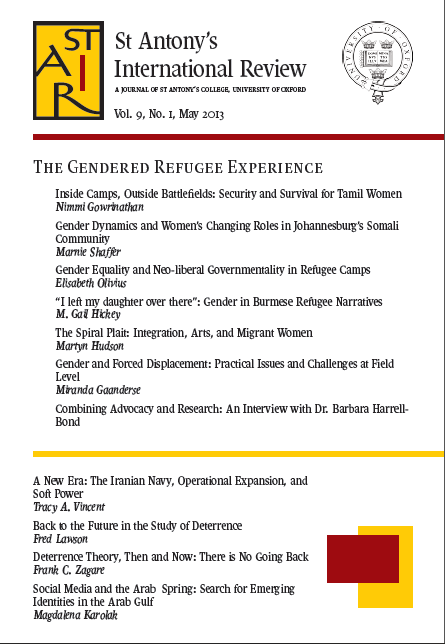

‘I do not believe that gender equals women—a fact that has been neglected,’ says Dr. Barbara Harrell Bond, in an interview found in the newest publication of the St Antony’s International Review (STAIR), entitled “The Gendered Refugee Experience”. Set to launch on 23 May at 17:00 in Queen Elizabeth House the issue addresses gender as a dimension in claims for asylum and, more centrally, as a central component in post-flight experiences. More details about the launch can be found here.

‘I do not believe that gender equals women—a fact that has been neglected,’ says Dr. Barbara Harrell Bond, in an interview found in the newest publication of the St Antony’s International Review (STAIR), entitled “The Gendered Refugee Experience”. Set to launch on 23 May at 17:00 in Queen Elizabeth House the issue addresses gender as a dimension in claims for asylum and, more centrally, as a central component in post-flight experiences. More details about the launch can be found here.

Gender is not a new topic in refugee studies, and gender is increasingly used as a word that is not merely interchangeable with ‘women’. Since the 1980s, individuals persecuted for their gender-identity have had access to asylum – albeit rarely – and both men and women can be victims of rape and victims of Sexual and Gender-based Violence (SGBV). Gender is a factor, not simply a description of half the world’s population.

Gender is important not only because the treatment of women and men is often different or perceived as different, but because the choices that men and women make, and the persecution they face, is often different than we expect based on our stereotypes of what men and women are like. Some stereotypes we easily reject, as they seem obvious; it is not particularly original to state that women are in the workforce and men are also victims of rape. Yet, some are less obvious. This issue of STAIR addresses stereotypes we have regarding gender that we are often not aware of which can impact the type of research conducted among victims of forced migration.

For example, there has been little research on women who become combatants in response to SGBV. Nimmi Gowrinathan, in her article entitled ‘Inside Camps, Outside Battlefields: Security and Survival for Tamil Women,’ focuses on female combatants of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Gowrinathan shows how gender-based violence can be a form of state repression and, in this case, lead to responses of political resistance in the form of joining the LTTE. Today, ‘without the umbrella of an established insurgent movement, the risks for women’s political activism are higher than they have ever been.’ Her innovative work is not only about women, but about how some individuals, as people, respond to sexual violence.

Seemingly less dramatic than joining a resistance movement is joining the workforce, yet the attitudes of women in the workforce, and the risks they face as refugees in a host country, are often overlooked. In current academic and NGO literature, economic participation and access are often viewed as a form of empowerment for women, and greater respect within the household. In Marnie Shaffer’s piece, entitled ‘Gender Dynamics and Women’s Changing Roles in Johannesburg’s Somali Community,’ women interviewed by the author insist that their choice to work is not for empowerment, but for necessity when their husbands cannot work. In contrast, some men Shaffer interviewed insist that women work in order to undermine the role of the male as head of household. Ultimately, the reason women insist that their employment is purely instrumental may be because women are still dependent on their communities for basic security in light of xenophobic attacks. Paradoxically, their dependence on their wider community for general security means they cannot turn to the South African police when members of their own community commit acts of SGBV against them. Women insist that working is not to undermine dependency on the men in their family precisely because they are still dependent on these men.

If the Somali women in Shaffer’s piece view working as instrumental, so does the neoliberal governmentality agenda, according to Elisabeth Olivius, who examines humanitarian aid workers in refugee camps in Thailand and Bangladesh. Her article, entitled ‘Gender Equality and Neo-liberal Governmentality in Refugee Camps’, shows that the focus on measurable outputs often ignores problematic underlying power relations. For example, when girls drop out because they are pregnant, but boys drop out because of drug addictions or to work, near-identical dropout rates can mask disparate opportunities.

Shaffer’s work, which presents how women can be forced to remain within their communities, compliments the article by Martyn Hudson, who presents an analysis of ethnic enclaves among refugee women in the United Kingdom in his article entitled, ‘The Spiral Plait: Integration, Arts and Migrant Women.’ Like with Shaffer’s work, he shows that deep involvement in local community structures can be less than voluntary. Social isolation, writes Hudson, combined with dependency on local social structures, may further prevent integration within the wider society.

Gail Hickey, in this latest issue of STAIR, also discusses familial community networks in ‘“I left my daughter over there”: Gender in Burmese Refugee Narratives.’ For Hickey’s respondents, though the loss of security from familial networks upon fleeing Burma was cited as a factor in the loss of security, the central factor was the failure of the Thai government to protect refugees in and outside of camps.

Like Olivius, Hickey also addresses SGBV as a form of state violence. Rape of both males and females of all ages by Thai police and soldiers, severe and violent interrogations, and a lack of medical treatment were common and interviewees recall their fear of being separated from their families and communities and forced into prostitution by Thai authorities.

Clearly, ‘gender’ is not interchangeable with ‘women.’ Yet, gender may be central to better understanding why women, and specifically women, make particular choices. At the same time, women may make particular choices in one context for reasons that are similar the choices men make in other contexts. Studying why some women become combatants after being victims of SGBV may be invaluable in generating theories as to why victims of SGBV more generally choose to take up arms. Research on female combatants may be especially helpful in contributing theories for further empirical inquiry into the choices male rape victims make, including possible relationships between male SGBV victims and men who choose to join combatant groups. Similarly, understanding why some women insist they are only working because their husbands cannot, rather than for self-empowerment, may help us understand general experiences of those seeking employment after fleeing. After all, both men and women may not view low-paying labor, in the face of xenophobic attacks and little protection from the government, as especially empowering. Similarly, understanding why some women remain within an ethnic enclave or community can raise theories that are generalizible and applicable to both men and women, who may face different forms of social isolation, but similar impacts from social isolation. If the reasons women face certain challenges are almost never found amongst men – such as pregnancy leading to one dropping out of the school in a refugee camp – these differences can still generate a better understanding of the relations between men and women’s experiences.

Adding gender to the equation in a way that places greater emphasis on women need not sidestep the experiences men, nor overshadow the important research into LGBT-related persecution. The articles in this issue of STAIR therefore move beyond ‘gender’ as ‘women’ even as they focus on women. In doing so, they provide new, innovate theories that can shed light on our understanding of refugees, Internally Displaced Persons, and asylum more generally.

The issue “The Gendered Refugee Experience” will be sold at the launch event. It is also available at Blackwell’s on Broad Street and online.

1 Comment