Nurture and nature: education, blood and nationality

On the 28th of October 1940 the Greek government rejected Benito Mussolini’s ultimatum demanding that Axis forces were given free entrance from neighbouring Albania and allowed to occupy strategic locations around the country. After the war, this momentous event in the history of modern Greece – popularly known as the No Day – became a national holiday, celebrated annually with impressive military and student parades.

Fourteen years ago, one such parade had to take place in a town near Thessaloniki. As a tradition, the best student in the local high school was expected to bear the Greek flag. The best student, though, was not Greek. He was an Albanian immigrant.

Pupils, parents and citizens throughout Greece rose in anger: despite his achievement, how could a non-Greek, an alien, a non-citizen at that, be allowed to carry the national colours? The government, the main political parties and the teachers’ union stood behind the excellent Albanian student but the boy responded to the growing commotion by choosing to step aside, allowing a Greek pupil to carry the flag.

Three years later, the same Albanian – having now distinguished himself as the best graduating student of his school – was again elected to bear the colours in the Greek national holiday parade. The public outcry, in this instance, grew even wider and sharper than earlier. The young man, for a second time, decided not to accept the honour but pass it on to a native schoolmate instead.

The volcanic public discourse surrounding these events had nationality, citizenship and ethnic origin at its centre. Blood, heredity, and even DNA, became salient elements of the debate – pitted against the qualities and achievements of the person, his or her social integration, active participation in and contribution to the Greek scheme of life. ‘What makes one truly Greek: one’s Hellenic outlook, behaviour and genuine belief in Greekness, one’s abilities and success in Greek society and/or one’s historical roots and genetic ancestry?’ was a question resounding loudly across the country and the region. Is it nature or nurture, a cocktail of the two, or perhaps something greater than that, which makes us genuine sons and daughters of a country, a nation or a people?

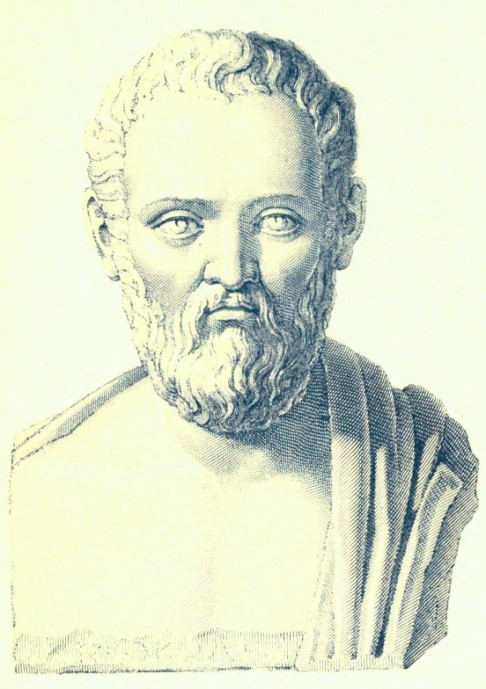

The perennial echo of this problem was picked up by the then president of the Greek Republic who, in defence of the Albanian student, quoted a line from a famous work by the great Athenian rhetorician Isocrates. “[Athens]”, the ancient man of letters writes in his Panegyricus, “has brought it about that the name Hellenes suggests no longer a race but an intelligence, and that the title Hellenes is applied rather to those who share our culture than to those who share a common blood”.