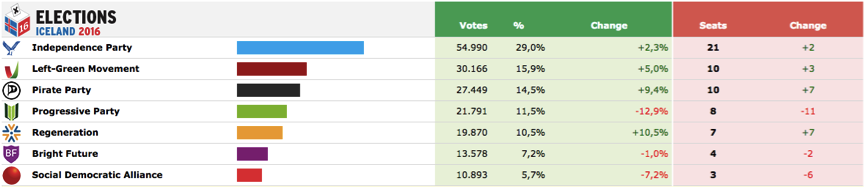

This week the Icelandic public elected a new parliament. The Independence Party was the clear winner with 29 per cent of the vote, up from the last elections 26.7 per cent. This is a good result for them, boosting their numbers by two more seats to twenty-one.

At this table shows, by contrast, it was the Progressive Party, their coalition partner, who bore the brunt of the backlash, despite Iceland’s economic recovery in the last three years. Last April, news surfaced that Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, the then prime minister, and his wife owned Wintris, an off-shore company that held debt from failed Icelandic banks – a fact he failed to disclose upon entering parliament in 2009. This caused widespread public outrage. Images from the sea of citizens protesting against their Prime Minister in front of the Icelandic parliament went viral and became a sign of Iceland’s invested civil society and its dissatisfaction with members of the political elite.

With him out of the way, now it was time for his party to suffer. Support for the Progressive Party fell by more than half compared to the previous election, from 24.43 per cent in 2013 to 11.5 per cent this year. The party lost more than half of its MPs. Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, the replacement prime minister since April has also resigned, having failed to convincingly distance the party from Gunnlaugsson’s transgressions.

The dramatic decrease in popular support for the Progressive Party may not be in itself surprising. But the boost for the Independence Party was not expected. Bjarni Benediktsson, the party leader and former Finance and Economics Minister, also had a stake in an offshore investment company in the Seychelles. But unlike Mr Gunnlaugsson he did not resign, despite 69 per cent of the population calling for his immediate resignation back in April.

Benediktsson managed to election victory on the back of repeated emphasis on the necessity to continue Iceland’s road of economic recovery. And his previous experience as Economics and Finance Minister helped. So did the economic numbers. There are clear signs that Iceland is recovering from the 2008 financial crisis in 2008 and the subsequent collapse of its banks. Iceland’s GDP is back to pre-crisis level and continues to grow. Unemployment is only around three per cent. The government even stated that there are prospects for ending capital controls, in place since the crisis, although the latter has been promised before.

What happened? The results give the impression that previous Progressive Party supporters switched allegiance to the Independence Party, also on the centre-right, to support the continuation of the government’s economic course. In total the overall support for the centre-right coalition government of Independence and Progressive Party remained at approximately 51 per cent between the 2013 and 2016 elections (if one include support for the Viðreisn party in 2016; for more on that, see below). While the overall percentages did not change, the composition of votes for individual parties changed dramatically. The Progressive Party lost 12.9 per cent of its votes between 2013 and 2016, while the Independence Part gained 2.3 and Viðreisn 10.5 per cent.

The Role of EU Membership in the Election Campaign

But dodgy dealings and the economic recovery were no the only factors. The EU also loomed large. Iceland applied to join union in 2009, with negotiations officially starting in 2010. However, in 2015 the centre-right government withdrew Iceland’s application, restarted a fight between pro-EU and Eurosceptic parties.

If it were not for the EU, the Independence Party’s gains would have been far larger. Viðreisn, a new pro-EU party, was founded following a rift among the Progressives just this past May. It received 7 seats and 10.5 per cent of the public vote.

Viðreisn now has a big part to play in coalition negotiations to form a new government, requiring 32 of the 63 seats. As it stands, the Eurosceptic centre-right camp – made up of the Independence Party and the Progressive Party—is just shy, holding 29 seats. The left bloc—comprising of the Left-Green Party, the Pirates (who also had a good election), Bright Future and the Social Democrats – hold 27 seats.

This means that Viðreisn – socially liberal, pro-free trade and pro-EU – needs to make a decision if it wants to join a Eurosceptic coalition or a potentially unstable collation of the left.

What should the do? It seems that EU membership will be a central discussion point in the upcoming negotiations. And it is essential for Viðreisn to push through a clear pro-EU membership policy. This gives it a central issue to distinguish itself from the Independence and Progressive parties. But demanding an immediate referendum on joining the EU would be premature. A poll in March last year highlighted that 71 per cent of the Icelandic population opposed Icelandic membership in the European Union. So it must be pro-EU, and in it for the long haul.

The other option is to join a liberal-left bloc. Despite the uncertainties, this looks more ideologically permissible since its EU stance would not offend its coalition partners nearly as much. Some would support it. Either way, it looks like Iceland’s Europhile minnows could emerge as the biggest winner of all.