For the last two decades, observers and scholars of Latin American politics have wondered about the electoral fate of the left. Some analysts in particular have highlighted how the end of the ‘Pink-tide’ precipitated the comeback of right-of-centre governments across the region. But in this regard, Mexico has been running in dissonance to its regional counterparts. The right-of-centre parties Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) and then the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) occupied the executive office from 2000 to 2018 while most Latin American countries turned to either a radical or a reformist left.

Now, however, left-of-centre Andres Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) and his National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) hold the Mexican presidency. To delineate what the future might hold for AMLO, we can look to the previous experience of the left in another large, federal, multi-party presidential Latin American republic: Brazil.

Once a prominent and radical union Leader, the three-time Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) candidate, Lula da Silva, served two terms in office from 2003 to 2010. With a mix of redistributive social policies and an orthodox macro-economic stance, Lula managed to leave office with a record high personal approval rating of over 80%. Riding Lula’s coattails, PT’s Dilma Rousseff remained in office until late 2016.

Fast-forward to 2019 and the landscape of Brazilian politics couldn’t be more different. Amidst increasing polarization, Rousseff’s impeachment, Michel Temer’s arrest and Lula’s detention and later release stand out as critical moments. The apex of this political shake-up is, of course, the successful presidential bid of the controversial far-right Jair Bolsonaro.

What happened? Brazilianists have pointed towards corruption scandals, drug-related violence and economic recession as the main culprits. This complex matrix of problems boosted not only a dissatisfaction with the ‘political system’, but also a rather more specific rejection of PT-politics as David Samuels and Cesar Zucco contend. It could be argued then, that the debacle of the Brazilian left was influenced to a great extent by the significant rise of antipetismo — an antipathy towards the PT which overrides most if not all other political preferences. In contemporary Brazil, antipestismo emerged as a new dominant cleavage in the electoral arena.

In Mexico, the first twenty years of the democratic experience have been marred by violence and a dwindling economic performance. After an overwhelming victory in 2018, MORENA and the left-of-centre government of Andres Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) have had some symbolic victories, but with a poor economic performance and violence still on the rise, after 14 months in office, pundits have started to seriously question the capacity of the tabasqueño leader to deliver the promised fourth transformation of the republic.

Given the PRI’s long-standing hegemonic position in the Mexican political arena, dissatisfaction with ‘the system’ was usually expressed as an anti-PRI sentiment. Even after the 2000 transition, the PAN failed to successfully distance itself from the traditional PRI-style politicking. Indeed, AMLO’s road to the presidency was paved by this failure and facilitated by his consequent success in meshing systemic dissatisfaction with rejection of the PRI+PAN (PRIAN) political model.

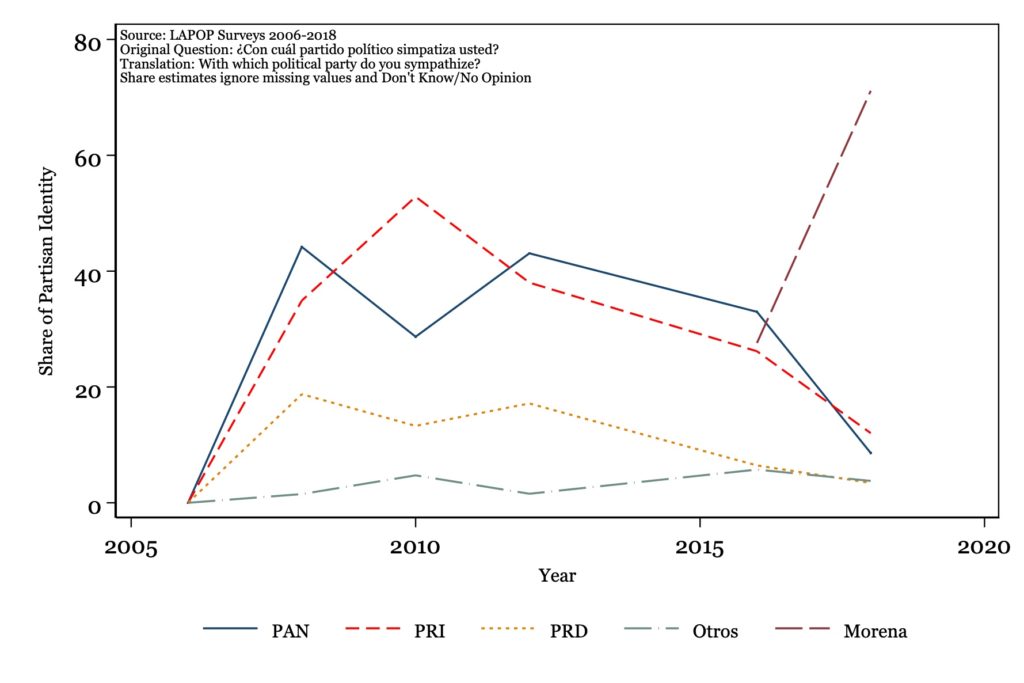

Using survey data from the ‘Latin American Public Opinion Project’ (LAPOP), Figure 1 shows the trends in partisan identities for the major Mexican political parties in the last 15 years. Two facts stand out. First, the steep and early decline of individuals with an affinity for the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD), which, up until 2016, was the only electorally competitive leftist party in Mexico.

More importantly, however, the graph also shows that for the past decade, Mexicans have detached themselves from parties. With the exception of MORENA, all political organizations have experienced an overall decline in partisanship. To put this into perspective, by 2018 the share of Mexicans expressing an affinity for AMLO’s party was roughly three times that of those identifying with the rest of the parties combined. Under this light, Lopez Obrador’s electoral victory seems almost inevitable.

While it might be too soon to wonder about the next presidential bid, the 2021 mid-term elections will be the first serious litmus test of the current administration. While the opposition in Mexico is in complete disarray, the antipetista Brazilian experience highlights that a counterbalancing force may emerge, not from the positive or proactive role of alternative parties, but rather from a rejection of lopezobradorismo. Are there any signs of an emerging anti-AMLO movement or coalition?

I’d argue that there are indeed worrying signs within the Mexican electorate even if we put aside the potential for a crisis —caused by either continued economic stagnation or a major political scandal— and acknowledge the impending internal struggle for the party’s leadership and candidate nominations. Simply put, a trend towards increased political awareness mixed with the continued detachment of partisan identification is cause for concern.

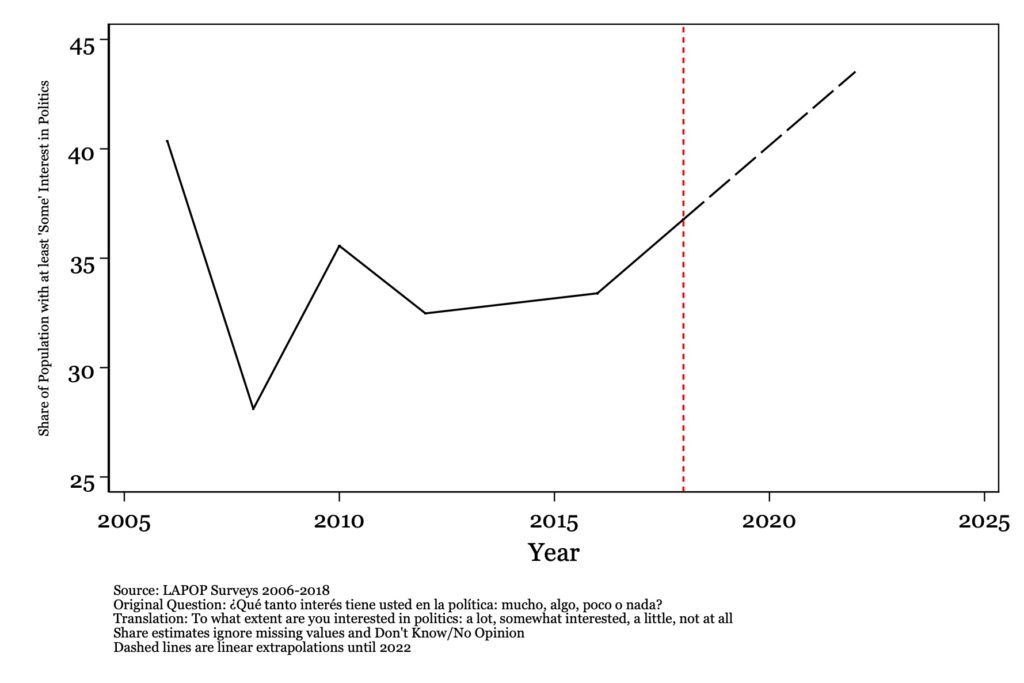

Figure 2 displays the share of the population with at least ‘some’ interest in politics since 2006. The solid line shows that over the past decade this number has oscillated between 30% and 40%. Nonetheless, using a linear extrapolation, political interest is predicted to increase in the next couple of years across the population. There are three plausible interpretations for this increase: a) it is a natural and expected occurrence given that the country is en route to the next electoral round; b) it reflects the involvement of a younger and recently enfranchised generation of voters; or as I contend c) it is a symptom of increased polarization. As the electorate perceives that the stakes of electoral outcomes go up, they are more observant of political and governmental dynamics.

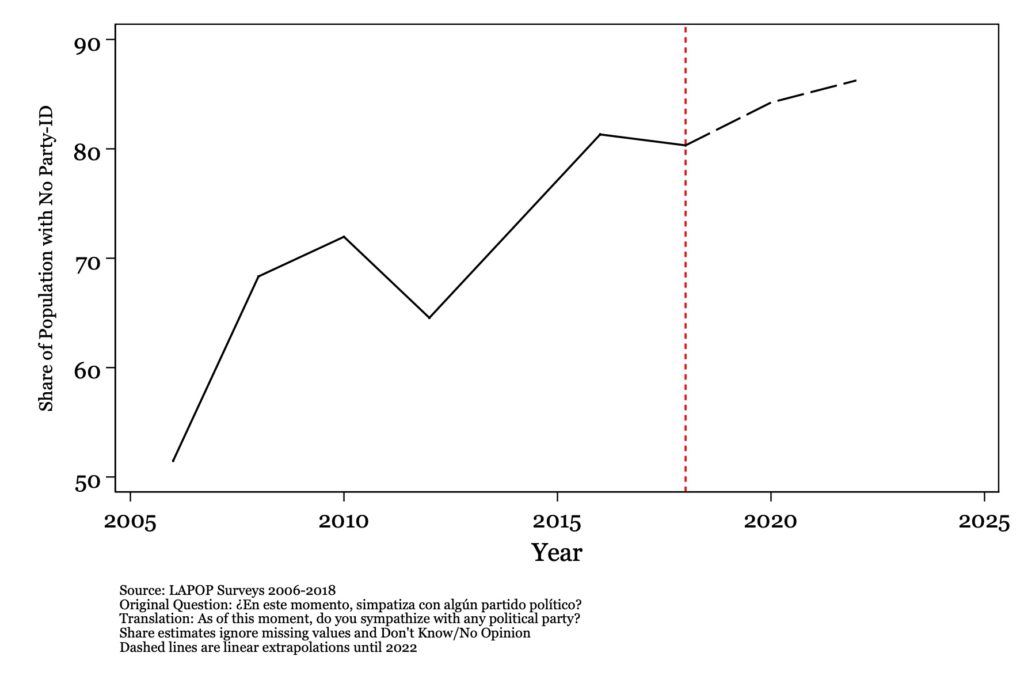

Paradoxically, this polarization-driven trend in political interest has been concomitant to a detachment of partisan identities. Contrary to what Torben Iversen and David Soskice (2015) posit for advanced industrial democracies, in Brazil and Mexico polarization has boosted a ‘washing out’ of the affinities that connect individuals to political parties. Figure 3 shows that the share of the Mexican population that do not feel sympathy for any given party has been on the rise for the last 15 years, reaching roughly 80% by 2018, and projected to be 88% by 2022.

In and of themselves, polarization and increased political awareness are not necessarily problematic. Combined with a dramatic washing out of partisan identities, however, the combo could prove severely challenging not only to AMLO, but to Mexican democracy more broadly.

AMLO has veered and manoeuvred around challenges and criticism by focusing on his anti-corruption crusade, setting the public agenda via his daily morning conferences. So far, if not successful, this strategy has at least proven sufficient, as it configures a Kafkaesque public sphere in which problems are vented and governmental attention is granted. The continued spike in femicides and the recent feminists protests in Mexico City show, however, that this approach might have an expiry date. With five years to go, AMLO’s anti-corruption narrative could prove insufficient as a long-term strategy.

Will AMLO and Morena be able to sustain the narrative of ‘real political change’ and continue to electorally benefit from anti-PRIAN sentiment? Or will an overriding disaffection with party politics and ‘the system’ bypass all major electoral forces in Mexico to overtake even AMLO himself?

In this scenario, the past and present discussion of Brazilian electoral realignment —ultimately catalysed by Bolsonaro— should echo a warning in the halls of parties’ headquarters, San Lazaro (Congress) and Palacio Nacional. The risks of extremism are apparent, not only in the South American cone, but across other major democracies in the West.