Those that define internet standards shape our thinking and hold the key to our freedom of communication—no trivial task. Yet tech policy is seen as boring, a yawn-inducing issue offloaded to engineers, corporate lawyers, research universities, and government ministries. In the previous age of global internet governance, regulations and protocols were outsourced to technocrats (and a few “civil society” NGOs agitating on the margins). However, in this age of “techno sovereignty,” where everything from 5G to TikTok is capable of causing geopolitical conflict, there is no more consensus. In short, we demand protocols, not platforms. But who’s going to get us there? Meet the stacktivists.

What is the Stack?

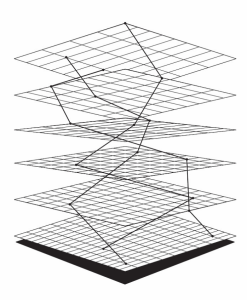

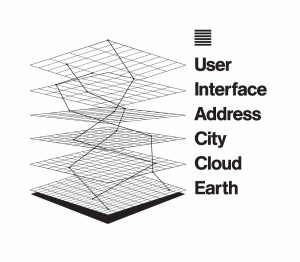

Benjamin Bratton’s The Stack (2016) can be useful to bounce ideas against when we want to define the state of the art in technology, urbanism, design, and activism. The book stacks layers, one on top of the other, starting with Earth as the foundation. The first layer is occupied by Cloud, then City, Address, and Interface, with the User on top. As Marc Tuters notes in a review of the book, “The Stack model is intended to include all technological systems as part of a singular planetary-scale computer, a kind of Spaceship Earth 2.0, updated to reflect the demands of the Anthropocene era.”

Grand designs such as The Stack can be read as a proposition to connect the dots while also containing encrypted insights for the few “careful readers.” But what if the planetary dreaming is nothing but a “retropia,” a backwards-looking utopia that nostalgically wants to return to the self-evident command enjoyed in the Clinton, Bush, and Obama years? In the regressive, confused, and turbulent times of Trump and Biden, no one seems to be sure about U.S. world domination and its “protocolistic” hegemony. Stacktivism starts and ends with the desire to reclaim the internet.

To get there, we need to speak truth to power, to kick against platform realism. Bratton argues that we “have to build a politics capable of engagement with the full complexity of reality” (2021, p.9). OK, but how much of this is ordinary dealmaking in some hotel conference room with Big Tech engineers and lobbyists, and how much is driven by open and inclusive forms of self-organisation? Dealing with the technical and legal language of protocols and standards is a profoundly dirty and long-term business that is crying out for a new generation to take up the task. In this age of geopolitics, is it a lie or an act of liberation to call for a deliberate plan for the coordination of the planet, as Bratton does? Who’s speaking, in an era where political representation through nation states was supposedly ditched decades ago? Is there any legitimacy to speak on behalf of billions of users? What claim can a critical, oppositional, commons-driven movement make in such an instance?

The Limits of Stacktivist Thinking

What type of speculative thinking do we need in this disaster era of climate change, growing inequality, and real existing geopolitics? In a turbulent world, where the administration of the present is delegated to the dazed and confused, ideology design is up for grabs. Let’s refine the art of strategic forecasting in these times of collapse while not being naive about the collective power of “making worlds.”

Lately, “the stack”—once only a technical term used by engineers and geeks – has jumped context and transformed into a general container concept, placing it in danger of becoming an empty signifier. As a meta-concept, the stack has been detached from its author and his Californian-nihilist program for the aspirational cool crowd and turned into a tool for bringing together interrelated crises: climate change, inequality, AI and automation, and COVID-19. To determine, to think technologically, remains of utmost urgency. Therefore, contra Bratton, it is precisely the “stacking” of issues, factors, and contexts that will bring us further into the constitutive force of technical systems.

As an abstract model describing the architecture of the internet, the Stack provides us with a useful spatial division of layers such as protocols, data, applications, and user interfaces. Bratton’s notion of The Stack comes out of the U.S. postmodern literary tradition of cognitive mapping (Jameson), which seeks to make intelligible (and containable) complex processes. Bratton combines this approach with other forms of mapping. We might think, for instance, of the decade-long attempts to visualise the vertical integration of technologies, or classic network maps that aim to capture relations between different players. In a sense, he strives to transform 2D tech engineering plans into 3D models that provide a portrait of planetary transformation. His aim is to produce a general network theory able to provide deeper insights into the dynamics of power.

Bratton also invites us to think through technology in relation to geopolitics and location. In this sense, The Stack can function as a kind of method or approach. However, the book is purposefully vague about how material infrastructure and ideology relate. In the light of Trump, Putin, and Xi Jinping, Bratton’s global engineer seems a tragic, retrograde figure.

Reimagining the Stacktivist

Let’s define stacktivism as an active and reflective reading of stacks-on-the-move. This definition is not afraid of the subject (formerly known as the user). And this definition involves action committed by confused, selfish, or messy players. This messiness provides space for grassroots interventions that refuse to accept the current configuration of “the stack” as a given. In comparison with hacktivism and (tactical) media activism, stacktivism can be considered counter regressive as it takes into account the real-existing totality of today’s interrelated tech-architectures, as opposed to the shrinking paranoid world of the online self that is in constant danger of collapse under the weight of its own self-image, surveillance, precarity, and depression.

Following Caroline Levine (2017), we can state that the stack must be whole and complete, holding in unity the different parts, from protocols, interfaces, routers, cables, and antennas, to content and metatags. The digital has brought on a seamless and subconscious unity of technics and life. A critical emphasis on the invisible technical wholeness helps us to fight naive and romantic gestures of resistance and face contemporary forms of abstract violence. As Saskia Sassen explains, expulsions from life projects and livelihoods, from membership, and from the social contract at the centre of liberal democracy, are now a reality (2014, p.29).

However, the stack as a unity of contradictory, heterogeneous elements is never entirely closed. Systems turn out to be unstable, temporary, and open, not out of idealism but simply as a result of their flawed, all-too-human design. This is a basic notion that can be adapted from hacking and cyber warfare. Put simply, We Are Infrastructure. In line with Bratton, stacktivism claims to oversee all levels. It grasps the politics of code, algorithms, and AI. It is aware of the behavioural science manipulation of moods through careful interface design choices. This hyperawareness comes at a high price: not everyone is a stacktivist.

Stacktivism is a sovereign attitude. It is distinctly human but not frantically searching for a “correct” form of representation. In that sense it could be considered post-democratic and post-identity. Unlike the tactical media interventions of the 1990s, stacktivism is—by definition—abstract and conceptual in nature, recognising that code is power and power is code. How to dismantle invisible power? Do we fight abstractions with abstractions, design with counter-designs? I love Phil Agre’s observation that architecture is politics, but should not be understood as a substitute for politics. Decentralised protocols are too readily assumed, because of their technical qualities, to bring about decentralised political, social and economic outcomes. A more fine-tuned appreciation of the social dimensions of the stack is likely to improve things in this regard.

What matters now is who owns the internet in terms of data centres, cables, and PR—and that question must be investigated, first and foremost, through a material analysis.

Stacktivism Today

The “stacktivist dilemma” is a classic one: how can the multitudes gain power while pulverising power at the same time? The digital is now an encompassing global sphere. We’ve left the era of technology-as-tool far behind us. The nasty feedback machines strike back and try to corner us, suppressing our desires and needs, even without us noticing the closing down of communication and expression. Can the stack (formerly known as the internet) only be understood in its totality once it has fallen from its unity and been reduced to fragments (read: geopolitical blocks and national webs)? Can we be global in scope on the protocol level, yet act locally in networks of strong-ties? Is it productive to consider cosmotechnics for good—stealing code from the rich and inserting it into networks for the poor, in the spirit of Aaron Schwartz and Anonymous’ SkyNet? Do you also believe that another WikiLeaks is possible, this time without the celebrity cult?

The challenge now is to unleash political tech movements, design campaigns, and establish many think tanks. The task is to raise new code-loving generations for whom autonomy and techno self-determination are as natural as the seamless 24/7 smartphone connectivity is for us. Refusal and exodus are one, together with alternative tools. Forgetting and deprogramming are one part of this exit plan. As Jenny Odell proposed, doing nothing in the attention economy is an act of political resistance, a strategy “for any person who perceives life to be more than an instrument and therefore something that cannot be optimised” (2019, p.xi).

What we will do next is to act together. The starting point in designing the new techno-social must be the group rather than the individual user—the social not the individual. Tools will be temporal and goal-driven, focused on what needs to be done now, not sharing for the sake of it. In this way we move from profile to project, from merely liking to collective decision making, from behavioural to social psychology, from influencers to cooperation, from trolling to debates. In this sense, stacktivism is only one of many options. Distributed forms of collective design will remake life from the swamps.

This post is an edited extract from the work Sad By Design: On Platform Nihilism first published in 2019. With thanks to Jamie Ranger.

Bibliography: