According to a recent national survey on crime and victimisation in Brazil, more than fifty per cent of respondents reported having been robbed at least once, while 85 per cent know at least one other person who has been victim of the same crime. Latinobarómetro data from 2023 shows that 59 per cent of Brazilian respondents are worried “all the time” about becoming a crime victim. Such alarming numbers are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to crime and violence in the largest country in the Southern hemisphere.

Results from the most recent National Transport Confederation (Conferederação Brasileira do Transporte, CNT) national poll conducted in mid-January 2024 clearly indicate public safety as the major challenge to be faced by Lula da Silva in his third term. According to the CNT survey, 27.4 per cent of respondents consider public safety to be the area in which the current administration performs the worst, followed by the economy (25.4 per cent), health (22.4 per cent), tackling corruption (21 per cent) and education (12.6 per cent). In addition to public safety being at the top of this infamous list – and likely bearing the most consequences for the next elections – the general perception is that the federal government’s treatment of this issue has worsened. In a CNT survey conducted in January 2020, during Jair Bolsonairo’s first year in office, only 14.5 per cent of respondents considered public safety as one of the federal government’s worst-performing. With a “disapproval rate” on public safety almost twice as high as his predecessor at the same point during his presidential term, many political commentators have speculated that crime and violence will be Lula’s Achilles’ heel.

With important local elections set to take place in October 2024 – the first since the far-right populist Jair Bolsonaro left the presidency – the left-of-centre coalition led by Lula da Silva’s Workers’ Party (PT) must race against time to deliver public safety policies and prevent a radical right rebound. Given the severity of the public safety crisis, the current administration’s favourable economic performance may not be sufficient for nationwide electoral success in the ballot.

Given the recent appointment of former Supreme Court justice Ricardo Lewandowski as Brazil’s new Minister of Justice and Public Security, the issue is set to be at the heart of October’s upcoming midterm elections. The PT’s eventual failure to address Brazil’s public safety crisis would have significant implications for the future of the country’s democracy. Jair Bolsonaro and the Brazilian far-right will undoubtedly capitalise on the issue by emphasising the need for a strong ruler with an iron fist. Such a campaign strategy could generate widespread social and political support, spurring another round of riots like those that occurred on January 8th 2023, when thousands of far-right extremists invaded and vandalised Brazil’s National Congress.

Crimes against property, an everyday threat

The Brazilian Public Safety Annual Report 2023 (BPSA) reveals the severity of this public safety scenario. In 2022 alone, 373,225 vehicle thefts were registered in the country, eight per cent higher than in 2021. About one million cell phones were stolen in 2022, 16 per cent higher than in the previous year.

Fraud represents a league of its own. Some 1.8 million realised or attempted frauds were reported to the local authorities in 2022, 38 per cent higher than in the previous year and a fourfold increase compared to 2018. On average, 207.7 cases were registered per hour in 2022.

During the Covid-19 lockdowns, several countries witnessed a reduction in crime, Brazil included. Today, however, the incidence of crimes such as theft and robbery seems to be returning to pre-Covid levels. The steady increase in internet use during the pandemic may explain the increase in fraud, with more transactions being conducted online alongside greater exposure to phishing and other online scams.

More intentional homicides than casualties in a civil war

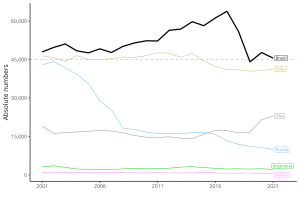

The number of violent deaths in Brazil rivals that of war-torn countries. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Brazil was the world’s leading country in absolute numbers of intentional homicides in 2021, with 45,562 registered cases, notably higher than India, which registered 41,330 cases despite having a population 6.5 times larger. 2021 was not a one-off: Brazil has registered more intentional homicides than its BRICS partners throughout the 21st century. Astonishingly, the forty-five thousand homicides in 2021 marked a significant reduction from 2017, when 63,788 Brazilians were assassinated.

Figure 1. Absolute number of intentional homicides in Brazil, 2001-2021.

Note: Numbers for Argentina, France, India, Russia, and the United States are presented for comparison. Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Elaborated by the authors.

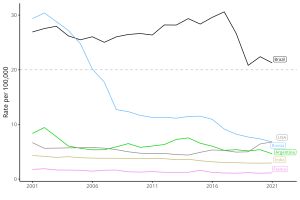

Despite a 2.4 per cent reduction in intentional homicides from 2021 to 2022, the rate of intentional homicide in Brazil remains one of the twenty highest in the world – above 20 per 100,000 inhabitants since 2001 according to the UNODC. This figure is about three times higher than Russia and the United States, five times higher than neighbouring Argentina, and twenty times higher than France.

Figure 2. Rate of intentional homicides per 100,000 in Brazil, 2001-2021.

Note: Numbers for Argentina, France, India, Russia, and the United States are presented for comparison. Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Elaborated by the authors.

Lethal violence in Brazil is akin to a civil war scenario. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, 162,390 civilians and 340,674 non-civilians were killed from the onset of the civil war in March 2011 until March 2023, totalling 613,000 dead. In Brazil, 601,716 individuals violently lost their lives between 2011-2021 according to the UNODC, while the BPSA reported 47,398 intentional homicides in 2022, 76 per cent of which were caused by firearms. Is Brazil witnessing an undeclared armed conflict?

Perceptions of unsafety in the public opinion

Recent polls capture the public’s profound feeling of insecurity. According to the Brazilian Social Survey 2023 (Pesquisa Social Brasil 2023, PESB), two-thirds of respondents believe that crime has increased in the country, and 44 per cent reported that crime has increased in their towns over the past year. Almost half of respondents (48.5 per cent) believe there is a “high” or “very high” chance of being robbed. The AmericasBarometer in 2016 documented that 71 per cent of respondents were worried “a lot” or “somewhat” about being assaulted on public transportation.

Amid a public safety crisis, most Brazilians do not have faith in the ability of the police forces to protect them. Although more than half of PESB respondents believe the police is well-intentioned (55 per cent) and competent (58.5 per cent), they also believe it is ill-equipped (52 per cent) and unprepared (52 per cent). The government is seen as providing insufficient working conditions (56 per cent) and does not pay the police forces enough (68 per cent), while eight out of ten (78 per cent) respondents believe the police lacks sufficient personnel.

Coda

Municipal elections are crucial for the formation of political alliances in Brazil as they establish grassroot support – via local political allies and campaign rallies – for national elections that are set to occur two years later. Lula da Silva’s narrow victory over Bolsonaro in 2022 by a two per cent margin signals an unprecedented importance of municipal elections in 2024, with public safety anticipated to be a core issue.

Despite his law-and-order rhetoric, Bolsonaro’s successful 2018 presidential bid was accompanied by a manifestoperfused with vague policy proposals such as “zero tolerance against crime”. It was unsurprising that his administration delivered a nothingburger of an anti-crime policy. This does not suggest, however, that public safety issues are easily addressed by other political forces. Brazil follows a growing trend in global democracies of crime being weaponised by right-wingers to attack the policy failures of progressive groups. Moreover, Brazil’s police forces – notedly the state-level militarised police, responsible for patrolling and first response – are historically suspicious of left-of-centre policies. As former policeman turned into a Workers’ Party representative Leonel Radde recently observed, “it seems I am too much of a leftist for the police, and too much of a cop for the left.” Given many police officers’ adhesion to Bolsonarism, bridging the policy gap will not be a trivial task for Lula da Silva’s Workers Party.

Tackling public safety issues is not a singular feat but a complex process, and there are signs that the PT-led federal government is aware of the monumental challenge it faces. The administration recently launched the Celular Seguro(“safe cell phone”) app that permits mobile phone owners to quickly block and disable a robbed device, with the goal of reducing mobile phone thefts. If effective, the app may have a positive impact on public opinion, given the widespread occurrence of this crime. However, on several related policy issues, political consensus is pending. A recent presidential decree that approves public-private partnerships on the prison system and public safety reform has stirred controversies, among both the public and the current administration. Dr Silvio Almeida, The Minister of Human Rights, has argued that such a partnership might backfire the government’s anti-crime policy by empowering rather than combatting organised crime.

An overarching, long-term policy strategy – that includes urgently needed external accountability mechanisms, further civil command-and-control over the police forces, a drastic review of the mass incarceration policy and anti-drug policy, as well as a reassessment of article 144 of the Federal Constitution of Brazil (which regulates public safety affairs) – is yet to be established. Even if PT were to implement such a strategy, its effects on the party’s electoral success remain far in the realm of speculation. One thing, however, is certain. A failure to effectively and quickly address the crime threats faced by everyday citizens may leave the door open for a reinvigorated far-right who will blame “the left” for the spiral of violence. Neglecting the issue will lead to a high price – in property and in lives – to be paid.

The authors thank Dr Alberto Carlos Almeida for the permission to use the PESB 2023 data.

Note: This article reflects the views of the author and not the position of the DPIR or the University of Oxford.