Angela Merkel’s announcement on Monday to not run again in the 2021 election has initiated a period of transition in German politics. Yet, whether this process will last until the next election, as she suggested, is questionable.

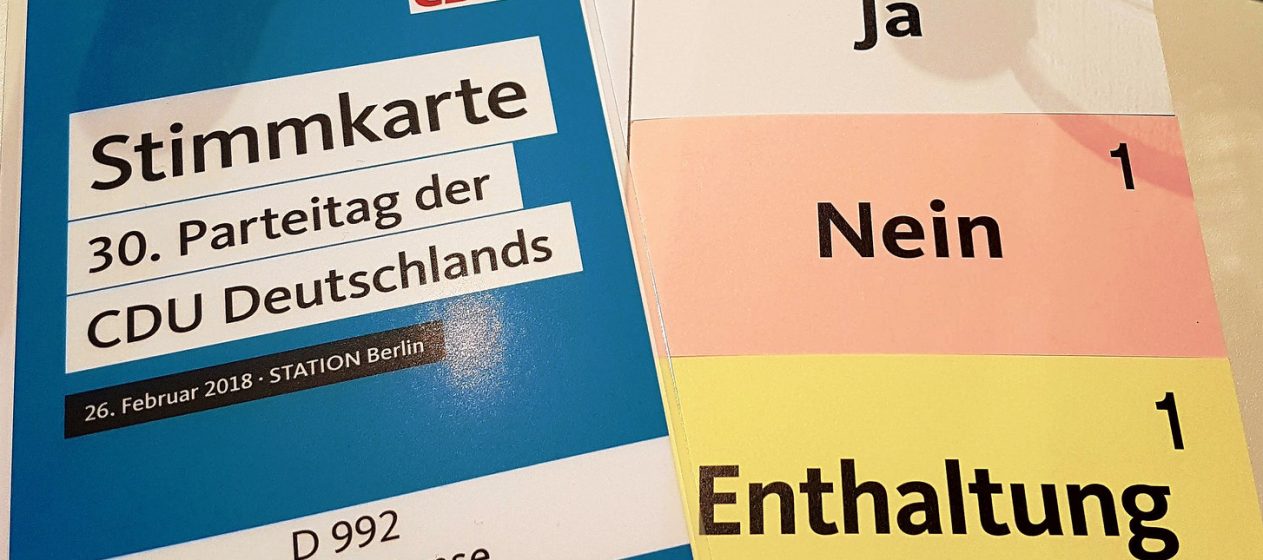

German chancellor, Angela Merkel, announced on Monday that she would not be running for a fifth term in office in the next federal election in 2021 and step down as the leader of her party in December. Her statement came less than 24 hour after her Christian Democratic Union party (CDU) had lost more than 10 percent of the votes in the state election of Hesse, marking the party’s worst result in the state since 1966. The election continued an overall downturn in popularity for the party Merkel has been leading for 18 years. After heavy losses in last year’s federal election, current polls see the Christian Democrats at around mid-20 percent – only five years after receiving over 40 percent of the votes in the 2013 election, at the peak of Merkel’s popularity. Her announced withdrawal from domestic politics in 2021 will be preceded by her resignation as party leader. The election of a new leader is scheduled to take place in December, when the CDU is holding its annual party conference.

Giving up the party leadership now but keeping the chancellorship for the time being is unlikely to be the basis for a stable government for the next three years. Looking at who is seeking to replace her as CDU leader, the deeply entrenched tradition to keep both party and executive leadership united in the same person, and the current state of the SPD, the CDU’s partner in the governing ‘grand coalition,’ make it questionable whether Merkel will indeed stay in office until 2021.

Merkel will have to work with whoever is replacing her as party leader – a task which may be almost unfeasible depending on who is going to emerge victorious. Three candidates with a serious chance of winning have already announced their intention to run.

On the one hand, this slate includes Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, who was governor of the small German state of Saarland until the beginning of this year when she became party secretary. If she wins, it will be the best scenario for Merkel. It is no secret that she and Merkel can work well together.

On the other hand, however, we have two distinct Merkel opponents. Friedrich Merz was leader of the CDU’s parliamentary group and leading figure of the party’s market-liberal wing. He had temporarily left politics after losing the power struggle against Merkel in the early 2000s.

Jens Spahn, currently minister of health, has become widely known as one of the most outspoken opponents of Merkel’s refugee policies.

A victory of either Merz or Spahn in December would establish a second political centre of gravity besides Merkel. In the likely case of political disagreements, they could easily question Merkel’s authority to make important choices given that she will be from now on a ‘lame duck’ chancellor.

Besides these practical problems of splitting the position of party leader and chancellor, the CDU’s history is telling us that this separation is unlikely to last. In 49 years of CDU-led federal government, it was only for 3.5 years in the 1960s that the party leader did not also hold at the same time the position of chancellor. The time when Konrad Adenauer had to cede the chancellorship to Ludwig Erhard while hanging on to the party leadership and the six months after Kurt Georg Kiesinger had become chancellor before also taking over the CDU leadership from Erhard are not known as the most harmonious times in CDU history. At one point, there will be an attempt to reunify both positions in the same person. And, as Merkel will not re-assume the leadership of the party, this means she will have to leave office.

How quickly this concentration of party and executive leadership will happen is also influenced by Merkel’s main coalition partner – the Social Democrats. Their situation in the recent elections is even worse than that of Merkel’s party. They lost more than half of their vote share in the recent Bavarian state election, dropped under 20 percent in their post-war stronghold of Hesse, and are currently also polling well below 20 percent at the national level. Discussions around putting an end to the unpopular coalition with Merkel’s Christian Democrats have been going on since the government was formed in early 2018. Indeed, the SPD had initially ruled out reforming the ‘grand coalition’, before protracted negotiations. The electoral disasters of the past week will not help to silence demands for an immediate withdrawal from the government.

If the SPD walks out, this would not necessarily mean new elections and an end to Angela Merkel’s time in office. Influenced by the experience of the highly instable inter-war democracy, the German constitution has imposed high barriers to remove a sitting chancellor. The so-called constructive vote of no confidence requires the endorsement of a new chancellor by a majority of the MPs in order to vote an incumbent out of office. This has only been attempted successfully once in German post-war history, at a time when coalition arithmetic was much less complicated than in the current seven-party parliament.

If the SPD walks out and Merkel loses the support of a parliamentary majority, she still would not have to resign. She could try to form a new coalition. Yet, as both the socialist Left Party and the radical right AfD are not feasible options for forming a new CDU-led coalition, Merkel would need the support of both the Greens and the liberal FDP to secure a majority. FDP-leader Christian Lindner, however, has already said that they would not join a coalition under Merkel’s leadership.

A minority government thus remains as the only option for Merkel to remain chancellor if the SPD decides to withdraw. While possible, it would mean a major departure from German post-war politics, which has been characterized by an emphasis on the importance of stable majority governments. It would also go against Merkel’s own refusal to lead a minority government after the coalition talks with the Greens and the FDP had failed earlier this year.

Merkel’s decision to step down as party leader but to remain as head of the German government has taken some pressure off her and given her own party the chance to initiate a needed process of renewal. Yet, it seems questionable whether her own party will stick to the road map which would see her serve as chancellor until the 2021 election. The CDU’s conference in December may already entail the election of one of her most outspoken opponents as her successor as party leader. Neither Merz nor Spahn are likely to accept the separation of executive and party leadership for long, which is not only highly unusual for the CDU but also comes at a time of relative governmental uncertainty.