great power relevant to the mainstream discussion of the Israel-Palestine conflict. However, in recent years, China’s increasing interest in Middle Eastern affairs and growing ties with regional powers have made its position in the conflict worth understanding. While criticisms of China’s limited ability to provide incentives for regional powers may very well be true, it is essential to recognise how China’s current neutrality and grandstanding serve their purposes.

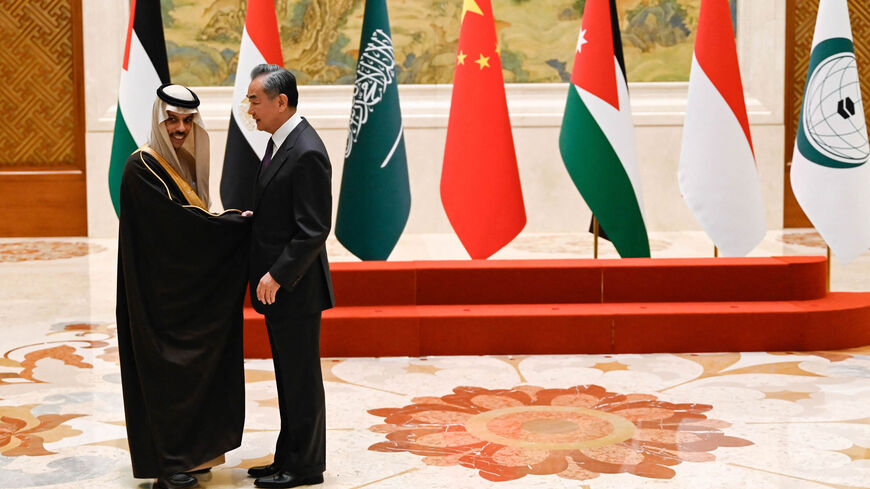

Displacing the US as the most relevant great power in the region poses risks that Beijing is unwilling to take for now, but image-building China into an empathetic great power can yield more immediate benefits. Just this week, officials from Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, the Palestinian National Authority, Indonesia and the head of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation came to Beijing for a two-day visit. China’s legitimacy as a relevant regional player is unarguably increasing, with or without concrete diplomatic outcomes. Presenting alternative security approaches also attracts attention to China’s multilateral institutions and forums, such as Shanghai Cooperation Organizations, BRI, and China-Africa Peace and Security Forum. Ultimately, China’s approach in the Middle East reflects Beijing’s larger ambitions on the world stage.