YouTube is a prime space for the communication of the hundreds, if not thousands, protests that have taken place around the world since mandatory measures were introduced by governments to contain the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. From New York to Tokyo and from London to Sydney, protesting social distancing, face coverings, lockdowns and vaccines is caught up in hours of video footage by protesters themselves, passersby, and reporters, featuring as content for the YouTube channels of major international news agencies. According to a recent publication in Harvard’s Misinformation Review, such videos often serve as a backdrop for commentary out which emerge “participatory cultures of conspiracy theory knowledge production and circulation”. Here, I would like to shed light on a related yet much broader role of YouTube videos of Covid-19 protests. Their role in arresting on-screen, instead of feeding into comments about, a “lived experience of injustice”: the pain inflicted by riot police, the mass damage caused by protesters, and the self-righteous indignation voiced by them, among others. Feelings of injustice are platformed-staged/performed, through YouTube videos, to confront viewers with a sense of belonging to a victimized people: this is what I call platform spectacle of populism.

The platform spectacle differs from the Society of the Spectacle as envisaged by French philosopher Guy Debord more than half-a-century ago. Spectacles are no longer exclusively produced by mass media institutions to be consumed by their national audiences but can be both produced and consumed on and through social media platforms by their locally, nationally and/or internationally networked publics. The platform spectacle is not just about journalists, politicians, and other actors with privileged access to mass-mediated visibility, speaking in the name of a national/social community. It is also, increasingly, about multiple, professional, and amateur content creators competing for social-mediated visibility through performing their own everyday life as part of nationalist communities (e.g., #AmericaFirst), as well as feminist (e.g., #MeToo), black-activist (e.g., #BLM) and various other communities. Debord’s critical insight into spectacle as a media performance that is shaped by capitalist instrumental logics is still relevant, though, especially in understanding how and why the communities imagined through platform spectacles are often, particularly, imagined as communities of victims.

Being recognized as “the victim” is not only a status of moral superiority for someone, enshrined in the social imaginaries of Western morality since the Holocaust, but also a source of politico-economic profit for themselves or others. The online market of “#MeToo merchandise, ranging from #MeToo cookies to jewelry to clothing”, for instance, and Amazon using the #BLM banner on its home page and prime videos are just a few typical examples of an economy of visibility that thrives on the commodification of victimhood. YouTube videos of Covid-19 protests come to redeem the value accrued to the victim status in rather ambivalent ways. On the one hand, videos draw attention to the loud minorities of protesters self-performed as victims of pandemic biopolitics. Based on this, lockdowns and vaccines are insidious mechanisms designed by governments and implemented by the police to take total control over people’s lives and human existence (as it is shown, for instance, in the banners captured in the screenshots below).

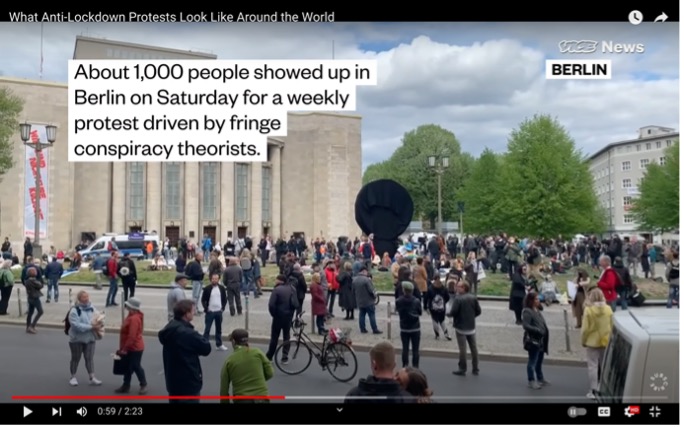

On the other hand, YouTube videos of Covid-19 protests also appeal to a silent majority of “us”, counter-performed as victims of pandemic reactionism. Now protesters are “othered” for taking advantage of the great uncertainty surrounding restrictions and vaccines to promote their far-right/left, conspiracist, or other extremist agendas (as the video captions verbalize and the peculiar accessory choices visualise in the screenshots below).

Both pandemic biopolitics and pandemic reactionism are guided not by the structural social conditions of the injustices they claim to attend to (e.g., class, gender or race) but by the tactical positions of power from which the claims to injustice are made. The self-victimizing claims to pandemic biopolitics, for instance, are made by actors at the “periphery” of digital media production (mostly protesters themselves), who camera-capture on-the-ground the radical precarity of protesting and/or giving testimonies over which they have no further control. These actors struggle to amplify their visibility as an insurgent political subject by capitalizing on controversial minority victimhoods that are possible to fly well with YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, as relevant to radical publics still suspicious of the Covid-19 health emergency. On the contrary, the other-victimizing claims to pandemic reactionism are made by actors at the “core” of digital media production (editors or channel administrators), who platform-accustom testimonial footage from the safety of post/production spaces. These actors seek to optimize the platform metrics of their organizations by investing, instead, on majority victimhoods that are expected to win over the algorithm based not as much on their targeted relevance as on their overall popularity.

Concluding, I wish to argue that the YouTube spectacle of Covid-19 protests not only does it confront us with a sense of belonging to the people-as-victim but also plays into a politics of belonging that establishes hierarchies regarding who is (un)worthy of attention as and, therefore, a place in the people-as-victim. In line with conventional right/left-wing populism, the politics of belonging may call into being a reactionary or radical people as victim of the liberal capitalist establishment. But it may also, reversely, call into being a decent-moderate liberal people as victim of the radical or reactionary anti-establishment extremes, in a move known as “centrist populism”. Even though this performative variation of the politics of belonging reflects the ideological ambivalence of populist victimization in the platform spectacle of protesting, the ethico-political question of who is worthy of a place in the people is not, in fact, left with multiple answers: it is the high-profile victims that content-makers and platform-owners deem to be algorithmically recognizable. Quite the contrary, the low-profile individuals and groups that are subject to systemic vulnerability, such as those at high health-risk because of the pandemic, without suffering in a spectacular manner that would “move” our algorithmic norms of attention-worthiness, remain non-victimized and, thus, unseen and unheard.