Many believe that the EU referendum has been called only to enable David Cameron to appease the Eurosceptics within his own party. This is debatable on numerous grounds. But what is certain is the eventuality that many Conservatives, including possibly some Cabinet ministers, will be joining the campaigns to get Britain out of the EU.

For over a quarter of a century the issue of Britain’s role in Europe has been one of the most significant divisions within the Parliamentary Conservative Party (PCP). The European issue has been a reliable source of problems for the party leadership over the years. It has led to many rebellions, numerous defections, the downfall of Thatcher, and partly accounts for the Conservatives’ landslide defeat in 1997.[1]

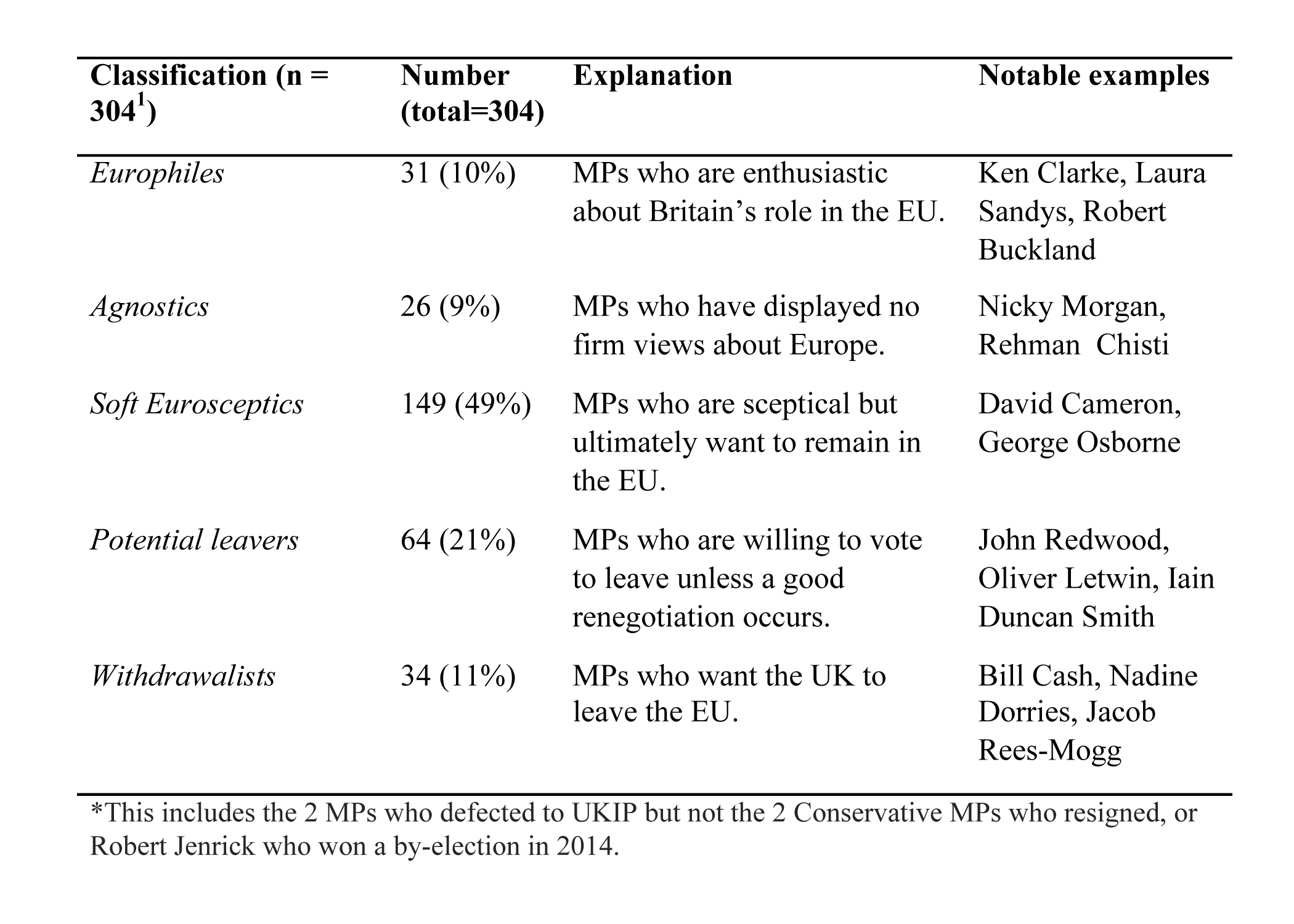

But what is the scale of Euroscepticism within the PCP today? How have modern day Conservative MPs formed their views on Europe? Can the Eurosceptics be persuaded to support the “in” campaigns? For my research, I have created a dataset of Conservative MPs (from the 2010 Parliament) that gives each MP a score according to their views on Europe. These scores were then used to perform regression analyses to investigate why Tory MPs hold differing views on Europe.

Here are some interesting findings Euroscepticism within the PCP.

When considering the extent of Euroscepticism it is important to note that it is not a binary concept. There are different degrees of Euroscepticism. For instance, there are hard Eurosceptics who want either a radically reformed relationship with the EU or for Britain to leave altogether. And there are soft Eurosceptics who are sceptical about certain aspects of the EU. They tend to not want any further integration, but ultimately want the UK to remain in the EU.[2]

For my research into the 2010-2015 PCP I categorised MPs into five categories regarding to their views on Europe.[3] I categorised each MP based on numerous sources such as their Parliamentary voting record, signing of Early Day Motions, memberships of groups such as Better Off Out or the pro-EU European Mainstream, and speeches.

The numbers suggest that around a third of the 2010 party was willing recommend Brexit.

But things changed again in 2015. Europhiles and moderate Eurosceptics were overrepresented amongst those standing down. And the new intake of Conservative MPs included many hard Eurosceptics, such as James Cleverly. Therefore it is highly likely that much more than a third of the 2015 party could be prepared to join the campaigns to leave the EU.

What makes a Eurosceptic?

The above classification of MPs then formed the basis of the ordinal logistic regression analyses[5] used to determine common traits among the out camp.

Indeed the results suggest that there are certain political and demographic characteristics that have a statistically significant association with differing level of Euroscepticism.

Conservative MPs with higher levels of Euroscepticism tend to be:

- Male

- State educated

- Have previous military experience

- Represent a constituency with either:

- Higher levels of unemployment relative to other Conservative MPs;

- Or high levels of retired persons

- Oppose abortion, three-parent embryos, and gay marriage

- Support the death penalty

These last two points mean that hard Eurosceptics are usually associated with what the media call “the Tory right”.

Meanwhile there are certain characteristics associated with lower levels of Euroscepticism. These MPs tend to have:

- Previous career experience in either the legal or agricultural sectors

- Represent constituencies with high levels of employment

- Many years of experience serving in Parliament

Explaining particular positions on Europe

The results show that there are several factors that explain why Conservative MPs adopt particular positions on Europe.

For a start, a nationalist ideology appears to be central to much Conservative Euroscepticism. The data suggests this in three principal ways. Firstly, nationalism is the most likely cause of the relationship between social conservatism and Euroscepticism, and research in political science and political psychology have established a link between social conservative and nationalist attitudes.[6]

Secondly, the connection between military service and Euroscepticism may also be caused by nationalism. It is reasonable to conclude that those who have served in the military will have a greater attachment to nationhood and to Britain. A heightened sense of national attachment could mean that ex-military MPs are more likely to oppose the EU impinging on UK sovereignty.

Thirdly, the gender gap in Euroscepticism could be explained by nationalism too. Electoral and polling evidence from across Europe suggests that women are less likely to be attracted by identity politics and nationalism. For instance, men are much more likely to support Eurosceptic parties such as UKIP and national independence movements such as those in Scotland or Catalonia.[7]

Electoral factors also appear to affect an MP’s level of Euroscepticism. The above results suggest that different constituency demographics particularly levels of employment and retired persons are associated with differing positions on Europe. This suggests that either MPs are reacting to electoral demand when adopting attitudes to Europe, or local electorates are being selective about which Conservative candidates they elect, or both.

Self-interest is another factor. For example, MPs with an agricultural background are less Eurosceptic, as agricultural interests are likely to lose out from Brexit because of a loss of CAP payments and EU migrant labour.

Finally, the results suggest that an MP’s social and career background influence their position on Europe. MPs with more privileged backgrounds—for example those who have been privately educated or ex-lawyers—are more Europhile than other Conservative MPs. This relationship does not lend itself to any obvious explanations and therefore I am keen to investigate this further in my future research

Summary and continuing research

The above results have suggested that there are multiple causes that explain why Conservative MPs adopt Eurosceptic positions. The causes identified suggests that any reform package that Cameron can achieve is unlikely to change the opinions of his backbenchers.

If Eurosceptics are motivated by nationalism it is likely that fundamental reform of the EU would be required to persuade MPs to support staying in the EU. A fundamental reform of the EU would necessitate treaty change which is unlikely within the timeframe of the referendum.

If Eurosceptics are motivated by electoral pressures it means that an electorally popular reform package will be needed to persuade Tory MPs to join the “in” campaign. However, an electorally popular reform package is unlikely as this would require measures to reduce EU immigration (the most salient issues associated with the EU) which would be met with opposition from member states seeking to preserve the principal of free movement.

Therefore it is likely that Cameron will face a substantial element of his party campaigning to leave. The big question for the future of party is whether the EU referendum will end the perennial Tory divisions on Europe.

Bibliography

Baker D , Gamble, A., Seawright, D. & Bull, K. (1999) “MPs and Europe: Enthusiasm, circumspection or outright scepticism?”, British Elections & Parties Review, 9:1, 171-18

Cowley, P. (2000) “British Parliamentarians and European integration: A Re-examination of the MPP Data” Party Politics, Vol. 6. No.4 pp.463-472

Crowson, NJ (2007) The Conservative Party and European Integration since 1945: At the Heart of Europe? (Abingdon: Routledge)

Forster, A. (2002) Euroscepticism in contemporary British politics: opposition to Europe in the British Conservative and Labour parties since 1945 (London: Routledge)

Heppell, T. (2013), Cameron and Liberal Conservatism: Attitudes within the Parliamentary Conservative Party and Conservative Ministers. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, Vol. 15 Pp. 340–361

Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2009). A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39, pp 1-23

Lynch, P. and Whitaker, R. (2013), “Where There is Discord, Can They Bring Harmony? Managing Intra-party Dissent on European Integration in the Conservative Party”. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, Vol. 15 PP. 317–339

Taggart, P. and Szczerbiak, A. (2008) “Opposing Europe? Three Patterns of Party Competition over Europe” in A. Szczerbiak and P. Taggart Opposing Europe: The Comparative Party Politics of Euroscepticism (vol. 1) (Oxford: Oxford University Press), pp. 348-63

Turner (2000) The Tories and Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press:)

[1] For background reading on the history of Conservativism and Euroscepticism, see Turner (2000); Forster (2002); Crowson (2007).

[2] For a definition and discussion of hard and soft Euroscepticism see Taggart and Szczerbiak (2008). See Heppell (2013) for a discussion of hard and soft-Eurosceptism within the Conservative party.

[3] The classification scheme I used has been adapted from Heppell (2013).

[4] This includes the 2 MPs who defected to UKIP but not the 2 Conservative MPs who resigned, or Robert Jenrick who won a by-election in 2014.

[5] The dependent variable was an ordinal measure ranging from 1 to 5 with 1 being “Europhile” and 5 being “withdrawalist”.

[6] On the political science literature see: Hooghe and Marks (2009). On the political psychology literature see: Smith et al (2011)

[7] On UKIP see Ford and Godwin (2014). On independence movements see Dunt (2014).