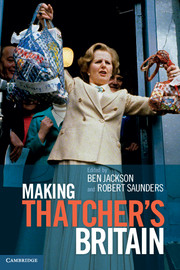

Robert Saunders is co-editor (together with Ben Jackson) of Making Thatcher’s Britain. He teaches History at Jesus College, Oxford, and Politics at Lincoln College.

I really enjoyed Making Thatcher’s Britain. Can I start by asking a biographical question about Thatcher before we get to the book — how did she come to lead her party in 1975? Was it a result of a careful campaign or happenstance?

I really enjoyed Making Thatcher’s Britain. Can I start by asking a biographical question about Thatcher before we get to the book — how did she come to lead her party in 1975? Was it a result of a careful campaign or happenstance?

There was a degree of good fortune to the affair. If Ted Heath had resigned a year earlier, or if Keith Joseph had run in 1975, Thatcher would not have been a candidate. She won partly because of a brilliant campaign organisation, and partly because she was the only one willing to challenge such a dominant leader. But it was no coincidence that the challenge came from the right of the party. The economic and political failures of the 70s encouraged a perception, in both parties, that the policies of the post-war era had run their course. There was a greater willingness to pursue radical alternatives, and Thatcher offered a clarity of vision that many found attractive. Bismarck once said that the statesman must ‘listen for the footsteps of God, then grasp the hem of his garment’. That’s what Margaret Thatcher did in 1975.

Your introduction to the book is about ‘Thatcherism’. Do you find that term useful?

Yes – so long as we don’t try to impose on it a single definition. This is a word that was coined by the Labour Party, theorised by Marxist academics and worn as a badge by an extraordinary range of people. For some, it was a personality cult or a style of leadership; for others, an approach to monetary policy or a view of Britain’s place in the world. It allowed people who did not think of themselves as ‘Conservative’ to align themselves behind a Conservative government, and it would provide a stick with which to beat John Major and his successors. Thatcherism is a discourse to be interrogated, not a simple, analytical tool.

But it does capture something important about Mrs Thatcher, which is her faith in the power of ideas. More than any of her predecessors, she used the premiership as a pulpit, from which to preach her values to the public. She talked of ‘the ideological battle against socialism’, and sought to use her position to change the national mindset. As she told the Sunday Times: ‘Economics are the method: the object is to change the heart and soul’.

You also have a chapter about the ‘think-tank archipelago’, and the names of Thatcher advisors trip off the tongue: Walters, Joseph, Whitelaw. To what extent was Thatcher herself responsible for the policies she has come to be associated with?

A lot of the detail came from elsewhere. Think tanks did much of the technical work, while the Conservative Research Department and even the Civil Service deserve more credit than they usually receive. It’s also hard to overstate the role of senior ministers. Much of what we think of as ‘Thatcherism’ was actually pushed through by Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson – sometimes against Thatcher’s own instincts.

What Thatcher provided was a sense of direction, a set of values against which such policies could be tested. If a policy met that test, and if she thought it could be done politically, she would support her ministers and put her authority behind the idea.

The dedication in Making Thatcher’s Britain is to Ewen Green who is well known for drawing parallels between Conservatives. Does your book back this view or the colloquial view that Thatcher was a one off?

Early commentators on Thatcherism tended to stress its novelty. For the Marxist left, this was a sign that capitalism was moving into a new (and possibly terminal) phase. For Thatcher’s Conservative critics, it allowed them to position themselves as the authentic voice of party tradition. And there’s no doubt that Thatcherism drew on influences from outside her own party: from American neo-liberalism to her own provincial non-conformity.

But there was nothing very unusual about this. As a political party, rather than a cult, Conservatism has always drawn on other intellectual traditions. From Benjamin Disraeli to Winston Churchill, some of its most famous leaders have come from outside the Conservative tradition; and it has always been an eclectic mix of free traders, protectionists, little Englanders and global traders. Most of what Thatcher did had some precedent in Conservative politics: from the working class Toryism of the high Victorian age to the anti-socialism of the interwar period. Her willingness to tolerate the welfare state, while waging war on socialist economics, would have been entirely familiar to the party of Churchill and Eden.

Conservatism is organic, and no one government is wholly like another. Thatcher used different policy tools to her predecessors, but her governments grew recognisably out of a prior political tradition.

Lots of the outpouring of feeling since Monday has centred on how Thatcher rescued the British economy. Does the book reinforce this view of the Thatcher miracle?

No. As Jim Tomlinson argues, the record of the Thatcher governments on inflation, growth and productivity was patchy. There were inflationary spikes towards the beginning and end of the decade, unemployment reached heights not seen since the 1930s and an escalating exchange rate did lasting damage to Britain’s industrial base. But the larger argument of the book was that we need to change the way we approach such questions. ‘The economy’ is an abstraction: an aggregate of statistics. The economic experience of Thatcherism varied dramatically from one part of the economy to another. For financial services, IT and the oil industry, there was indeed an economic miracle; for mining, heavy industry and the low paid, there was not. Thatcherism produced winners and losers – which is why memories of the period are so polarised.

On Tuesday Radio 4’s Today programme following dedications to Thatcher finished rather abruptly on a note of agreement that she was very lucky in government. Is there evidence for this position in the book?

There were certainly moments when the dice rolled favourably. If Ted Heath had resigned in 1974; if Callaghan had gone to the polls in 1978; if the Falklands War had been delayed, her path to the top would have been considerably bumpier. For most of her premiership, she benefited from a divided Opposition and an electoral system that delivered landslide majorities on a very limited share of the vote. She enjoyed booming revenues from North Sea oil, without which her tax cuts and the defeat of the miners would have been much more difficult to achieve.

But no politician is in total command of their destiny, and Thatcher’s luck was always mixed. She inherited a shrinking party that had lost four of the last five elections. She led an often mutinous cabinet at a time of economic crisis, against a level of personal vitriol to which no other modern leader has been subjected. She was almost assassinated by the IRA and lost a number of friends and allies to paramilitary violence. Like all politicians, Thatcher had to play the hand she was dealt – and she played it more successfully than her opponents.

What effect do you think that the death of Margaret Thatcher will have on the Conservative Party in the coming months and years?

The Conservatives are going to try very hard to entrench a positive memory of Mrs Thatcher, and to wrap themselves in her mantle. They’ll present her as someone who took the tough decisions necessary to rescue a broken economy – and they’ll represent Labour as a party on the wrong side of history then and now. We may also see a tougher rhetoric on Europe, to shut down the attempt by UKIP to claim Thatcher for themselves. Yet Thatcherism remains electorally toxic in large parts of the United Kingdom, so this is likely to reinforce the return to a heartland vote strategy.

No Comment