In June 2021, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Mexico will face what is bound to be one of the most complex mid-term elections the country has seen in the last two decades. At stake is control of 15 (out of 32) governorships, 30 state legislatures, 1,900 municipalities and a complete renewal of the Lower Chamber of Congress. The outcome will clearly be either a punishment or a reward for the leftist administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) and the ballots cast this summer will undoubtedly make or break the second half of his presidency.

The extent to which the COVID-shock has impacted individual political preferences in Mexico remains unclear. Looking at the most recent available data to conduct an exploratory analysis of the country’s political landscape, I will argue that the terrain is set for a rightwing political shift. This conclusion comes from examining the spread of COVID in the country, the outlook of the economy and an estimation of the implications for politics and ideology.

COVID-19 and the Mexican Economy

Electoral outcomes around the world are bound to be influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic for years to come and Mexico will be no different. Nationwide, more than 1.8 million citizens have been infected with the SARS-Cov-2 virus, ranking it the third highest Latin American (LATAM) country in infections, behind only Brazil and Colombia. As of the end January 2021, more than 160 thousand COVID-related deaths have been officially registered. As shown in Table 1, Mexico is then the fourth worse hit country in the world, only behind the US, Brazil and India. If, however, we consider the epidemiological measure of ‘excess mortality’, the SARS-Cov-2 virus been more deadly only in Peru.

| Rank | Confirmed Cases | Official Death Toll | Excess Mortality |

| Latin America | 3rd | 2nd | 2nd |

| Worldwide | 13th | 4th | 2nd |

| TOTAL | 1, 861, 882 | 161, 946 | 251, 805 |

Source: Official Mexican COVID data, Our World in Data and The Economist. Consulted on Jan 20, 2021.

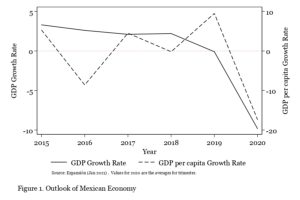

With the vaccine rolling out and lockdown measures still in place, there is hope that the health crisis will be put in check. The tragedy, however, has also severely hit the Mexican economy. At the end of 2020, a report revealed that 8 out of 10 small and medium hospitality businesses could face bankruptcy this year. Although remittances continue to flow into the country and oil prices have experienced a slight recovery after dropping to zero last year, no sector in the economy has been left unscathed by the pandemic. Figure 1 shows that the yearly growth rate of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell 10% and the rate per capita fell an even greater 17%.

While advocates contend Mexico has the best government possible in the worst circumstances imaginable, critiques have poignantly highlighted the inadequacy of AMLO’s measures. Critically, in contrast to trends elsewhere in Latin America and in Europe, AMLO’s administration has not implemented any robust policy to support businesses, retain jobs or expand social provision to assist those in need. If this continues to be the case, the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has estimated an 5% increase in extreme poverty. That is, roughly 6.3 million additional people would fall under the poverty line in the upcoming year. Relatedly, ECLAC also expects inequality to rise, making Mexico the hardest hit country economically across the region by the COVID pandemic.

Voters have felt the shock. Last year was the first in AMLO’s term in which subjective evaluations of economic prospects took a turn for the worse. Roughly 40% of the population believes the economy will get worse, while only 28% thinks it will get better. As many studies on voting suggest, voters go to the ballot with their economic interests in mind. If people do vote with their wallets in mind, AMLO and his party MORENA face a dire outlook at the ballot box this year.

Probing the Political Landscape

Given the health and economic crises, in face of the upcoming election: what does the Mexican political arena look like?I have previously argued that there were two signs for concern in the Mexican political scene going into the 2021 elections. First, I suggested that a mix of increased political awareness and partisan detachment could bypass or overcome traditional party politics. Second, borrowing from the Brazilian antipetismo experience, I predicted that in Mexico, a counterbalancing force could emerge, not from the positive or proactive role of alternative parties, but rather from a rejection of lopezobradorismo.

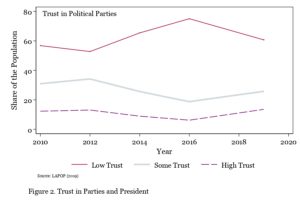

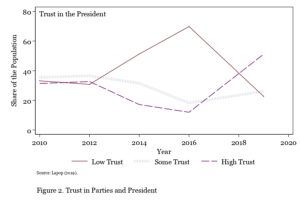

While polarization has fortunately not turned into violent radicalization, the left panel of Figure 2 shows that trust in political parties remains considerably low. Roughly 6 out of 10 Mexicans mistrust what political scientists consider the conventional channels of political engagement in representative democracies. At the same time, however, the right panel of Figure 2 shows that trust in the president is at its apogee. An underlying trust in AMLO’s persona might explain why, in spite of the health and economic situation, as of last December, 61% percent of the population still approved of AMLO.

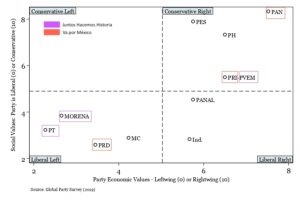

The contrasting levels of trust might give López Obrador an upper hand in June. However, the president and his party are not the sole players in town. AMLO will have to face an opposition that, through an uncanny electoral alliance, has found renewed strength. For the upcoming election, the PAN, the PRI, and the PRD —the three traditional right, centre and left-wing parties— have decided to officially join forces via the ‘Va por Mexico’ (‘This one’s for Mexico’) electoral coalition. To counter this anti-AMLO effort, MORENA, the PT and the PVEM have similarly coalesced under the banner ‘Juntos Hacemos Historia’ (‘Together we’re making history’).

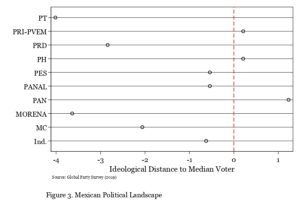

A quick glance at the top panel of Figure 3 reveals that Mexican voters face a choice between two major political alternatives with disparate ideological compositions which are highlighted in purple and red. Clearly, the PRI and the PAN are betting on attracting left-of-centre voters via the PRD while MORENA’s aims to counterbalance some of its most radical factions by joining forces with the socially conservative and rightwing PVEM.

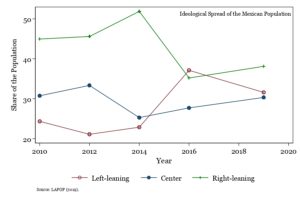

The question is which coalition will offer better electoral pay-offs. The mid-panel of Figure 3 shows the ideological spread of the Mexican population while the bottom panel shows the ideological distance between parties and voters. As of last year, we can see that roughly 40% of the population had right-leaning tendencies and that the ‘Va por México’ coalition is closer to the true sentiment of the people. MORENA and the PT are the parties farthest apart from the average ideological position of the median Mexican voter.

What’s to come?

López Obrador and MORENA thus face an uphill battle. With rampant COVID deaths and cases, a flayed economy and ideological disconnects, Mexico seems poised to experience a return to the right. Political experiences across South America have shown the ease with which Foucault’s pendulum can swing back and forth along the ideological spectrum. Can Mexico still reiterate its turn to the left as recent polling data suggests? And if it does, has the ‘Va por Mexico’ right-wing coalition missed its opportunity? Or will the right survive in states and municipalities across the country?

If MORENA’s pragmatic electoral coalition and AMLO’s charismatic appeal can trump ‘objective’ economic voting, they may retain the majority in Congress and a considerable number of governorships. This would help López Obrador smoothly navigate the upcoming 3 years and pave the way for a second left-of-centre candidate in the 2024 presidential elections. If, however, the country resolutely returns to the right — or if the ticket splits —it is less likely that progressive forces will be electorally viable in 2024 and the country would risk governmental paralysis in the midst of a crisis. Whatever the outcome, it is bound to reshape the landscape of Mexican democracy.