Finding the future of democracy in the past

There are two different questions that might be asked about contemporary democracy: how did we get here? And where else might we have tried to get? A great deal of the ‘history of democracy’’ is written in the former mode, with the classical world and subsequent periods being identified as steps in a path towards a modern democratic world in which the people elect their governments and hold them accountable to greater or lesser extents. In Britain, the normal staging posts identified are the Levellers, the 1790s, the Great Reform Act, and the suffragist movement. In America they are the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the Federal Constitution of 1788, Jacksonian Democracy in the 1830s, the Civil War, and the Voting Rights act of 1965. In France, the French Revolution, 1830, 1848, 1871, 1836, and 1944. Ireland has far fewer dates!

This sort of history is in effect being written backwards; it is a history of the present and how we got to it, not a history of the past, and what we might have fought for. One mark of this approach is that relatively little attention is given to the language people actually used; if we think their aspirations were democratic then it is assumed that we can describe their goal as democracy, even if they didn’t use the word. Moreover, since we link democracy to elections, we assume that the history of democratic aspiration was primarily a story of struggle over the suffrage. But much of this does violence to the evidence.

After the Protests: Time for a new politics in Turkey

The balance sheet after three weeks of protests and police violence in Turkey is grim: four people were killed, more than 7,000 wounded, 11 lost their eyesight and several hundred detained. What began as a localised protest over a shopping centre and the demolition of the Gezi Park in Istanbul’s central Taksim Square turned into a nationwide conflagration in response to the inciting rhetoric of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the unfettered police brutality unleashed upon peaceful protestors. The image of German Green Party Chairwoman Claudia Roth, barely able to speak following a teargas attack on her hotel next to the Gezi Park, will come to haunt Turkey’s political elites for years to come.

It is hence not surprising that a significant portion of Turkey’s society, which also feels unrepresented by the infighting-plagued main opposition party, was ready to go to the streets, when the initial protests over the shopping centre were brutally repressed.

Democracy and Foreign Policy Persistence: Why Pakistan’s India strategy under Nawaz Sharif may not see a paradigm shift

Nawaz Sharif, the leader of the Pakistan Muslim League, is back in power. Sworn in as prime minister on June 5th, for the third time since 1990, he has been recognized over the course of his political career as a principal challenger to the military’s supremacy in governing Pakistan. Indeed Mr Sharif’s proactive pursuit of peace with India became the primary reason for his forcible ouster from power by the army in October 1999 and he was subsequently imprisoned and exiled for intruding into what the army considers its exclusive foreign policy domain. But the tide of history has now turned back in his favour and he promises a ‘new chapter’ in the country’s relationship with India. ‘We will start from where we were interrupted in 1999’, he declared as soon as the PML-N won the May 11th elections.

Since his dealings with India precipitated his ouster from power 14 years ago, there is now a heated debate over the prospects of a fast-paced rapprochement with its southern neighbour. Sharif has already pledged to take some bold initiatives: improving trade, energy and transportation links; expediting the Mumbai terror investigations; establishing a commission of enquiry on the Kargil conflict (which had subverted the peace process with India, especially the February 1999 Lahore Declaration); and reigning in non-state actors such as Lashkar-e-Tayba, accused of committing terrorism against India. Indian leadership (from the majority in Congress and the BJP opposition) have wholeheartedly welcomed Mr Sharif’s return to power and his overtures towards India. For now at least, there is visible public optimism in both countries that perhaps the two traditional foes are finally well on their way towards a sustainable course of mutual peace.

The New Bulgarian Government: A fresh beginning or more of the same?

Bulgaria’s parliament recently approved a new centre-left government, ending a three-month stalemate after the previous centre-right government resigned in February 2013 amidst widespread anti-austerity protests. Despite the seriousness of the task it faces, which includes addressing the protesters’ grievances and ensuring Bulgaria’s economic development, due to a lack of parliamentary majority, the new government is unlikely to bring any significant changes and distance itself from the previous one.

The Hypocrisy of the Romanian Government: Why the Rosia Montana project must be stopped.

Whilst in opposition, current Romanian Prime Minister Victor Ponta and his Social Liberal Union (USL), vehemently protested against the Rosia Montana mining project. Now they are in government, something appears to have changed their minds on the matter. The USL should remember that they are only in power as a result of the discontent of the population with the previous government, on issues that included Rosia Montana, and that they can be removed as well, if they fail in their duty to govern according to their mandate.

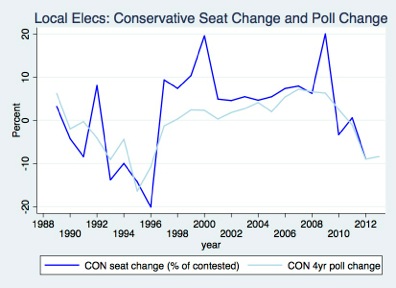

What do the polls tell us about local election results?

While some ask what local election results tell us about the state of the parties and prospects for the next general election, it is also important to consider how national party popularity affects the fortunes of candidates in local government elections. Local elections are often said to be about local issues but actually most of the changes over time in shares of council seats won the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats can be accounted for by changes the popularity of these parties at the national level.

‘Making Thatcher’s Britain’: an interview with Robert Saunders

Robert Saunders is co-editor (together with Ben Jackson) of Making Thatcher’s Britain. He teaches History at Jesus College, Oxford, and Politics at Lincoln College. I really enjoyed Making Thatcher’s Britain. Can I start by asking a biographical question about Thatcher before we get to the book — how did she come to lead her party in 1975? Was it a result of a careful campaign or happenstance? There was a degree of good fortune to the affair. If Ted Heath had resigned a year earlier, or if Keith Joseph had run in 1975, Thatcher would not have been a candidate. She won partly because of a brilliant campaign organisation, and partly because she was the only one willing to challenge such a dominant leader. But …

Kenya’s hopes for justice in the hands of the accused

On March 30, the Kenyan Supreme Court faced its most critical challenge to date, as it delivered its verdict on the petition contesting the results of the presidential election held on 4 March. In its landmark decision the judicial body upheld Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory as declared by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) on 9 March. While the verdict was certainly disappointing for Raila Odinga and his supporters, the decision to contest the election through the Courts and – most crucially of all – accept its verdict, is a powerful vote of confidence in Kenya’s reformed judiciary. Odinga’s decision to contest the election through the Courts stands in sharp contrast to the disputed election of 2007-08. Five years ago, lack of faith in Kenya’s judiciary meant that challenges to the poll results played out in the streets, leading to widespread violence that swept across the country. With nearly 1300 killed and hundreds of thousands displaced, the 2007-08 post-election violence amounted to Kenya’s worst political crisis since independence.