Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, the husband and wife authors of the new book Zoopolis: the political theory of animal rights, believe that not only should animals have basic rights but that they (or at least some of them) should be accepted as full citizens in our political communities. In doing so they move the ‘animal rights’ debate from ethics to politics.

Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka, the husband and wife authors of the new book Zoopolis: the political theory of animal rights, believe that not only should animals have basic rights but that they (or at least some of them) should be accepted as full citizens in our political communities. In doing so they move the ‘animal rights’ debate from ethics to politics.

This is an intriguing topic with little application. It is a radical thesis which will appeal to almost no one. Indeed, some of its implications border on the ridiculous. Yet it is surprisingly hard to refute and will take the debate about the limits of liberal citizenship into radical new areas.

The authors start from recent developments in citizenship theory – an area in which Kymlicka’s ideas on the rights of minority cultural groups have had a major influence. He begins by talking about disibilities. Full citizenship, in the strong sense of active democratic political agency, is the central organising principle of the contemporary disability movement. Political agency for some disabled people cannot be conceived in the usual terms of (Habermasian) deliberation or the (Rawlsian) giving of publicly-intelligible reasons. People with serious mental disabilities, for example, may not be able to communicate linguistically or judge how political platforms might impinge upon their interests. This has led a number of theorists to argue for types of ‘supported decision-making’ and ‘assisted agency’ in which collaborators help elicit and interpret disabled people’s preferences and conceptions of the good. Because we all spend substantial periods in situations of dependency, standard models of citizenship overlook the way such assisted agency is a normal part of every human life.

This helps us, apparently, understand animal ‘dependants’. Although it isn’t framed quite so bluntly, Kymlicka and Donaldson offer a choice of biting one of two bullets. In terms of incoherence, either we deny full citizenship to certain humans (disabled, young, etc.) or we grant citizenship to those animals with which we can communicate. The ineluctability of this choice is hammered home by a series of arguments designed to prove that we stand in a duty of justice to ‘sentient selves’ rather than ‘moral persons’ in some rationalistic sense. Sentience is defined as ‘a capacity shared by all beings for whom the struggle for life and flourishing matters, whether or not the the being in question has a reflective sense of which things matter or how they matter’. Rather than tackle in detail the thorny problem of drawing a firm lines between selves and objects, the authors propose that a subject exists when there is the possibility of intersubjective recognition between us and that subject.

Animal rights theorists, meanwhile, have thus far been concerned with ethical questions about the duties owed to animals due to their intrinsic moral worth. But – just as our human rights underdetermine our rights as citizens of a particular country – the ‘human rights’ of animals (grounded in intrinsic moral status) under-determine rights (and duties) owed to (and by) individual animals on the basis of their relations with other human and animal community members. Zoopolis breaks new ground by looking at animal rights from a genuinely political perspective.

To that end, the majority of the book is spent examining the multiple ways animals and humans form communities and draws out implications for the kind of rights and duties owed in each kind of community. Domestic animals, it is argued, should be regarded as full citizens with legal rights and complex sets of positive duties owed to them. Wild animals are not owed citizenship rights but should be regarded as members of sovereign communities and granted the animal equivalent of universal human rights. So called ‘liminal animals’ with whom we have limited but important interactions – urban foxes and birds, dormice reliant on hedgerows for their ecological niche, stray cats and the like – occupy a complex middle ground.

The book is replete with examples of animal agency and and interspecies communication. We hear the story of Lulu the house-pig who sensed something was seriously wrong with her owner Joanne and ran of the house to get help, drawing blood as she squeezed through a dog door. When a driver found her lying in the road he was led back to the kitchen, where Joanne had just suffered a heart attack in the kitchen. This and less melodramatic examples of interspecies interaction are intended to illuminate the fact of our common community with animals and our duty to respect their rights and needs in exactly the way we would those of semi-dependent human community members.

When it gets into the nitty-gritty of radical animal rights and duties it also inevitably comes across as pie in the sky to those who are not fully convinced by the strong animal rights thesis. A favourite moment was the optimistic claim that there ‘is growing evidence that dogs can thrive on a (suitably planned) vegan diet’ and the ensuing discussion of whether cats should be allowed to hunt birds when hungry for meat. (They shouldn’t). Attempts to demonstrate the ability of animals to be engaged political actors stretch credulity despite the best efforts of the authors.

Such moments stand in tension with the general argument for animal citizenship at the heart of the book, which is remarkably difficult to punch serious holes in. It’s a deliciously contentious thesis. The argumentative weight placed on difficult and potentially offensive comparisons between domestic animals and the seriously disabled is suppressed. And many radical claims about the necessity of inviolable animal rights are brushed over fairly quickly in order to get to the main task of moving the animal rights debate from ethics to politics. But Zoopolis successfully demonstrates the benefits of such a move and will force liberal political theorists to look much harder at the boundaries of citizenship.

That said, I was slightly disappointed when they admitted that ‘effective political representation of domesticated animals […] will not be through extending the vote […] since animals are not capable of understanding the political platforms of different candidates or political parties’. A pity – for we could often say the same about ourselves.

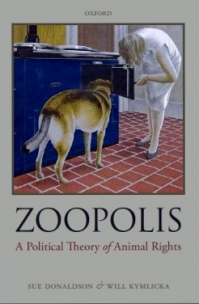

Zoopolis. By Sue Donaldson and Will Kymlicka. Oxford University Press; 264 pages, £18.99 at Blackwells.

Daniel Hutton Ferris is a MPhil student in Political Theory at Oxford University. This review is cross-posted from his new blog, Political Theory Bits.

2 Comments

More severe punishment needed, for animal cruelty to animals.

Action is needed now.