As expected, the recent NATO Summit was dominated by President Trump’s blunt criticisms of allies. He accused European member states of taking advantage of the United States, of failing to follow through on the 2014 agreement to raise defence spending to a minimum of 2% of GDP, and cozied up to Russia, perhaps most shockingly given the accusations levelled at his own campaign, of colluding with Russia. The basis for these accusations should be taken seriously, even if the latent threat of the United States withdrawing from NATO and the capricious means of delivery seem designed more to appeal to American domestic political interests than to truly illicit reform of the organisation. Cutting through the hyperbole, we see that there are legitimate questions about NATO’s purpose and role in the contemporary world.

The conventional Russian threat, then and now

The purpose of NATO was to provide a security guarantee from the United States to Western European states which by themselves lacked the economic and military resources to oppose the Soviet Union in either a conventional or nuclear war. Over time the organisation focused on security coordination, that is, NATO moved beyond a unilateral security guarantee to also being a means of quickly mobilising multilateral resources, to integrate and harmonise military resources to reduce duplication and inefficiencies, and emphasised mutual defence. Absent the existential threat of the Soviet Union, it was widely supposed that NATO would wither and die, and yet it endured, expanded, and continues to be the lynchpin of the European security architecture.

NATO’s raison d’être has been re-invigorated since 2008. It has been key in coordinating the militaries of member states against Russian revanchism, and to provide a centralised body through which deterrent threats can be clearly and forcefully issued. The wars in Georgia, Ukraine and Syria, and widespread accusations that Russia has sought to influence elections in Europe and North America, as well as increased military spending suggest the re-emergence of Russia as a threat. However, this threat is far lower than it ever was during the Cold War. Although the underlying nuclear threat remains, Russia poses little conventional threat to the United States or the major European members of NATO.

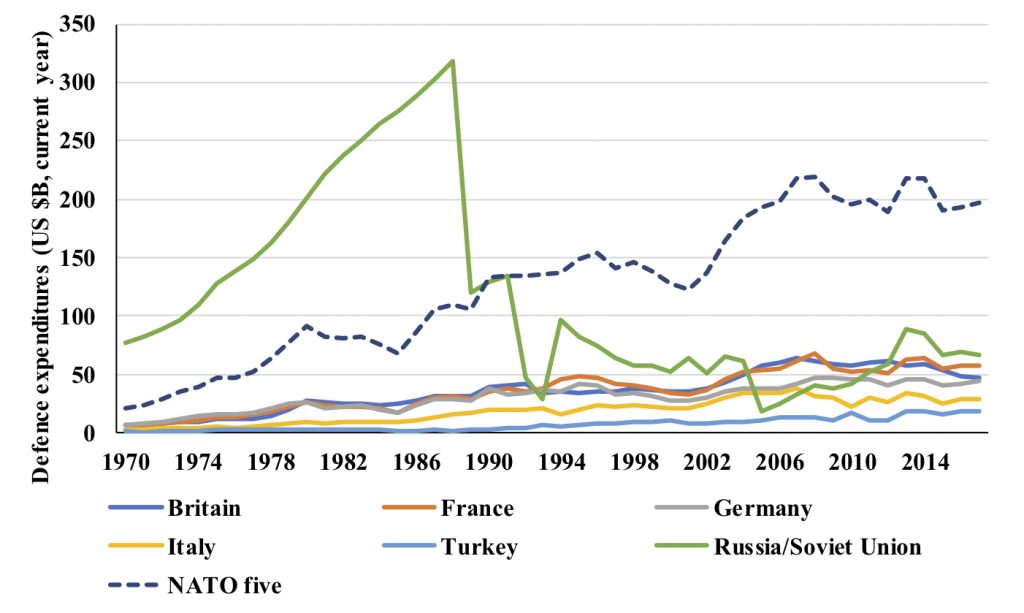

Chart 1 illustrates this by comparing military spending in in the Soviet Union/Russia, with those of the Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Turkey from 1970 through to 2017. As can be seen, military spending in Russia since 1990 has been comparable to that in these other five states, and though 2005-12 saw sustained growth, it has fallen back once somewhat since 2014. Moreover, the sum of the five NATO members grossly exceeds that of Russia today – and has done since 1990. Though the large Russian defence industry, and the close relationship it enjoys with the Kremlin, may stretch funds further than in any of these other states, Russia is today significantly less able to project conventional power than in the 1980s.

Chart 1: Comparative defence spending, 1970 – 2017

Note: Data 1970-2012 from Correlates of War, National Material Capabilities dataset. Data 2013-2017 from Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Military Expenditure Database.

The development of divergent Russian threats

The problem for NATO today is that different members experience quite different types and levels of threat from Russia. The Baltic States and Poland undoubtedly have real concerns about a conventional attack, but Western Europe does not. Instead, these states, and the United States, are faced with cyber threats, conventional espionage, and leveraging energy dependency. NATO was not conceived with such issues in mind and the latter two have continued to be dealt with either independently or through alternative organisational structures (e.g. Five Eyes). Especially in the areas of conventional espionage and energy security, member states have been keen to retain control, to allow them to pursue national interests.

Cyber security has recently become a priority for NATO. However, the extent to which this should be an area in which NATO is the primary means for coordinating and mobilising assets is debatable, though it can usefully serve as a venue for the exchange of best practices. NATO remains primarily a military organisation, but hacking has both military and civilian targets. Whilst it would be appropriate for NATO to bolster the resilience of militaries, particularly their command and control systems, communications, and equipment projects, the defining feature of Russian cyber-attacks have been the targeting of civilian institutions, firms and individuals. In such cases, the police and intelligence services are better suited to provide protection and counteract attacks. As the individual militaries that make up NATO have been set up to deal with largely conventional threats, it is not clear if and how the organisation as a whole can be tasked with providing cyber security.

Because of the divergent forms and levels of threat experienced by individual NATO member states, the organisation appears to be struggling to unite behind a common response. This is despite the clear advantages the organisation brings to its members in terms of coordination, training and sharing best-practices. The result of this lack of shared threat perception is the observable divergence over who should pay for what, since increasing military spending seems to bring little benefit for countries that do not experience a true conventional threat, but are preoccupied with emerging threats such as cyber security.

Conclusion

Russia remains the reason for NATO’s existence, but the threat for all is no longer of being overwhelmed by a massive conventional assault. Instead, Russia threatens some with conventional force, some with leveraging their energy dependency, others with espionage, and all with cyber threats. This unconventional, hybrid, or raiding strategy, cannot be countered through conventional means, which makes the solution of simply increasing military spending unsuitable. More money does not necessarily buy more security, unless it is well spent. While the Russian threat might work better to encourage increased defence spending than Trump’s bravado, the issue remains how any additional resources should be allocated. What are NATO’s priorities and role in an environment of divergent, evolving and increasingly asymmetrical threats? While the basing of trip-wire military forces in the Baltic States is likely enough to deter a Russian conventional attack, it is not entirely clear how NATO forces would, or should, respond to the appearance of ‘little green men’ or a cyber-attack against critical infrastructure.