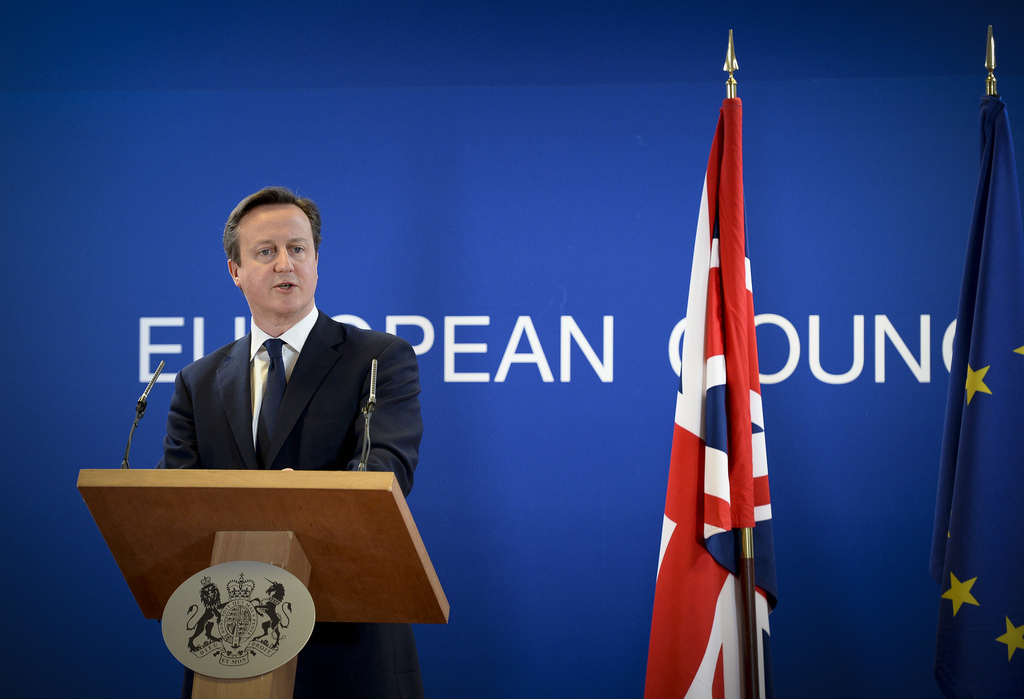

With the Conservative party’s unexpected victory in the May general election, Prime Minister David Cameron has now managed to deliver on a promise made in his European Union (EU) speech of January 2013: an in-out referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU. In this article, Kai Oppermann and Paul Taggart argue that Cameron’s pledge originated in three interrelated developments: the policy of previous Labour governments; rifts within the Conservative party over Europe; and the rise of UKIP.

The UK referendum on EU membership may be many months away but with David Cameron laying out his stall with other European leaders, we should be clear that we are embarked on the journey and already some way down the track. It is easy to think of referendums as one-shot deals but in reality they are not. Rather, referendums are long-term games and in this case the game was started in 2013. And it’s easy to think of this as a European process, but whatever grand meals may be consumed in other European capitals, this is very much a result of domestic British politics. The EU referendum is largely down to domestic drivers and the result will likely be shaped as much by the party politics between and within UK parties as by European factors.

It is useful to think about EU referendums in terms of a four-stage process that starts with the pledging of referendums. The UK has been at this point before and the commitment to an in-or-out referendum is not the first pledge we have had on European referendums, which were often as much about containing an issue or attempting to stem opposition in the domestic arena as they were about European decision-making. Second, we have the stage of the European negotiations. And although these look like grand international events, they are bargains struck with all participants, particularly Cameron playing with one eye squarely on domestic politics. Then there is the campaign and finally the result and its implications.

So how did we get here?

The key driver behind the upcoming referendum on the UK’s EU membership is domestic politics. When David Cameron made the commitment in January 2013 first to negotiate a ‘new settlement’ for Britain in the EU and then to put this settlement to a public vote by 2017, the main rationale was the short-term domestic expediency of such a move. This is the latest in a long line of domestically driven EU referendum pledges in British European policy. From Harold Wilson in 1975 opting for a referendum to quell internal disquiet in the Labour Party, to Tony Blair’s pledge on the single currency and the constitutional treaty as gambits to close down the European issue for an election but to encourage conflict within the Conservatives, EU referendum commitments have been driven largely by British politics. This is also the case for David Cameron’s pledge to hold a referendum, which originated in three interrelated developments.

First, the policy of the previous Labour governments under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown has had a significant impact on how Europe is perceived in the British debate. Despite Blair’s early commitment to champion Europe, New Labour after a brief honeymoon with the EU remained consistently mute in supporting European integration as it saw the advantage of letting the Conservative Party in-fight on the issue. This had the effect of defusing the European issue in the domestic arena and of closing down debate about Britain’s place in the EU and creating the space for Eurosceptic sentiments and referendum demands to flourish in British political discourse. Labour governments have largely failed to actively seek a broader domestic consensus for their relatively pro-European approach and to challenge the deeply engrained scepticism towards European integration in British politics. If anything, this has only reinforced the perception of a disconnect between mainstream elites and public concerns which Eurosceptic political entrepreneurs have been able to mobilise.

Second, the referendum commitment was a means of managing intra-party divisions on Europe within the Conservative party. Since he became party leader, Cameron has done little to resolve these divisions but has mainly relied on keeping the issue low on the intra-party agenda and on placating hard Eurosceptics within his party with largely symbolic gestures such as pulling the Conservatives out of the European People’s Party grouping in the European Parliament. Holding his backbenchers in check on Europe has been ever more difficult to achieve, however, given the disproportionate number of hard-line Eurosceptics among the 2010 intake of Conservative MPs and the increasing discontent on the Conservative backbenches with the constraints of being in a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. In this context, the demand for an in-or-out referendum became the main stick of Eurosceptic Conservative backbenchers with which to beat the party leadership. The decision of David Cameron to give in to such demands was thus another attempt to defuse the mobilisation of hard Euroscepticism within the Conservative party and to paper over intra-party divisions on Europe at least until after the 2015 general elections.

Third, Cameron’s referendum commitment cannot be understood without the rise of UKIP. On the one hand, UKIP’s appeal was itself facilitated by the complicity of Conservative and Labour leaders in downplaying the issue in the domestic political debate. At the same time, UKIP has further mobilised Eurosceptic sentiments in British public opinion and works to increase the overall salience of European policy in British party politics, making it ever harder for the mainstream parties to evade political debate on the issue. This prospect must have looked particularly threatening to the Conservative leadership both because it fuelled intra-party divisions on Europe and because UKIP was expected to draw its support primarily from voters who would otherwise vote Conservative. In response, David Cameron thus relied on the tried and tested method to use EU referendum commitments in order to decouple European issues from domestic electoral agendas and to defuse the appeal of Eurosceptic challengers.

There would not be a referendum on Britain’s membership to the EU anytime soon if it had not been for the domestic political pressures on the leadership of the Conservative party for such a vote. Indeed, the referendum commitment has worked quite well for the Conservatives in the domestic arena, at least in the short term. In particular, it has helped the Conservatives to contain the salience of European policy in the 2015 general elections and to reduce the appeal of UKIP in key marginal seats. Moreover, Cameron’s decision to pledge the referendum was confirmed by the election result. The election returned a Conservative majority government which is committed to the referendum and which has already introduced legislation to make it happen. And the Labour Party, which had opposed the referendum during the election campaign, has now come out in support of the vote. The Liberal Democrats, demoralised as they are by the election result, support the referendum as well. This is also the case for UKIP, which will relish the opportunity to present their Eurosceptic case directly to the electorate, in particular since they were not able to translate their electoral support into a strong representation in Westminster. In other words, David Cameron’s commitment to an in-or-out referendum on Britain’s EU membership primarily for party political reasons has fundamentally reshaped the terms of the British domestic debate on Europe but it also has huge implications for both the UK and European integration in general.

No Comment