As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine enters its second year, the Wagner Group has been expanding its Kremlin-backed footprint across the globe. In particular, the mercenary network has been deploying forces in Africa’s Sahel region, revealing how Moscow is strategically blurring the line between “anti-terror” operations, security-for-resources tradeoffs, and covert political influence. In recent months, U.S. officials have accused Wagner of exploiting resources in the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, Sudan, and beyond in an effort to fund Putin’s “war machine” in Ukraine — a charge Moscow dismissed as “anti-Russian rage”. Beyond the Ukraine crisis, however, the group’s activities and atrocities are painting a dire picture of Russia’s long-term strategy to destabilise Western relationships and gain a foothold in the African bloc.

The Sahel: A Target for Intervention

Suffering from a long history of political instability, armed conflicts, and the resulting displacement of an estimated 2.7 million people, the Sahel is acutely vulnerable to mercenary interventions. Since 2020, the region’s humanitarian crisis has escalated into successive military coups, including in Burkina Faso, Mali, Chad, and Guinea. In response to the “gross human rights violations” perpetrated by authoritarian leaders, the Biden administration terminated the countries’ free trade deals with U.S. markets. Meanwhile, Russia has exploited the security vacuum left by the West, particularly France, the Sahel’s former colonial power, which withdrew troops from CAR in 2017, Mali in August 2022, and Burkina Faso in February 2023. Amid the region’s jihadist resurgence, the Wagner Group has been making inroads, providing African regimes with security assistance, orchestrating illicit deals, and sponsoring disinformation campaigns — with grave consequences for civilians.

Since its formation in 2014 by longtime Putin-loyalist Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Wagner Group has established a record of aligning with African strongmen. In Sudan, Wagner operatives advised Omar al-Bashir, charged by the International Criminal Court (ICC) with several counts of genocide, to publicly execute protestors as a warning to civilians. Wagner-engineered disinformation campaigns have also interfered with elections in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Madagascar, Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. In CAR, President Touadéra allegedly hired the mercenary network to keep rebels out of Bangui and “defend” the country’s lucrative gold mines. Moreover, in 2021, Wagner sent four hundred mercenaries to Mali, ostensibly to combat jihadist groups, followed by arms shipments in 2022. Although the Malian government does not officially recognise Wagner’s presence, civilian casualties have risen disproportionately since the group’s arrival, echoing patterns of “anti-terror” violence against local populations in CAR, Libya, Syria, and Ukraine.

Strategic Deals: Weapons, Resources, and Lives

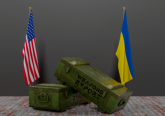

Wagner’s operations are driving vulnerable civilians into the arms of extremist groups such as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, making the Sahel a magnet for arms trafficking, exacerbated by porous borders and corrupt governance. African, European, and U.S. officials have raised alarm that the group is replicating this blueprint of atrocities in Burkina Faso — where anti-French and pro-Russian sentiment have soared in recent months — following the alleged exchange of security services for mining contracts between Moscow and Ouagadougou. The revenue of these “no strings attached” arrangements — consisting of training and weapons sales and access to valuable resources such as gold, diamonds, uranium, and oil — intends to fill Russia’s sanction-shaped hole since the start of the war.

Beyond natural resources, Wagner is also striking deals with African regimes for human resources, in the form of cannon fodder. In an effort to replace its heavy military losses, Russia is reportedly freeing African prisoners and coercing them to fight in Ukraine with minimal training, inadequate nourishment, and scant ammunition. In the CAR, dozens of prisoners — primarily identified as Union For Peace (UPC) rebels who the regime considers “terrorists” — have been recruited by Wagner as alternative sources of manpower. According to Russian security expert Mark Galeotti, enlisting African prisoners is a strategy to conceal battlefield losses and avoid conscripting Russian citizens, who remain largely uninformed by state-run media about the Kremlin’s frontline failures.

Despite its rapacious record of human rights abuses, opinions about Russia’s invasion among the African bloc appear not to have shifted significantly since February 2022. At the latest UN General Assembly resolution, which condemned Russia and called for an immediate end to the war, African countries accounted for nearly half of all abstentions. Officially, these nations are “unaligned” with both Russia and the West-backed Ukraine. Yet, many states have a friendly relationship with Moscow dating back to the Cold War, when African nationalists relied on Soviet weapons, military training, and even ideology to fight against (neo)colonialism. Speaking in early February, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov cited “European colonialism” as the enduring source for global inequities, before reiterating the Kremlin’s support for African “independence.”

How Should the West Respond?

Despite their anti-Russian rhetoric, NATO countries appear unwilling to push Moscow out of the Sahel, overlooking the region’s crucial significance as both a broader contest for access, and the central arena for African (in)stability. Recent references by Western leaders to a zero-sum competition paradoxically amplifies the historic resentment and hypocrisy that the Kremlin’s proxies are trying to exploit. While traditional approaches to combat Wagner — including the imposition of sanctions and formally listing the network as a foreign terrorist organisation — would offer a useful first step, Western leaders must address the root causes of instability in the Sahel. Greater international attention should be given to rebuilding the region’s deteriorated institutions, addressing the impacts of climate change, combatting jihadist groups, and preventing the spread of political instability to neighbouring countries.

Rather than viewing the Sahel as a chess piece in a great-power competition, the West should focus on bolstering the resilience of African states and providing diplomatic and technical support to unions such as the AU and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The Wagner Group may offer a quick fix for the leaders of African regimes, but the West has and should use its resources to help provide a long-term, regional solution.