The politics of a written constitution for Britain

The first issue concerning a written constitution for Britain is: Where is the demand coming from? Contemporary organised demand for constitutional reform traces back to the late 1970s, yet even before then, isolated intellectuals – ‘a voice crying in the wilderness’ – had tried to make an issue out of a written constitution for Britain that would include a Bill of Rights. The term ‘norm entrepreneur’ is sometimes used in politics and international relations to refer to pioneers who, dissatisfied with the status quo, take action to change it at their own initiative. They may make an impression on the world even if their personal cause ultimately fails. A norm entrepreneur is typically an individual, but may be a collective actor …

Let the people speak! The state of devolution, decentralization and deliberation in UK politics

Democratic pressure is building, cracks and fault-lines are emerging and at some point the British political elite will have to let the people speak about where power should lie and how they should be governed. ‘Speak’ in this sense does not relate to the casting of votes — the General Election will not vent the pressure — but to a deeper form of democracy that facilitates both ‘democratic voice’ and ‘democratic listening’.

In the wake of the Scottish referendum on independence the UK is undergoing a rapid period of constitutional reflection and reform. The Smith Commission has set out a raft of new powers for the Scottish Parliament, the Chancellor of the Exchequer has signed a new devolution agreement with Greater Manchester Combined Authority, the Deputy Prime Minister has signed an agreement with Sheffield City Council, and the Cabinet Committee on Devolved Powers has reported on options for change in Westminster. One critical component of this frenetic period of reform has been the absence of any explicit or managed process for civic engagement even though the Prime Minister’s statement on the 19 September 2014 emphasized that ‘It is also important we have wider civic engagement about how to improve governance in our United Kingdom, including how to empower our great cities. And we will say more about this in the coming days’.

The days and months have passed but no plan for civic engagement has been announced.

In the meantime, calls for a citizen-led constitutional convention have been made with ever increasing regularity and volume.

Why the UK needs improved caretaker conventions before the May 2015 general election

In 2010, the UK’s underspecified caretaker conventions caused the “Squatter in Downing Street” controversy, when Gordon Brown remained in office after Labour’s election defeat, pending the completion of the coalition negotiations. Pollsters predict another hung parliament in May this year and potentially protracted coalition negotiations. Yet, the country still lacks adequate rules to govern caretaker situations, which gives rise to considerable risks. Caretaker periods and their attendant challenges are universal to parliamentary democracies. The government’s mandate to exercise its executive powers stems from its ability to command the confidence of parliament. However, there are points in every parliament’s lifecycle when no government can lay claim to such support—between parliamentary dissolution and a general election; after a general election and before …

The future of fiscal squeeze: More of the same?

What can we learn about the future of fiscal squeeze in the UK (defined as substantial political effort to increase revenue or cut public spending or both) from looking at past cases? Is current or recent ‘austerity’ in a class of its own when we put it into historical perspective, or is it part of an evolving pattern?

The table below identifies a total of twenty UK ‘squeeze’ episodes over a century (which can be qualitatively grouped together into roughly thirteen) in which revenue increased or public spending fell by a significant amount relative to GDP. We define a ‘hard squeeze’ as one in which revenue rose or spending fell both in absolute constant-price terms and relative to GDP, and a ‘soft squeeze’ as one in which revenue rose or spending fell on one of those measures but not the other. The table also records the variety of governments involved in squeezing (right or left, coalition, majority-party, minority), the delegation or otherwise of economic policy functions or decision advice relating to interest rate setting, consideration of spending economies, and financial/economic forecasting.

Of course, deriving consistent data series from historical statistics over a hundred years is far from problem-free, so we should not try to read too much into small differences. And two of those thirteen episodes occurred during the special circumstances of the two twentieth-century world wars, involving very sharp revenue squeezes together with cuts in civilian spending to fund a huge blowout in military spending when party electoral competition was largely suspended. But even allowing for such issues, three changes over time stand out from this analysis.

A ‘crowd sourced’ constitutional convention: initiative of the Institute of Welsh Affairs

Why wait for Westminster to grant you a Constitutional Convention?, Guardian columnist Simon Jenkins asked at the IWA’s conference a week before the Scottish referendum. “Hold your own one; decide what you want, and ask for it – you never know, at this time, you might just get it” the former Editor of The Times implored his audience. So that’s what we’re doing. On January 26th we’ll be launching the first ‘Crowd Sourced’ Constitutional Convention on the future of Wales, and the UK. Thanks to dozens of small donations from across Wales, and the support of the UK’s Changing Union project, we are able to launch an eight-week experiment in deliberative democracy to run in parallel with discussions at Westminster …

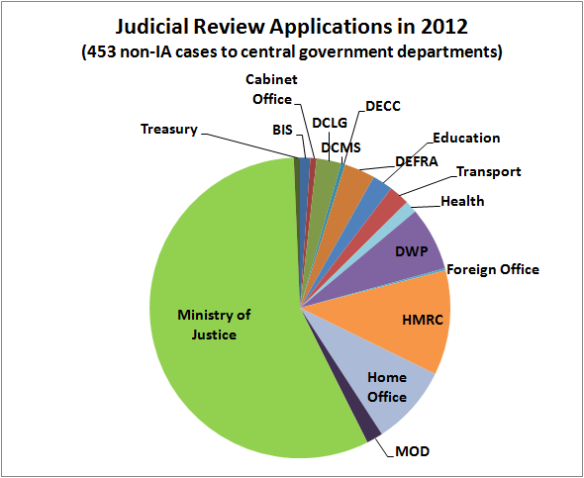

How Many Judicial Review Cases Are Received by UK Government Departments?

During the debate in parliament on Monday 1 Dec 2014, Chris Grayling (Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice) was asked how many Judicial Review cases are brought against government ministers.

Julie Hilling (Bolton West) (Lab): The right hon. Gentleman says “all the time”. Will he give us a notion of how often that is—once a day, once a week, once a month? How many times have such cases happened since April, for instance? He is giving the impression that they happen all the time, but what does that mean?

Chris Grayling: A Minister is confronted by the practical threat of the arrival of a judicial review case virtually every week of the year. It is happening all the time. There are pre-action protocols all the time, and cases are brought regularly. Looking across the majority of a Department’s activities, Ministers face judicial review very regularly indeed. It happens weeks apart rather than months apart.

The minister gave no actual numbers in his answer. So, in this post I’ve looked at how many judicial review (JR) cases were received by central government departments (‘ministers’) over the past few years. This analysis relates to my work with Christopher Hood in the Politics Department at Oxford.

Should a codified UK constitution include reform or attempt to describe current arrangements

In approaching questions of constitutional change I have learned to be circumspect. It is now clear to me – as it was not even a few years ago – that it is entirely possible to find proponents for almost any constitutional position but virtually impossible to locate any argument that has thus far succeeded in triggering principled reform. To say this is not to deny the existence of constitutional change or even reform. The history of New Labour from 1997 continuing through the Brown administration and on into the present Coalition is testament to the shifting of several – some might say rather too many – constitutional tectonic plates. But the shifting of constitutional tectonic plates either randomly or, more …

Citizens should have the power to call constitutional conventions

There is much debate about the need for a constitutional convention for the UK. The case for a convention is strong: the constitutional settlement is currently in flux with cross-party agreement to devolve further powers to Scotland; the Welsh and Northern Irish assemblies want enhanced powers; and there are calls for devolution to the regions and cities within England and/or an English parliament. Older constitutional issues such as the voting system and the future of the House of Lords remain unresolved. A great deal of ink is being spilled on the question of what form any convention should take. A concern that a new settlement will be a stitch-up amongst the major political parties and the vibrancy of the referendum …