Avoiding Africa’s oil curse

East Africa is the global oil and gas industry’s hottest frontier. Barely a month goes by, it seems, without a major discovery in Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, or the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

This new African windfall is hardly without precedent. Several west and central African states — most notably Angola and Nigeria — have already experienced petroleum booms of their own. Over the last decade, they benefited from a spectacular jump in oil prices, which rose from $22 per barrel in 2003 to $147 per barrel in 2008 and remained high, for the most part, until recently. The spoils were enormous: from 2002 to 2012, Angola’s GDP jumped from $11 billion to $114 billion and Nigeria’s went from $59 billion to $243 billion.

The opportunity afforded by this extraordinary decade was unprecedented and is unlikely to recur. Sadly, however, decision-makers have mostly squandered it. If the new east African producers are not to repeat the mistakes of the established ones, then, they should heed the lessons of Africa’s last oil boom.

The “Aresian Risk” of Unmanned Maritime Systems

We are about to experience a substantial influx of unmanned systems into the maritime military services. On 17 December 2013, the Royal Navy launched a Boeing ScanEagle unmanned aerial system from the Royal Fleet Auxiliary Cardigan Bay, a first for the RN in an operational theatre. This places the Royal Navy alongside the British Army and Royal Air Force in demonstrated drone capability; the latter service has been operating surveillance drones in Afghanistan for years. Since 2012, ScanEagle systems have been in regular use by the Royal Canadian Navy. In May 2013, the Royal Australian Navy announced it would invest up to $3 billion on Northrop Grumman’s new MQ-4C Triton unmanned maritime patrol aircraft. Additionally, the latest Fire Scouts are coming online, Northrop Grumman’s MQ-8C, following its predecessor whose service in the U.S. Navy is now routine. A recent expansion of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., included the opening of a Laboratory for Autonomous Systems Research. The U.S. Navy announced it would introduce mine-hunting surface units by 2017, and it will not be too long before General Dynamics’ Unmanned Undersea Vehicle program produces workable unmanned submarines. Most dramatically, on 10 July 2013, Northrop Grumman’s X-47B fighter drone successfully landed on board the USS George H. W. Bush (CVN-77).

Technological revolutions in warfare, whether bow and arrow, gunpowder, or unmanned systems, inevitably bring about a period of tumult and reshuffling. If we are lucky, such upheaval also brings systematic self-reflection. What changes might this newest revolution in maritime technology bring about?

Women still aren’t the big thinkers in foreign affairs. Why is that?

Lamenting the marginalization of an increasingly cloistered academic elite has once again become de rigueur among the chattering classes. Under the tagline “Smart Minds, Small Impact” Nicholas Kristof recently fired off yet another salvo in the charged debate over the role of the professoriate, lamenting that “my onetime love, political science, is a particular offender and seems to be trying, in terms of practical impact, to commit suicide.” John Maynard Keynes likewise dismissed them as “mad scribblers,” but American scholars of political science and international relations—more so than their counterparts in other countries—are in a comparatively advantageous position to have their ideas fed into the public discourse.

A far more pertinent issue raised by Kristof’s piece is buried in his subsequent blog post: “When I was a kid, the Kennedy Administration had its “brain trust” of Harvard faculty members, and university professors were often vital public intellectuals who served off and on in government.” It bespeaks a nostalgic, if unwitting, yearning for the halcyon days when a coterie of sagacious men brought their talents to bear on considerable foreign policy problems. This “Wise Men” syndrome perpetuates outdated notions of what it means to be a “great thinker” in this field. The real problem with political science academe today isn’t that the professoriate’s leading lights and prominent graduates are incapable of disseminating impactful ideas. The pages of Foreign Affairs are littered with pontifications by top-notch scholars such as Robert Jervis, John Ruggie, and Vali Nasr, who moonlight as governmental consultants, as well as by respected academics such as Stephen Krasner, Francis Fukuyama, and Joseph Nye, who have all experienced stints in public service. The problem, rather, is that still so few of them are women.

Rare-earth metals: anticipating the new battle for resources

Natural resources are pivotal in international politics. They create patterns of cooperation, dependencies and alter balances of power. The battle for resource is most commonly associated with energy resources such as oil and gas, or base metals indispensible for industries: aluminium, copper, lead, nickel and zinc.

In recent years, China has gained the reputation of a resource-avid country, pursuing deals for resource exploitation to its advantage. In numerous countries across Latin America, Asia or Africa, China has already established long-term deals with governments to obtain access to vital metals or resources.

In light of such narratives and records, a lesser-known fact about the geopolitics of resources has escaped public polemics. This refers to rare earth metals or rare-earth elements (REMs), a set of 17 naturally occurring non-toxic materials, which play a pivotal role for emerging technologies and which are predominantly produced and exported from China.Estimations of China`s hold on the REMs market are as high as 97% of the world production.

Gaza is Israel’s Munich

In September 1938, European statesmen gathered in Munich for a fateful conference. Hitler wanted to annex the Sudetenland, a German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia; Britain and France, desperate to avoid war with Nazi Germany, caved in and granted the Führer’s request. It was hoped that Hitler’s appetite for territorial expansion would be sated: Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s prime minister, proclaimed that the concession had achieved “peace for our time“. Within a year, Hitler had invaded Poland and the Second World War had begun. The policy of appeasement, it appeared, had failed and forever would fail – or so it came to be thought.

As the twentieth century evolved, ‘appeasement’ evolved into a term of abuse that would automatically discredit the granting of concessions to satisfy an opponent. What had previously referred to the pacific settlement of disputes through pragmatic negotiation, argues historian David Dilks, “came to indicate something sinister, the granting from fear or cowardice of unwarranted concessions in order to buy temporary peace at someone else’s expense”. The spectre of Munich came to hang over every international crisis: the Korea, Vietnam, Falklands and Suez wars were all justified in terms of the inevitable failure of appeasement. Most recently, the willingness of the West to allow Crimea to fall to Russia has been denounced as ‘appeasement’, and it is common to hear the crisis spoken of as ‘Obama’s Munich‘.

The 2005 Gaza Disengagement was Israel’s Munich moment: in Israeli discourse, ‘Gaza’ is to ‘unilateral withdrawal’ what ‘Munich’ is to ‘appeasement’. Israel withdrew its army and 8,000 settlers from Gaza Strip; the power vacuum was soon filled by Hamas, and this densely populated coastal strip became a launching pad for thousands of rockets against Israeli civilian areas, provoking two mini-wars.

Building a federal Ukraine?

The idea of a remaking of Ukraine’s constitutional order along federal lines is beginning to gain traction. On March 18, Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk reached out to Russophones in the eastern and southern regions, announcing that “new measures linked to decentralization of power will be reflected in a new constitution.” Senior U.S. administration officials have encouraged the Ukrainian leadership to consider constitutional reform along federal lines.

On March 17, the Russian Foreign Ministry proposed the establishment of an international “support group” to manage the crisis. The list of items that Russia wants to be the basis for negotiation in Ukraine includes a new federal structure for Ukraine and the recognition of Russian as a second language.

Until recently the federal idea was an anathema among the greater part of Ukraine’s political elite. As a constitutional form it was largely rejected in the 1990s, partly as a negative reaction to the experience of Soviet federalism, and partly from fear of its centrifugal potential for splitting the country along ethnolinguistic fault lines.

Cloaks of Invisibility: The latest frontier in military technology

Fiction and reality have meshed to incredible extents in the past decades, and it is no longer a surprise to see sci-fi-inspired inventions used in everyday life. The military field has been no exception and is now at the cusp of groundbreaking innovations that could change war-making to its core.

The next frontier in defense technology is so-called “stealth” technologies, in which the U.S. military has already invested huge funds. New research is opening up the prospect of achieving something close to invisibility on the battlefield, a breakthrough likened to Harry Potter`s famous invisibility cloak. While most stealth technologies are designated to elude enemy radars, new invisibility technologies could conceal objects in real time, not just from radar but from the naked eye.

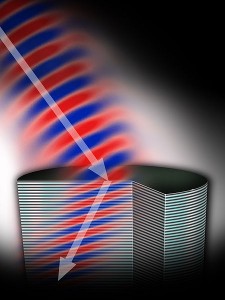

The science of invisibility took off in the mid 2000s. This research has mostly involved the use of metamaterials, which are extremely thin composites that bend electromagnetic waves in a way that negatively refracts lights. Cloaking mechanisms use metamaterials to route light waves around an object and create the sensation of looking through the object.

Crimean autonomy: A viable alternative to war?

The issue of Crimean separatism is not new. In the early post-Soviet period it became one of the biggest challenges newly independent Ukraine had to manage. A closer look at the events of the early 1990s and the concept of Crimean autonomy helps to put current events in perspective and points to an alternative to war. A history of fractious multi-ethnicity, a legacy of autonomy experiments, a Soviet-era transfer from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954, a center-periphery struggle in Ukraine, economic dependence, the tense relationship between Ukraine and Russia, and readily available military resources (in the form of the Black Sea Fleet) account for the complexity of the ‘Crimea question.’ Separatism peaked in 1992-1994, and internal and …