From the coverage of the US election in the UK news media it would be easy to get the impression that we are witnessing a single battle of giants, or a least of the giantly funded. In mid-October the Center for Responsive Politics reported that the campaigns of Mitt Romney and Barack Obama had raised almost $900 million combined. The Center also reported that various committees had spent over $376 million to support or oppose the presidential candidates. Given an inevitable reporting delay, and with only a few shopping days left before Election Day, there remained plenty of opportunity for these figures to grow. At the same time the candidates were pretty much tied in the opinion polls. The presidential debates attracted consistently high audiences (and they did matter after all!). Obama vs. Romney seemed to be the only show in town. But of course, that is not so. Money is flowing in all directions.

From the coverage of the US election in the UK news media it would be easy to get the impression that we are witnessing a single battle of giants, or a least of the giantly funded. In mid-October the Center for Responsive Politics reported that the campaigns of Mitt Romney and Barack Obama had raised almost $900 million combined. The Center also reported that various committees had spent over $376 million to support or oppose the presidential candidates. Given an inevitable reporting delay, and with only a few shopping days left before Election Day, there remained plenty of opportunity for these figures to grow. At the same time the candidates were pretty much tied in the opinion polls. The presidential debates attracted consistently high audiences (and they did matter after all!). Obama vs. Romney seemed to be the only show in town. But of course, that is not so. Money is flowing in all directions.

At US Senate level a further $554 million had been raised by all candidates (including those who lost in the primaries) for this year’s 33 US Senate seats up for grabs, and $977 million more in pursuit of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives. Certainly it would not feel like the presidency is the only game in Massachusetts, where a tightly fought Senate race attracted war chests amounting to $58 million between the competing candidates, Scott Brown, the Republican incumbent, and Elizabeth Warren, his challenger. Nor will the executive be the only competition voters were thinking about in Minnesota, Ohio and Florida where individual races for House districts each attracted around $20 million to the campaigns. Elections for state and local offices, referenda and other items on the ballot add hundreds of millions more to campaign costs, and enrich the variety and texture of American democracy.

There was talk in 2008 of the ‘billion dollar election’, and certainly the decision of Obama to forego federal election matching funds for the general election signalled a sea change in presidential campaign expenditure. Nevertheless, the declaration of the billion dollar election ignored the fact that the quadrennial general election in America has been a billion dollar event for decades — election campaigns at the federal level alone have achieved an aggregate spent in excess of a billion dollars since the 1990s. This is long before the Supreme Court ruled on Citizens United, a case often blamed for the greenback deluge.

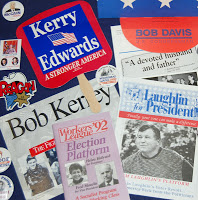

It is not surprising, in a country with approximately half a million elected offices, where about 133 million people voted in 2008, and with ballots that can call on voters to make dozens of decisions, that the aggregate costs of campaigns and elections mounts. And while the largest expenditure category in many campaigns is on TV advertising, there are also posters, billboards, lawn signs, leaflets, buttons and all kinds of other material that still flowers bountifully in the USA, especially in the late stages of close elections. These materials try to engage voters with the elections in their communities, on the road, in the street. They are used by campaigns to leave a personal touch when canvassing, to energise canvassers at rallies, to keep their candidates’ names in front of potential voters wherever they may be. Many of those half million public offices – especially at local level – never get as far as the TV, and still rely almost wholly on these traditional materials.

The archive at the Vere Harmsworth Library at the Rothermere American Institute gives a small idea of the range of offices that exist in the USA, the reach and depth of electoral democracy in this nation and the variety and energy of the campaigns. The collection is necessarily always a little behind the times, but the races of 2012 will shortly join the materials (as some already have), dating back to the mid 19th century, already housed at the library.

Philip Davies is the Director of the Eccles Centre for American Studies at the British Library.

This blog is part of Elections 2012, a collaborative venture between Politics in Spires and the Rothermere American Institute.

No Comment