When Attempts to Change Institutions Fail: The Case of the Affordable Care Act

The U.S. Supreme Court’s recent decision to uphold the Affordable Care Act (ACA, also known as Obamacare) is the latest in a series of failed attempts by Republicans to repeal the law. From its passage in 2010, the ACA has been responsible for reducing the uninsured population significantly through its key provisions requiring individuals to purchase health insurance, extending coverage for individuals with pre-existing conditions, and expanding Medicaid for low-income Americans¹. Republican legal challenges to the ACA started within hours of its signing. Filed by states, associations, and individuals, several cases made it to the Supreme Court, which rejected challenges to the ACA in 2012, 2015, and, most recently, June 2021. These legal defeats coincide with other failed attempts by …

A gradual farewell? There will be no three-year transition period in Germany

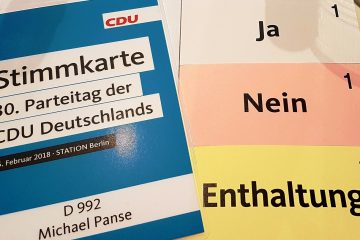

Angela Merkel’s announcement on Monday to not run again in the 2021 election has initiated a period of transition in German politics. Yet, whether this process will last until the next election, as she suggested, is questionable. German chancellor, Angela Merkel, announced on Monday that she would not be running for a fifth term in office in the next federal election in 2021 and step down as the leader of her party in December. Her statement came less than 24 hour after her Christian Democratic Union party (CDU) had lost more than 10 percent of the votes in the state election of Hesse, marking the party’s worst result in the state since 1966. The election continued an overall downturn in …

The emergence of Germany’s new right wing

While political parties promoting national liberal, conservative and Euro-sceptic positions have experienced a rise in nearly all EU member states over the past years, Germany appeared to be the last safe-haven left. However, this German exception seems to be over. Since last September the Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, AfD) has entered three regional parliaments within two weeks, living up to its success in this year’s European elections.

Supported by around 10 per cent of the voters, the AfD poses a problem to the Christian Democratic Christian Democratic Union (CDU)/Christian Social Union (CSU) and, especially, to the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP). They have to fear the establishment of a party which may challenge their dominance over Germany’s political right.

While national, liberal and conservative positions are not new to German politics, this space has mainly been covered by the CDU/CSU and FDP. Whereas national liberal and conservative parties had been an inherent part of the German party system during the imperial period and the Weimar Republic, the integration strategy of the CDU/CSU transformed German politics after World War II. By combining liberalism, conservatism and Christian democracy, the CDU/CSU had been successful in leaving only a small niche for potential competitors on the political right. This space was further reduced by the FDP, integrating national and social liberalism within the same party for the first time in German history.

Merkel’s Grand Coalition: A new chance for Germany’s social democracy

Fears over a grand coalition are again haunting Germany’s social democracy. As was the case in 2005, the new coalition is comprised of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU, together with the CSU, its Bavarian pendant) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Such a composition worries many Social Democrats given the last experience with a coalition in 2009 when the SPD vote share shrank by 12.2 per cent. Some Social Democrats are even doubtful about whether the SPD can survive another grand coalition with Angela Merkel’s CDU.

While the pessimism is understandable, it is misplaced. Another grand coalition will not necessarily produce negative consequences for Germany’s Social Democracy, for three reasons.

First and most importantly, there is no clear pattern whereby the smaller coalition partner loses in a grand coalition. The two previous grand coalitions at the national level offer mixed examples. While the last experience was surely painful for the SPD, it actually benefited from the first grand coalition from 1966 to 1969. Despite some unpopular decisions in the Social Democratic camp at the time, such as the emergency laws (Notstandsgesetze), the SPD received part of the credit from its association with several governmental accomplishments, most notably the economic policies that led to the end of Germany’s first economic recession after World War II. At the time, the SPD had managed to find the right balance between its own political autonomy and participation in the grand coalition, acquiring a reputation for pragmatism and responsibility. This was most embodied by Karl Schiller, the minister of the economy, Herbert Wehner, the party chairman, and Helmut Schmidt, the leader of the SPD’s parliamentary group. Despite being the junior partner in a grand coalition, the SPD thus succeeded in proving its worth. This, in turn, helped the Social Democrats take over as the majority party in 1969, putting an end to 20 years of Christian Democratic dominance.