Many people know that it is electors in the electoral college that actually elect the president, not citizens voting on election day. They also may know that this system allows the candidate coming in second to win the election, as occurred in 2000, and thus violates the democratic norm of equality in voting. But more puzzling (and less reliable) are the arguments made on behalf of the electoral college. Here are four of the most common — and why they are wrong.

1. The electoral college protects the interests of small states

The core justification is that it balances local and national interests, protecting small states from majority rule. Yet states with small populations do not have common interests to protect and individual states in general do not embody coherent, unified interests either. Nor is there a need for protection. Given the many constraints the US Constitution places on the acts that simple majorities can take — like the extraordinary representation of small states in the Senate, and the power of the filibuster to thwart majorities — it strains credulity to argue that certain geographically concentrated interests require added protection from the majority of Americans.

Do we really desire a presidency responsive to parochial interests in a system that is already prone to gridlock and which offers minority interests extraordinary access to policymakers and ample opportunities to thwart policies they oppose?

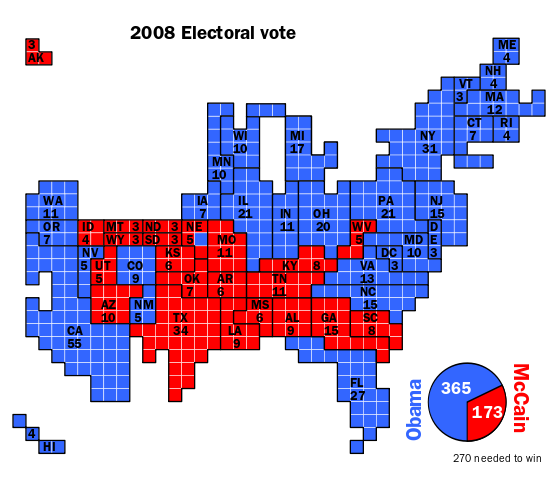

Equally important, presidential candidates do not focus on local interests in their campaigns. Indeed, they do not even show up in most states. The electoral college distorts the political process by providing an incentive to visit competitive states, especially large competitive states. In the 2008 general election, Barack Obama and John McCain personally campaigned in only 5 of the 29 smallest states, and they also bypassed many of the largest states. Moreover, they did not compensate for their lack of visits through advertising.

2. The electoral college forces candidates to obtain concurrent majorities around the nation

According to its supporters, one of the primary virtues of the electoral college is that winning candidates must obtainconcurrent majorities from around the country to win, rather than appeal to clusters of voters whose votes could be aggregated across states and regions but nevertheless might not represent all strata of society.

Be we have seen that candidates of both parties virtually ignore large sections of the country in their campaigns, and we know that candidates rely heavily on regional support.

Moreover, the electoral college does not produce presidents who have won major social strata in the country. In 2000, George W. Bush did not win the following groups: women, Blacks, Hispanics, Asian-Americans, Catholics, Jews, those with a high school education or less, those with postgraduate education, liberals, moderates, urbanites, those with less than $50,000 of household income, voters 18-29 and 60 and older, or those living in the East and West. This vote certainly did not represent winning concurrent majorities across the major strata of American society.

3. The electoral college prevents fragmentation of the party system

Some argue that direct election of the president would fragment the party system because there would be a runoff if no candidate received, say, 40 percent of the vote. The runoff would provide an incentive for third parties, which would hope to attract enough votes to prevent either of the two major party candidates from winning in the first round and thus position themselves to extract concessions in return for their support in the runoff.

There is no need for a runoff, however. No president has ever won with less than 40 percent of the vote (Lincoln received the lowest percentage at 39.8, but was not on the ballot in ten states). Americans regularly elect presidents without a majority vote under the electoral college: Truman (1948), Kennedy (1960), Nixon (1968), Clinton (1992, 1996), and George W. Bush (2000).

In truth, without a runoff, direct election discourages third party candidates because a party must win the entire country to win the presidency. Coming in second or third gains a party no leverage in the selection of the president.

By contrast, the unit rule (by which states award all their electoral votes to the plurality winner in the state) that 48 states employ under the electoral college encourages third parties, especially regional candidates like Strom Thurmond in 1948 or George Wallace in 1968. Winning a few states may deny either major-party candidate a majority of the electoral vote and put a third party in a position to dictate the outcome of the election. Imagine Thurmond or Wallace extracting concessions for their support. Under direct election there would be no possibility of deadlocking an election because there would be no electoral votes to win.

In addition, under the electoral college a third party can tip the balance in a closely contested state by siphoning a few votes from a major-party candidate. In 2000, Ralph Nader cost Al Gore both Florida and New Hampshire and thus the election. Under direct election, third parties could not distort the voters’ preferences in a state.

4. Under direct election, candidates would campaign only in large cities

One often hears that under direct election, candidates would ignore most of the country, campaigning only in large cities. Yet we know that the electoral college provided incentives for candidates to ignore most of the country, especially rural areas. Small states could not be worse off than they are now.

However, in a direct election, every vote would count equally and candidates would have an incentive to appeal to all voters, not just those strategically located in swing states. Moreover, because the cost of advertising is mainly a function of market size, it does not cost more to reach 10,000 voters in Wyoming than it does to reach 10,000 voters in a neighborhood in Queens or Los Angeles. Actually, it costs less, and there are more swing voters in the smaller markets than in urban areas.

Under the electoral college it makes no sense for candidates to allocate scarce resources to states they either cannot win or are certain to win, in which case, the size of their victory is irrelevant. However, making every vote in every state count toward electing the president under direct election would stimulate state party-building efforts in the weaker party, especially in less competitive states, and encourage both parties to campaign actively. Increased mobilization would inform voters and increase turnout. Moreover, people are more likely to vote if they think their vote matters.

George C. Edwards III is the Winant Professor of American Government at Oxford and University Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Texas A&M University.

This post is part of Elections 2012, a collaborative project between the Rothermere American Institute and the Departments of Politics at Oxford and Cambridge Universities.

2 Comments

Presidential elections don’t have to be this way.

The National Popular Vote bill would guarantee the Presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states (and DC).

Every vote, everywhere, would be politically relevant and equal in presidential elections. No more distorting and divisive red and blue state maps. There would no longer be a handful of ‘battleground’ states where voters and policies are more important than those of the voters in more than 3/4ths of the states that now are just ‘spectators’ and ignored after the conventions.

When the bill is enacted by states possessing a majority of the electoral votes– enough electoral votes to elect a President (270 of 538), all the electoral votes from the enacting states would be awarded to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states and DC.

The presidential election system that we have today was not designed, anticipated, or favored by the Founding Fathers but, instead, is the product of decades of evolutionary change precipitated by the emergence of political parties and enactment by 48 states of winner-take-all laws, not mentioned, much less endorsed, in the Constitution.

The bill uses the exclusive power given to each state by the Founding Fathers in the Constitution to change how they award their electoral votes for President. Historically, virtually all of the major changes in the method of electing the President, including ending the requirement that only men who owned substantial property could vote and 48 current state-by-state winner-take-all laws, have come about by state legislative action.

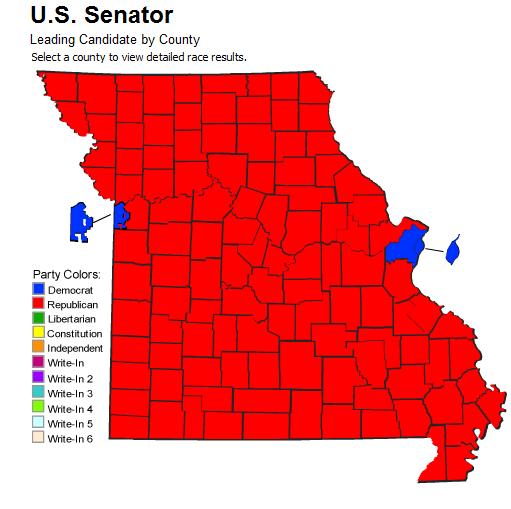

In Gallup polls since 1944, only about 20% of the public has supported the current system of awarding all of a state’s electoral votes to the presidential candidate who receives the most votes in each separate state (with about 70% opposed and about 10% undecided). Support for a national popular vote is strong among Republicans, Democrats, and Independent voters, as well as every demographic group in virtually every state surveyed in recent polls in closely divided Battleground states: CO – 68%, FL – 78%, IA 75%, MI – 73%, MO – 70%, NH – 69%, NV – 72%, NM– 76%, NC – 74%, OH – 70%, PA – 78%, VA – 74%, and WI – 71%; in Small states (3 to 5 electoral votes): AK – 70%, DC – 76%, DE – 75%, ID – 77%, ME – 77%, MT – 72%, NE 74%, NH – 69%, NV – 72%, NM – 76%, OK – 81%, RI – 74%, SD – 71%, UT – 70%, VT – 75%, WV – 81%, and WY – 69%; in Southern and Border states: AR – 80%,, KY- 80%, MS – 77%, MO – 70%, NC – 74%, OK – 81%, SC – 71%, TN – 83%, VA – 74%, and WV – 81%; and in other states polled: AZ – 67%, CA – 70%, CT – 74%, MA – 73%, MN – 75%, NY – 79%, OR – 76%, and WA – 77%. Americans believe that the candidate who receives the most votes should win.

The bill has passed 31 state legislative chambers in 21 states. The bill has been enacted by 9 jurisdictions possessing 132 electoral votes -49% of the 270 necessary to go into effect.

NationalPopularVote

Follow National Popular Vote on Facebook via NationalPopularVoteInc