The theory of incommensurability presents us with the view that when forced to decide between different options, we may lack the ability to objectively compare the values underlying each alternative. Though our ultimate decision may be grounded in a variety of reasons, the fact of our decision is not proof in itself that the values behind our choice are better than those that we left behind. Some principles may rise above others, according to incommensurabilists, but that means only that they have won the battle in praxis, not in ethics.

The impossibility of comparison may exist in some cases, but incommensurability fails to justify the ethics behind the ranking of values in policy matters; without compromise, the valuation of equal human welfare ought to be the chief concern in politics. Whenever the pursuit of other interests trumps support for popular wellbeing, it is never entirely the case that two options could not be commonly evaluated, and to say that they are incommensurable is to cloak the deliberate de-prioritization of human interests for another end. Tangential to the notion of incommensurability is a more complex, and perhaps more pressing aspect of political and ethical life. Just as incommensurabilists struggle to come to terms with the existence of competing values, of even greater concern is the problem of incompatible ideologies: mutually-exclusive belief structures that give meaning and weight to values.

Incommensurabilists are right to worry about the forced comparison of conflicting values, but misdiagnose the dilemma. When politicians choose to respond to economic incentives at the expense of the wellbeing of citizens, surely there is a disconnect. As James Griffin underscores, “It is a fact of life that some values, by their nature, exclude others…[and] our choices can leave us with an uncompensated loss.” Griffin’s point elucidates that, when a choice demonstrates preference for something other than human life, it is not simply a case of incommensurable alternatives, but that something deeper is at play.

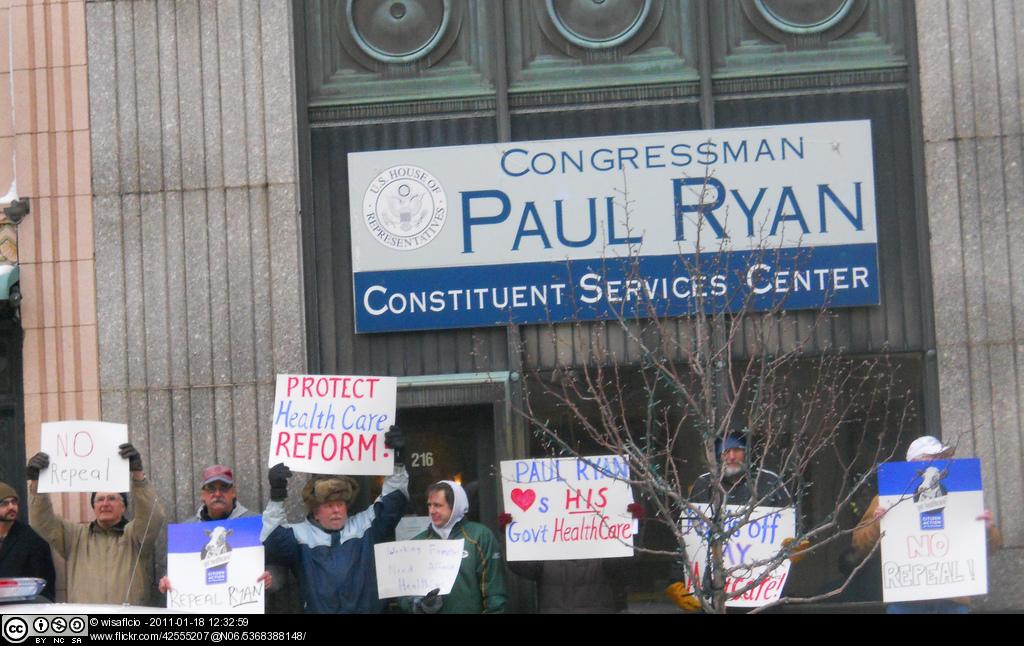

The recent budget proposal by U.S. Representative Paul Ryan, for example, which claims to stimulate economic growth by removing funds from the recently passed public health option , suggests that conflicting values are evidence of incompatible ideologies. Unabashedly considering human interests in financial terms, Joseph Raz discusses the Marxist critique that the rise of capitalism had “resolved personal worth into exchange value.” A decent description of American conservatism, this recalibration of human welfare on par with market forces “treats as sacred the equal right of individuals to reap whatever rewards accrue from whatever they own.” By contrast is the liberal egalitarian conviction in the sanctity of human welfare, as represented by the state’s provision of health, education, and a minimum standard of living. The tension between these two views, emblematic of the polarization of contemporary American politics, is that while the former sees social goods and access to them in terms of dessert and relative privilege, the latter conceives them as an inalienable right. Following Griffin, it seems that the values underlying these distinct ideologies cannot both be realized together.

Despite their antimony, these perspectives do not escape comparison; they are not incommensurable, but rather incompatible. American conservatism and liberal egalitarianism are belief structures that entail a ranking of values, many of which are part of a shared ethical vocabulary. The crux of the matter is that each system accords these values almost reverse importance, recalling the incommensurabilist concern over goods having different statuses or occupying unique roles in deliberation. For Conservatives, autonomy of property seems to be regarded most highly, while liberals defend as most urgent the equality of attainment of basic rights. This contrast in priorities stems from irreconcilable conceptions of what constitutes the good life. Conservatives are committed to the view that eudemonia is only available on a you-merit-what-you-earn-basis, that this may or may not include the State, and if so, in a limited capacity chiefly involving the security of private goods. Liberals, on the other hand, believe that the good life ought to be accessible to everyone, and that the State ought to provide certain services, such as health care and education, in order to make such a life possible. With their opposite ordering of priorities, American conservative and liberal ideologies are constituted by “partial values.” The problem is that, no matter what attempts are made at bipartisanship, these beliefs systems are incompatible at their core, for they are “…exclusive to particular relationships, practices, or ways of life, and what makes them valuable is their contribution to the survival or flourishing of these.”

What is so fascinating about the Ryan budget proposal is how its threat to remove programs such as Medicare in order to lower the corporate tax rate by 10% has awakened impassioned protests from middle-class and lower-income conservatives who realize that the adoption of this plan would quite literally end their way of life as they know it. It appears that these traditionally conservative voters, made vulnerable by the recent financial recession, are beginning to rethink the structure of values endorsed by party politics, whose policies seem to communicate that profits, not people’s welfare, are the bottom line. Now, beyond the inevitable conflict between liberal and conservative ideologies, tensions have emerged within the conservative base that reveal the “separateness and irreducibility of the standing concerns that make up our orientation toward distinct values and commitments.”

The preface to Congressman Ryan’s budget plan communicates a surprising truth: “Ultimately, a budget is much more than a series of numbers. It also serves as an expression of Congress’s principles, vision and philosophy of governing.” Though the constitutional mandate of American government is to be impartial, “…commitment to [impartiality] requires the acceptance of principles that favour no particular relationship.” Nevertheless, “…attempts by public bodies to reconcile competing obligations in the face of finite resources” results in either trade-offs, or sacrifices. Unlike the vertical positioning of ranked values, a trade-off implies that goods are of commensurate value, on a horizontal plane. The reality of American politics, dominated by partial values, instead demands sacrifice: the assent of one set of principles cancels out the other.

In contrast to the incommensurabilist aversion to the comparison of chafing values, of more compelling concern is how clearly we can measure particularly incompatible belief structures up against one another to reveal a reverse ordering of principles. The fact that two ideologies cannot pursue their ends simultaneously does not mean they cannot be evaluated side by side; as concerned, ethically minded citizens, we ought to demand a transparent comparison of both liberal and conservative value systems. Within these incompatible ideologies, to make the incommensurabilist claim that one or more goods—such as economic incentive and human welfare— are so different from one another that they cannot be viewed in the same light, allocates an almost untouchable place for some positions that ought to be morally outweighed by others.

Cailin Crockett is a first-year MPhil in Political Theory at Oxford University and Graduate Ambassdor for PoliticsinSpires.org; her research is on gender policy and global justice

1 Comment

I was recently at the peace Journalism conference at St John’s College and saw a presentation by a Reuters journalist (the podcast of this should be available soon).

The journalist was discussing how Nagaland was “underreported” when compared to the Kashmir – even though more people had died in the associated troubles in Nagaland. The journalist presented a series of stats (alongside those killed), but deep down I think there was an argument that SI of newsworthiness.

My mind thought that the SI unit of news is perhaps a wild goose chase (only a ‘perhaps’) but a modern state should be able to assess or present the statistical potential impact of a new law.

Obviously the UK is not a constitutional democracy, but it’s a curious thought (constitutionally) that only laws benefiting 50% of the public could be passed.

It’s almost unworkable even in my mind, but my first thought was it might refocus bill making from issues primarily round those of taxation, on to perhaps those of “bigger politics”.