When American voters go to the polls on November 8, they will bring to an end an election cycle that has wholly captivated and sometimes shocked the nation. On that day, the United States will elect its 45th President, and the electoral college map will once again assume the shades of red and blue.

As of high summer, Hillary holds a commanding lead. But in an election cycle marked by unpredictable twists and turns, the tide may yet turn several times before polling day.

This special blog series, USA Decides 2016, focuses on the intersection between election coverage and political science, bringing together insight from our academics and students on an election posing a range of contested questions. How is electoral data changing? Will more blue-collar voters drift to the GOP column? What does this election say about the power of political parties? Can the centre-left hold on to power in a year defined by populism?

Join the Oxford University Politics Blogs to engage with our regular coverage. If you are an academic or student interested in contributing, please contact our editorial team through the contact link above.

The Final Hundred Days: Conventions, Questions, and Conclusions

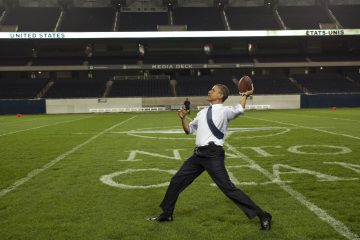

Primaries as Sports and Spectacle: Sports Metaphors in Twenty-First Century Presidential Primary Debates

Clinton v. Trump: How Hillary Wins the Narrative Game