It is a period of civil war. Rebel politicians, striking from hidden Westminster offices, have won their first victory against the evil Brexiteer Prime Minister. During the battle, Rebel MPs manage to steal control of the Commons…

The so-called “rebel alliance” of pro-EU MPs secured an important victory on September 4 of this year in their quest to prevent a no-deal Brexit: parliament passed the Benn-Burt Bill, which requires Prime Minister Boris Johnson to seek a four-month extension of Article 50 if parliament has not agreed to a no-deal Brexit or a withdrawal agreement by October 19. When the result of the vote was announced, protestors outside of the House of Commons, celebrated by playing the Star Wars theme tune.

This calls for a closer look at the effect that Star Wars has had on Brexit debates. Studying the effect that pop culture references like “rebel alliance” have on real-world political events has become a burgeoning research topic in International Relations. Scholars have identified enabling, disabling and neutralizing effects of popular culture on political debates. Popular culture sometimes enables communication as it simplifies and provides metaphorical strength,[1] but it can also disable policy-makers, as pop culture references can lead to trivialization and ridicule.[2] As I have shown elsewhere, widespread use can turn pop culture references into descriptive short-hands, and thus have a neutralizing effect. We can see most of these effects in the Brexit debate, as I will show in this blogpost, as well as an additional effect that scholars have not identified before: a motivating effect.

Throughout the Brexit debate, the media or politicians have referred to different fractions as a “rebel alliance”,[3] but since the end of 2016, when Theresa May’s plans for Brexit became more concrete, this Star Wars reference has become a short-hand for the loose alliance of MPs in Westminster who are trying to prevent (a hard) Brexit.[4]

The term “rebel alliance” leads to positive associations with Star Wars heroes such as Obi-Wan Kenobi, Han Solo, Luke Skywalker and Princess/General Leia Organa and their fight for democracy and against the violence and oppression of the totalitarian Empire and its Death Stars. The name communicates that there is a rebellion, but also that the members of the “rebel alliance” are the goodies who put their (political) lives on the line for a noble cause. We can see several examples of decision-makers or politicians tapping into this enabling effect of popular culture to lend metaphorical strength to their message.

For example, on December 14, 2017, after the rebel alliance voted through an amendment to Theresa May’s Withdrawal Bill that mandated a meaningful vote on Brexit, The National illustrated this defeat with a front-page depicting the Star Wars Rebel Alliance standing up to a rather Imperial Theresa May.

The Liberal Democrats 2017 candidate for Mayor of the West of England, Stephen Williams, was even more explicit. As the mayoral elections took place on May the Fourth (or “May the Fourth be with you”- day, as Star Wars fans like to call it), Williams repeatedly referenced Star Wars. The Dark Side of the Force represent the bad guys in Star Wars, while the last sentence, is a famous Star Wars quote:

“The Liberal Democrats are the only party fighting against the Dark Side to protect the region’s economy from a Hard Brexit and we are the only party that will fight for a Britain that is open, tolerant and united. We believe in the politics of hope rather than the politics of fear. Fear leads to anger, anger leads to hate, hate leads to suffering.”

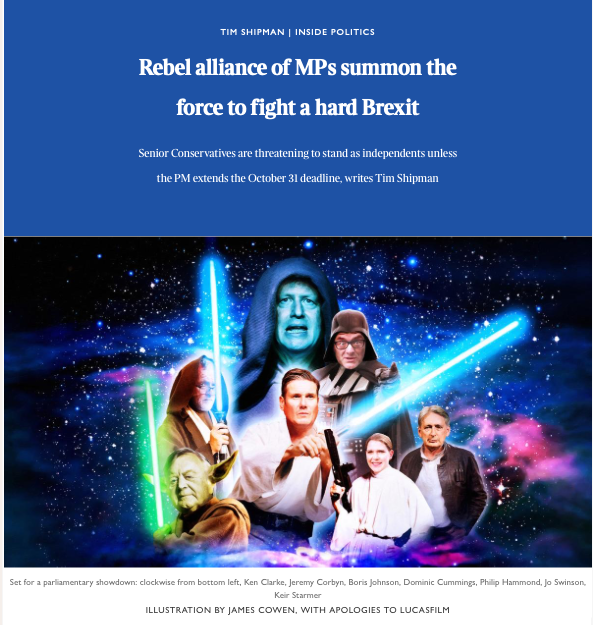

As the referendum result indicated, Britain is split on Brexit. So, it comes as no surprise that there has been some controversy around who the members of the “rebel alliance” really are. When the Times published the following illustration, a reader wrote a letter to the editor, saying “your artist surely lives in a galaxy far, far way: the characters are the wrong way round. The Brexiteers are freedom fighters liberating the British people from the clutches of the evil EU empire: it is the remainers who are on the dark side…”

As we can see in these examples, the use of pop culture references in speeches, illustrations and in writing often comes with a touch of humour or mockery. Thus, pop culture reference can have a disabling effect by poking fun or ridicule at opponents. During the Brexit referendum campaign, David Cameron tried to use the “rebel alliance” moniker in that way, when he said about leading Brexiteers on The Andrew Marr Show that “somebody will try and paint it as the establishment against you know the sort of the rebel alliance” but also that “you don’t get much more Establishment than the Lord Chancellor and the Leader of the House of Commons.”

A search of the terms “rebel alliance” and “Brexit” in UK national newspapers[5] reveals, however, that neither the enabling nor disabling effects of popular culture were most prevalent. Instead, the term “rebel alliance” is mainly used as a descriptive short-hand to refer to the pro-EU MPs in Westminster. Matter-of-fact sentences such as “to prevent Eurosceptics tearing up EU rights after Brexit the rebel alliance will also demand guarantees that key consumer protections….will not be overturned” reflect this. Overt Star Wars references such as “[f]or the Rebel Alliance, this could be the weak spot in the Brexit Death Star” or “’Pifflepafflewifflewaffle,’ yelled Johnson, after the defeat had been declared by Obi Wan Bercow, the Rebel Alliance’s Jedi knight” are not very common. And they are all but absent in parliamentary debates. As I observed when studying the effect that dubbing the Strategic Defense Initiative “Star Wars” had on the political debate, the widespread use of a pop culture moniker neutralizes enabling or disabling effects over time in public debate and turns them into descriptive short-hands.[6] The same seems to be going on here.

However, we can see an important, additional effect here: Supporters can use pop culture monikers to motivate and cheer themselves or their leaders on. What speaks to this motivating effect of popular culture even more is the fact that the staffers of the 21 Tory rebels have formed their own WhatsApp group, called the “Rebel Alliance.” According to the Mirror, it comes “with a profile picture of their bosses dressed as the appropriate Star Wars characters.” This speaks to the ability of pop culture symbols to reinforce a cause and to aid group morale.

As we are gearing up for another sequel in the fight of the

rebel alliance against Brexit, I’m curious to see how Star Wars will continue to leave its mark on Brexit debates.

[1] Neumann, Iver B., and Daniel H. Nexon. ‘Introduction: Harry Potter and the Study of World Politics’. In Harry Potter and International Relations, edited by Iver B. Neumann and Daniel H. Nexon. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2006, 18.

[2] Carpenter, Charli. ‘Rethinking the Political / -Science- / Fiction Nexus: Global Policy Making and the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots’. Perspectives on Politics 14, no. 01 (March 2016): 53–69.

[3] For example, during the referendum campaign, David Cameron referred to Brexiteers as “rebel alliance”. See http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/21021603.pdf. In July 2016, when the media discussed the possibility of a leadership contest in the Labour party, anti-Corbyn MPs were described as “rebel alliance” members. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jul/13/corbyn-rivals-labour-sinking-leadership

[4] An analysis of my search results indicates this. See www.nexis.com, search terms “rebel alliance” AND “Brexit”, UK National Newspapers, timeframe: 1 January 2016 – 17 September 2019.

[5] See footnote 4.

[6] Stimmer, Anette. ‘Star Wars or Strategic Defense Initiative: What’s in a Name?’ Journal of Global Security Studies 4, no. 4 (1 October 2019): 430–47.