The Democracy Commission: practically teaching democracy

The institutions, technologies and practices of British democracy are, for the most part, inventions from before the time of universal suffrage. In the fluidity and fracture of the 21st century, it is clear this democratic inheritance has become increasingly inadequate. Sharp, sustained differences in participation and voice by age, class, ethnicity and region have become entrenched. Politics has professionalised, class identities have weakened, and political parties have drifted from their anchors in civil society, left ‘ruling the void’. Reinforcing the post-democratic drift, the evolution of the UK’s political economy has shrunk the potential scope for and influence of collective political action and democratic participation. The general election clarified our evolution towards a divided democracy. As IPPR’s new report into political inequality shows, less …

Six reasons why the UK parliament should have youth quotas

Young people are disadvantaged economically yet politically marginalised and demonised. Are youth quotas in parliament part of the answer? It is now widely acknowledged that young generations are faring particularly badly in Britain.[i] There is growing concern for a ‘jilted generation’ burdened with debts and structural unemployment. In 1992, the unemployment rate of the young was twice as high as for the rest of the population; two decades later, it is up to four times higher.[ii] Even when they do have jobs, young people are disproportionately likely to be in precarious positions such as zero-hour contracts, temporary contracts and unpaid internships. Despite this context of job scarcity and the structural precariousness they have to face, the young are often regarded …

Predisposed Tabula Rasa

Studies of human behavior and psychology have received extensive attention in public policy. Economists, social theorists and philosophers have long analyzed the incentives of human actions, decision making, rationality, motivation, and other cognitive processes. More recently, the study of happiness furthered the debate in public policy, as many governments brought up the necessity for new measures of social progress. The discussion was bolstered when the UN passed a critical resolution in July 2011 inviting member countries to measure the happiness of their people as a tool to help guide public policies. It was also hoped that discussions about happiness would serve to refine the wider debate about the UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2015-2030 and the standards for measuring and understanding well-being. The World Happiness Report, a recent initiative, attempts to analyze and rate happiness as an indicator to track social progress.

These recent initiatives serve as reminders that sound public policies must evolve in strong connection with an understanding of human psychology, emotions and the sources of happiness and satisfaction. Nevertheless, there are further invaluable insights from neuroscience that have remained less explored. Contemporary neuroscientific research and an understanding of the predispositions of our neurochemistry challenge classical thought on human nature and inform us of fundamental elements that must accompany good governance.

Between Nation-State and Ummah’s Appeal: The contradictions of Islamism in contemporary India and Bangladesh

Generally, Islamists believe in the Universalist concept of Ummah (Islamic community of believers), a supranational or transnational union. The Islamists’ call for unity of the Ummah is based on the belief that Muslims throughout the world should have a sense of solidarity among them cutting across the borders of the nation-state. In this respect, Islamism has justifications to oppose the concept of the nation-state. The Islamist ideologue Maududi (1993) was opposed to the idea of the nation-state, and citizenship based on nationality, considering nationalism to be divisive and as such incompatible with Islam (Maududi 1992).

Conceptually, ‘Ummah’ incorporates the Muslim community in the world as a whole. Therefore, Islamism always tries to claim itself as a ‘mass ideology’ instead of a ‘class one’. For a mass ideology, it asserts the unity of ‘Ummah’ where persons across class, national, linguistic and gender divides can become a part. As an effective tool of political mobilization, the universal concept of Ummah is absolutely crucial in Islamist political ideology. In Laclau’s (1996) terms, one can argue that in Islamist politics, Ummah acts as an ‘empty signifier’ around which different particularities are organized to claim a common universal identity. The idea of Ummah provides the ground for Islamists to take the challenge of rallying the entire Muslim community under a single political project, a project I call Islamist populism.

Digital rights and freedoms: Part 2

More than rights, a set of guiding principles is needed to counterpose to the reigning ideals of ‘security’, ‘growth’ and ‘innovation’. Alternative ideals, perhaps, such as democracy, health and environmental sustainability? See part one. The net has the potential to revolutionize democracy with an informed citizenry empowered to deliberate and decide on key issues. Yet current trends strengthen anti-democratic forces. In addition to concerns over privacy, there is an urgent need to address how the public realm is being hollowed out by corporate interests and advertisers. The ideal of democracy presupposes a shared public sphere in which citizens can construct, debate and decide on collective projects. This requires access to quality information and while the net has certainly increased the …

Digital rights and freedoms: Part 1

Under the rubric of state security on the one hand and commercial openness on the other, we are being lulled into an online world of fear and control where our every move is monitored in order to more efficiently manage us. This article launches a new section of the Great Charter Convention dedicated to debate and analysis of democracy, politics and freedom in the digital age. It is clear that we are at a crucial historical juncture. The issues around state power and surveillance raised by Edward Snowden’s revelations should be an important theme in the upcoming general election, while the symbolic double anniversary of Magna Carta (aged 800) and the web (aged 25) offers an opportunity for critical reflection on how …

Is federalism a viable option in Spain?

The Spanish state has been suffering from a deep crisis for several years, as Basque and Catalan claims for the ‘right to decide’ have clearly illustrated. Thus, it’s hardly surprising that the federalist option has been rediscovered as a way to solve the problems of the ‘State of Autonomies’. Is federalism a realistic solution?

To answer this question, two aspects should be considered: 1) the potential of federalism as a solution to the specific problems linked to national pluralism; and 2) the viability of federal reform in Spain.

1. Federalism and national pluralism

Federal studies have been considerably revived over the last 20 years and have abandoned some of their former beliefs or convictions. Federalism is not a panacea for solving problems of national pluralism in democratic contexts. Nor is federalism is a project necessarily concerned with national diversity (see Seymour and Laforest 2001: 9-10). This renewal has been greatly motivated by the difficulties encountered in advanced democratic systems (Canada, Belgium, Spain, to give a few examples) to reconcile deep diversity with the specific demands of the democratic principle. That is what Carl Schmitt already referred to in 1928 (2003: 356) when he emphasized the necessity of (existential) cultural and political homogeneity to ensure the stability of federal states. Empirical evidence confirms the German jurist’s theory. The great majority of federations, including those which started with important cultural and political diversity, evolved towards a form of Unitarian federalism which, in its fundamental aspects, eventually adopted the shape of the dominant State, the Nation-State (one State, one people). Schmitt refers to this federal form as ‘the federal State without federal bases’ (2003: 368). In the most recent specialized literature calls this type of federalism ‘territorial federalism’, that is to say a way to organize the political power of a single people or nation from a legal and territorial point of view (otherwise known as a monistic theory of federalism; see Karmis and Norman 2005: 3-17).

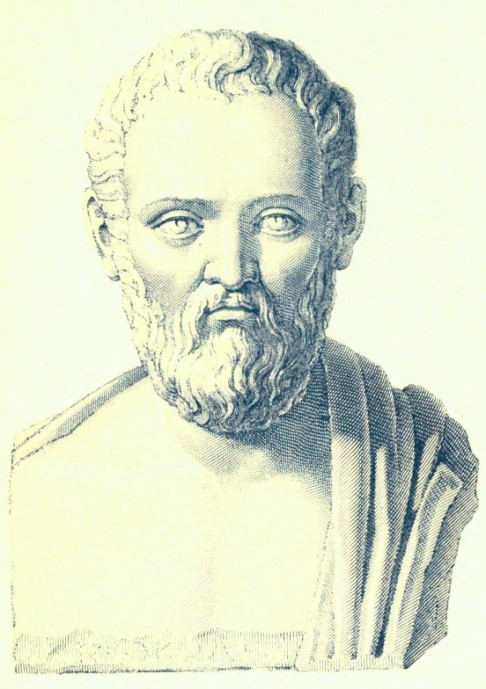

Nurture and nature: education, blood and nationality

On the 28th of October 1940 the Greek government rejected Benito Mussolini’s ultimatum demanding that Axis forces were given free entrance from neighbouring Albania and allowed to occupy strategic locations around the country. After the war, this momentous event in the history of modern Greece – popularly known as the No Day – became a national holiday, celebrated annually with impressive military and student parades.

Fourteen years ago, one such parade had to take place in a town near Thessaloniki. As a tradition, the best student in the local high school was expected to bear the Greek flag. The best student, though, was not Greek. He was an Albanian immigrant.

Pupils, parents and citizens throughout Greece rose in anger: despite his achievement, how could a non-Greek, an alien, a non-citizen at that, be allowed to carry the national colours? The government, the main political parties and the teachers’ union stood behind the excellent Albanian student but the boy responded to the growing commotion by choosing to step aside, allowing a Greek pupil to carry the flag.

Three years later, the same Albanian – having now distinguished himself as the best graduating student of his school – was again elected to bear the colours in the Greek national holiday parade. The public outcry, in this instance, grew even wider and sharper than earlier. The young man, for a second time, decided not to accept the honour but pass it on to a native schoolmate instead.

The volcanic public discourse surrounding these events had nationality, citizenship and ethnic origin at its centre. Blood, heredity, and even DNA, became salient elements of the debate – pitted against the qualities and achievements of the person, his or her social integration, active participation in and contribution to the Greek scheme of life. ‘What makes one truly Greek: one’s Hellenic outlook, behaviour and genuine belief in Greekness, one’s abilities and success in Greek society and/or one’s historical roots and genetic ancestry?’ was a question resounding loudly across the country and the region. Is it nature or nurture, a cocktail of the two, or perhaps something greater than that, which makes us genuine sons and daughters of a country, a nation or a people?

The perennial echo of this problem was picked up by the then president of the Greek Republic who, in defence of the Albanian student, quoted a line from a famous work by the great Athenian rhetorician Isocrates. “[Athens]”, the ancient man of letters writes in his Panegyricus, “has brought it about that the name Hellenes suggests no longer a race but an intelligence, and that the title Hellenes is applied rather to those who share our culture than to those who share a common blood”.