In earlier generations voters were spoiled for choice. Between 1832 and 1885 many had more than one vote in general elections. The British parliament contained county and borough constituencies and these, depending on size, would return two to four MPs with voters able to vote for as many candidates as there were seats to be filled. A recipe for chaos, perhaps, but there were advantages to these multi-member constituencies. For instance, the Liberals could put up a left-wing radical as well as a traditional Whig, thus broadening their appeal to the electorate. [One wonders whether such an approach could appeal to the modern Labour party]. The upshot was that electors had a choice of which MP to turn to for help, creating healthy competition for responding to constituents’ needs. The stereotypically lazy incumbent in a safe seat lost his sinecure.

On balance the nineteenth-century franchise does not need reviving. Voters had to be male, relatively rich and long-term residents. But a multi-member constituency had one advantage: it gave different communities better representation. By contrast, the single-member constituencies we have today are a creation of the boundary commissions of 1884 that worked on the principle that all constituencies should have the same number of voters. This fixation with equal constituency size upholds a vital democratic tenet of equal representation; but it also results in the confusions of the current Boundary Commission proposals. This is because in a country of sixty million people, finding coherent groupings of 74,000 electors is often impractical.

Despite the politics lurking behind it, as populations are increasingly mobile there is a constant need to shift boundaries. Communities on the borders of constituencies face the confusion of not knowing whom their MP is and the contradiction of having local government that does not match their Westminster constituency. To take a practical example, if you currently live in Nailsworth, a small town to the south of Stroud in Gloucestershire, your local authority is Stroud district council and you are in the Stroud parliamentary constituency. Under the new proposals, however, from 2020 Nailsworth will be part of the neighbouring Cotswolds constituency, but will remain in the Stroud local government district. To offer one consequence: if after 2020 you have a problem with your child’s education, or refuse collection, or any other local government issue, you might seek support from your local MP for the Cotswolds. Except the Cotswold MP has fewer connections and far less influence with Stroud district.

With boundaries due to be shifted every five years in line with population change, these cases, by no means unusual, will become frequent all over the UK. An MP who knows that certain wards may be shifted to a neighbouring seat at the next election is likely to ignore these voters whilst focusing on building her support in the new areas being added to his or her seat. For every constituency that is a coherent, recognisable community (Gloucester and Cheltenham are two good examples close to my home) there are tens, maybe hundreds that are cobbled together, lacking any identity and subject to change every five years.

We rarely discuss communities in such local terms today. People work remotely with colleagues on another side of the world; they commute over fifty miles daily in order to find affordable housing; social media makes communities exist online as much as in distinct locations. But strangely, we still insist that Britons are best represented by 600 bubbles of 74,000 voters, each returning a single individual to Westminster.

Age-old remedies

Luckily, a simple solution to these contradictions already exists: have larger multi-member constituencies and make the variable be the number of MPs, not the boundary. As an example, Britain’s counties and major cities have the merit of being both grounded in history whilst retaining distinct administrative functions and common cultures. People identify with the county or major city they inhabit. These are also large enough that it is unlikely that redrawing boundaries will become necessary in the future. As the population expands or contracts, the number of MPs can be adapted accordingly. And multi-member constituencies could easily be adapted to proportional voting systems in the future if the population wanted it. For the very largest counties and cities a subdivision could be made, rather like the historic Ridings of Yorkshire. And large constituencies returning five to ten MPs would give smaller parties a chance to mitigate the “wasted votes” syndrome felt by UKIP, the Greens – even the Liberal Democrats.

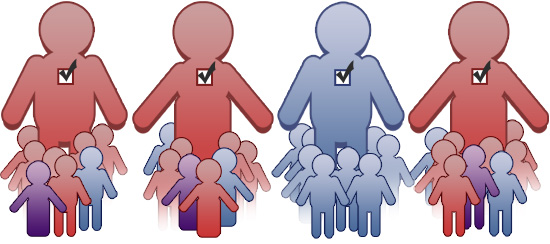

Let’s imagine what one of these new constituencies could look like. The historic county of Gloucestershire is made up of seven distinct constituencies.[1] Rather than have a five-yearly exercise of tinkering with boundaries, there should simply be seven MPs for the whole county. Were an individual Gloucestershire voter given up to seven votes to distribute as s/he saw fit, it is of course impossible to know whether this would lead to seven Conservative MPs returned (as was the case in the 2015 election), or a mixture of parties (in 2005 the seats were split three Conservative, two Labour and two Liberal Democrat). There may be strongly partisan voters who would assign all of their votes to one party, but I suspect that most would combine a broad ideological position with support for individual candidates that had impressed them in some way.

Meanwhile, the seven MPs would have an equal incentive to impress all of the county’s voters and to outperform one another whilst also needing strong connections and influence with the full range of local government structures on their patch. Assuming the MPs were not all from the same party, the MPs would also want to highlight their distinct policy and ideological approaches. This would give the voter the choice: perhaps s/he would seek support from a Conservative on a matter relating to local business, a Labour member on the NHS and a UKIP representative on immigration. If the MP you approach first proves inaccessible or unhelpful, there are six others who need your votes and will work for your support. The county boundaries, established over centuries, will not need to change and “frontier communities” are not at risk of being lost between the cracks.

All of this comes at a time of deep disenchantment with British politics, and the boundaries review is a chance to address, not exacerbate this. Could it happen? Almost certainly not. Alas, Britain’s parliamentarians are myopically obsessed with whether one party or another stands to gain or lose from boundary changes, forgetting the far more important question: which system gives voters a sense of connection with their representatives and makes those representatives more likely to work hard in their constituents’ interests.

[1] West Gloucestershire, Tewkesbury, Gloucester, Cheltenham, Stroud, Cotswolds, Dursley Thornbury & Yate (using the proposed 2020 nomenclature)