Most people in separatist-held areas of Donbas prefer reintegration with Ukraine – new survey

With renewed negotiations to end the conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas region on the horizon, the views of those people most affected by the war – the residents of eastern Ukraine – should be taken into account. Russia insists that the people living in areas of the Donbas currently controlled by separatists, who it supports, do not what to reintegrate with Ukraine. But two surveys I carried out in the Donbas in 2016 and 2019, revealed that a majority of those we surveyed in areas not controlled by the government would prefer to be part of the Ukranian state. The war in the Donbas started more than five years ago and has cost in excess of 13,000 lives. At least 1.4m …

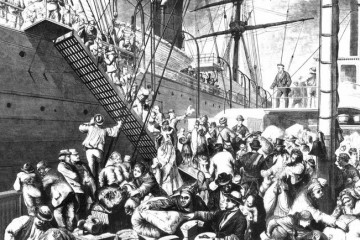

Writing home: how German immigrants found their place in the US

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. The hysterical anti-migrant and anti-refugee rhetoric from the Republican candidates in the US presidential race has reached a fever pitch lately, with Donald Trump leading the charge. From advocating the building of a wall on the Mexican border to calling for Muslims to be banned from entering the US, he has taken some positions on “outsiders” that would make some of Europe’s staunchest right-wing populists blush. But Trump could benefit from a little reflection on his own background. He himself is the grandson of a German immigrant, Friedrich Drumpf, who came to the US in 1885 – one of a great many Germans who settled in American society and helped make it what it …

Building a federal Ukraine?

The idea of a remaking of Ukraine’s constitutional order along federal lines is beginning to gain traction. On March 18, Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk reached out to Russophones in the eastern and southern regions, announcing that “new measures linked to decentralization of power will be reflected in a new constitution.” Senior U.S. administration officials have encouraged the Ukrainian leadership to consider constitutional reform along federal lines.

On March 17, the Russian Foreign Ministry proposed the establishment of an international “support group” to manage the crisis. The list of items that Russia wants to be the basis for negotiation in Ukraine includes a new federal structure for Ukraine and the recognition of Russian as a second language.

Until recently the federal idea was an anathema among the greater part of Ukraine’s political elite. As a constitutional form it was largely rejected in the 1990s, partly as a negative reaction to the experience of Soviet federalism, and partly from fear of its centrifugal potential for splitting the country along ethnolinguistic fault lines.

Crimean autonomy: A viable alternative to war?

The issue of Crimean separatism is not new. In the early post-Soviet period it became one of the biggest challenges newly independent Ukraine had to manage. A closer look at the events of the early 1990s and the concept of Crimean autonomy helps to put current events in perspective and points to an alternative to war. A history of fractious multi-ethnicity, a legacy of autonomy experiments, a Soviet-era transfer from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954, a center-periphery struggle in Ukraine, economic dependence, the tense relationship between Ukraine and Russia, and readily available military resources (in the form of the Black Sea Fleet) account for the complexity of the ‘Crimea question.’ Separatism peaked in 1992-1994, and internal and …

Who cares about Transnistria? Linkage and Leverage: External actors and conflicts in the post-Soviet space

The colour revolutions in Georgia (“Rose” 2003) and Ukraine (“Orange”, 2004) seemed to promise that countries on the North and East of the Black Sea would shake off their “post-Soviet” label and take a firm and unwavering road towards Europe and the US. Perhaps the states of Central Asia would choose a similar route. Russia would have to take a back seat. A resurgent Russia under Putin has destroyed much of this myth, not least because of Russia’s involvement in the de facto states which have arisen from conflicts: South Ossetia and Abkhazia (Georgia), Nagorno-Karabakh (Armenia/Azerbaijan) and Transnistria (Moldova). Russian influence after 200 years of empire runs deep, but local factors also have a bearing; the EU and US have not applied sufficient drive or resources to the region, or to the conflicts, to balance or check Russia.