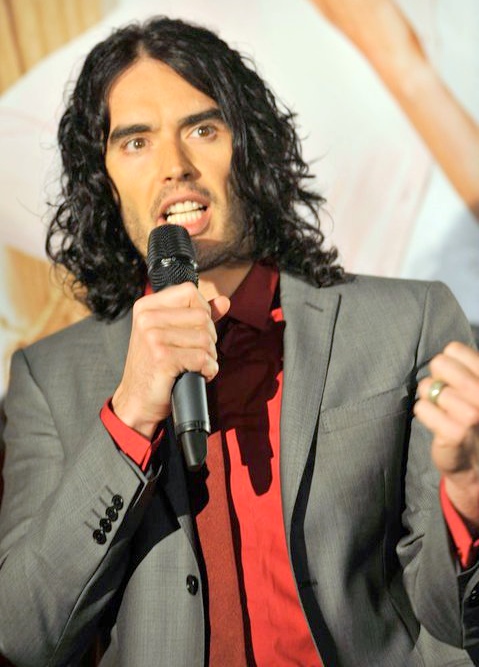

Russell Brand, the British comedian, used a guest editorship of the 100-plus-year-old leftist magazine New Statesman last month to call for a “total revolution of consciousness and our entire social, political and economic system.” Capitalism, and the ideology that sustains it — “100 percent corrupt” — must be overthrown. He also doesn’t think people should vote, as partaking in democracy would further the illusion that a rotten system could change. It was a call, albeit chaotically phrased, for a socialist revolution.

Born into the middle class, Brand’s childhood was disturbed: his photographer father left when he was six months old, his mother developed cancer when he was eight (but survived), he left home in his mid-teens and took to drugs. He later became a star, delighted in promiscuity, married the singer Katy Perry for a year and a half and grew modestly (by star standards) rich, with an estimated net worth of $15 million and a lovely new Hollywood millionaire bachelor’s pad.

None of this disqualifies him from speaking and writing seriously about politics, nor from calling for a socialist revolution. Marx was born into the upper-middle class, Lenin was a minor aristocrat by birth, Stalin studied to be a priest and Mao was the son of a wealthy farmer. Even Pol Pot came from a peasant family considered relatively wealthy by the standards of the times. All of these people called for, or launched, revolutions. No reason, then, to believe that a demand for a 21stcentury socialist revolution could not be launched from the Hollywood Hills, or from a BBC studio.

It’s interesting to speculate what such a revolution would look like. But Brand won’t play along: his article in the New Statesman and a subsequent Newsnight interview was long on florid rhetoric and denunciation, and wholly devoid of detail. Perhaps that’s best. Because let us not forget that the socialist revolutions of the 20th century were horrors, claiming more victims than Nazism — who were shot, starved, frozen and tortured to death.

Such revolutions, on past experience, are some of the world’s worst ideas. Its leaders launch them in the name of the suffering poor, using the reality of widespread misery to justify seizures of power — which brings much more misery. Brand followed that pattern: he went to Kenya on a Comic Relief trip and saw children foraging through a vast stinking trash dump for bottle tops, which have some value: later, at a Givenchy fashion show, he saw the skinny models and “could not wrench the phantom of these children from my mind.” The starving scavengers are the moral levers of his revolution.

Besides the crazy endorsement of the kind of revolution that has always descended into mass murder, his refusal to vote is a minor eccentricity. Yet the demand for a revolution, channelling the kind of violence, looting and murder seen in London and on other UK cities’ streets two years ago against “the source of (the rioters’) grievance” is much more delusional, much more seriously irresponsible towards the youth whom he admires for their refusal to take democracy seriously.

In his prolix, occasionally graceful rantings and writings, Brand touches on matters of great importance and danger. In developing societies, masses of people are dirt poor — literally, as Brand saw in the Kenyan dump, grubbing in muck for pennies, others breaking their back tilling dry soil, dying early. In wealthy societies, young men and women at the bottom of the social heap who drop out of school now cannot find jobs. Even those with a good education get stuck.

Men and women from lower-class backgrounds with talent — Brand is one of them — do get ahead, but there hasn’t been a general lifting of class barriers since the first two or three decades after the last world war. That happened in Europe and in the U.S. — where the generations born and living in the lower classes were formidably lucky. They ate much better, worked fewer hours in safer conditions, bathed more frequently (since they had bathrooms), had better healthcare and lived much longer than their predecessors.

They weren’t all grateful. A sizable cohort of the youthful boomers in the rich world was seduced by Marxism, and thought socialist revolution — “peaceful if we can, violent if we must” — was the next logical and necessary step. I was one, with fewer excuses than most: a severe childhood illness was cured by the (free) National Health Service, a university education paid for (in full) by the state. What was I thinking and doing? In any case, any socialist leaning was knocked out in my twenties, and sealed off by living and working in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union for a decade.

It may be knocked out of Brand. But it’s getting late: he’s 38, and still claims the mantle of a revolutionary socialist, who scorns all social democratic compromises and accommodations, since left-of-center politicians are, like all the rest, “frauds and liars.”

That last phrase reveals the real truth about Brand’s gasbagging. He deals in clichés, albeit dressed up in language that ranges from the baroque to the obscene. That politicians are self-serving liars is one of the largest tropes of both journalism and show business, a tired pseudo-radicalism balanced between ignorance and envy. Talented comedian though Brand is, offstage he tries on postures like a rich woman does dresses. This one, the revolutionary, might not last a flight back to Los Angeles.

Modern developed societies won’t have revolutions unless they break down in chaos, which is always a possibility. They have developed a complex structure of classes, incomes and property holdings. In most countries, the majority of people have a property stake they don’t want to lose, however modest it is. But at present, in the rich countries, we see wild excesses of wealth with deep (if relative) poverty, together with large (if diminishing) real poverty in the developing world.

The best that can be done is to warn of the adverse consequences of deepening poverty underlying wild riches, and to support those policies and forces that can reform a socially perilous and probably unsustainable situation. That takes time, and work, by activists, scholars, social groups, parties and the “frauds and liars” in council chambers and parliaments. Maybe Brand will mature, and join in before he’s 40.

This post originally appeared on John Lloyd’s Reuters blog.

1 Comment

Well-written on the person of Brand. He brings no useful analysis to politics, and we can convincingly argue he is attention-seeking, vain, crude and hypocritical.

But Brand is popular. The editors of the New Statesman clearly felt their gimmick would help sell papers. Let’s ask WHY he is popular. Do a few lefties just feel nostalgic for the revolutionary proclamations of yore? Does Brand express widely held scepticism of modern markets and politicians’ ability to deal with the challenges of poverty and the wealth gap?

Brand pollutes the minds of millions every day through the entertainment industry. It is sickening that his place in that industry can be used to exert political influence. But only when we know why he has been able to influence public debate might we learn how to use such methods to enrich political debate constructively.