In the past, India and China have disputed numerous issues, from trade to territory. Notably, in 1962, disputes over their Himalayan border regions sparked the brief Sino-Indian War. In the 21st century, a new issue has the potential to become a flashpoint between the world’s most populous nations: their shared rivers.

In the past, India and China have disputed numerous issues, from trade to territory. Notably, in 1962, disputes over their Himalayan border regions sparked the brief Sino-Indian War. In the 21st century, a new issue has the potential to become a flashpoint between the world’s most populous nations: their shared rivers.

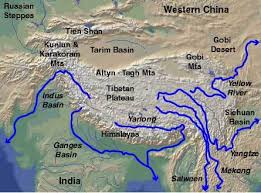

China has planned, and in some cases begun construction on, major hydropower and water diversion projects in its southern regions, including Tibet, which is making the water security of its downstream neighbors more fragile. The glacial Tibetan Plateau, largely controlled by China, is the source of rivers that supply water to approximately 1.5 billion people. Many of Asia’s major rivers—including the Mekong, Brahmaputra, Yangtze, Yellow, Indus, and Salween Rivers—begin in the Tibetan Plateau, and supply water to people living in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal, and mainland Southeast Asia. Thus, China exerts powerful hegemony over Asia’s water resources.

China views the development of rivers originating within its borders as a matter of national sovereignty, not international cooperation. According to one telling Chinese proverb, “Upstream doesn’t suffer.” China does not have river treaties with other nations, making downstream countries vulnerable to water supply disruptions and other environmental damages. In the absence of treaties, downstream nations have no forums for formally resolving water disputes with China, and cannot use international legal institutions to ensure they receive their fair share of water.

Many nations other than India have experienced negative environmental impacts as a result of Chinese dam development—including the Southeast Asian nations on the Mekong River, Kazakhstan, and Bangladesh. India, however, is the only affected country in the region that has comparable levels of economic and political power to China. If any Asian country can persuade China to adopt river treaties or at least a more equitable approach to river management, it is likely to be India. However, China’s current domestic river development policies—which include major hydroelectric dams and a nationwide, south-to-north water diversion project—indicate this will not be easy.

Nevertheless, India has major incentives for pushing for river accords with China. India is one of the most water-challenged countries in the world, with 17 percent of the world’s population but only 4 percent of global water resources. Groundwater mining and severe pollution have diminished usable water supplies. Water shortages have closed Coca-Cola plants in India, and a 2012 drought reduced India’s GDP by 0.5 percent.

By 2050, India is predicted to become a water-scarce country, at which point freshwater availability would fall below 1,000 cubic meters per person per year, and would begin to hamper economic development, public health, and general human well-being.

This is a precarious situation not only for India, but also for China. The Chinese workforce is aging, and the consumer demand in China’s middle class is growing. Neighboring India, with a younger workforce and fast-growing economy, is ideally situated to meet that demand. Recognizing this, China has offered to invest billions in Indian infrastructure and has moderated government rhetoric on contentious Sino-Indian issues, including border disputes. However, rising water scarcity—made worse by climate change—could impact the Indian manufacturing sector’s future ability to meet Chinese consumer demand. Thus, China has an interest in ensuring that India remains a water-secure country, although China’s current major hydro-engineering projects demonstrate that the Chinese government is focused, first and foremost, on addressing China’s own serious water scarcity challenges.

Finally, there remains the (slim) possibility that Sino-Indian water disputes could become conflicts. Water security analysts generally believe it is unlikely that China and India would actually go to war over water, as the countries see themselves as responsible powers and the economic, political, and reputational costs to both nations would be high. Furthermore, water disputes tend to be resolved through cooperation rather than conflict. Cooperative events between countries that share rivers were found to outnumber conflict events by more than 2:1 from 1945 to 2008. Nevertheless, in view of their historically rocky political relations and the absence of Sino-Indian river-sharing treaties, river relations between China and India—particularly on the major Brahmaputra River—remain a focus for conflict and security analysts, as conflict could arise if their political relations deteriorate.