Index on Censorship student blogging competition

Index on Censorship is seeking entries for its student blogging competition. To enter, students should submit a 500-word blog post on the following topic: ‘What is one of the biggest challenges facing freedom of expression in the world today?’ This could cover a repressive regime, threats to digital freedom, religious clampdowns or attacks on media freedom, focusing on any region or country around the world. The competition is open to all first-year undergraduate students in the UK, and the winning entry will be determined by a panel of judges including the Index Chair. The winning entry will be published in the Index on Censorship magazine. This is a opportunity for talented student writers and activists to get professionally published and make contact …

Relativism and Political Justice: an ancient problem comes to the modern age

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus tells a famous story of the Persian king Darius who one day decided to summon a group of Greeks to his court to ask them a very strange question; for what price would they eat the bodies of their dead parents? The Greeks respond with horror, and say there is no price on earth that would lead them to do such a thing. Darius then summons members of a tribe known as the Callatiae who DID eat the bodies of their kin and asks them for what price they would cremate their dead – the practice of the Greeks.

The emergence of ‘realism’ in political theory has the potential to change how we think about the real world of politics

Political theorists talk about justice and equality, liberty and democracy, revolution, alienation, liberation, and a lot more besides. Their expertise lies in being able to disagree with each other in great detail on a series of topics that are fundamental to politics and society world-wide. Although the terms political philosophy and political theory are used rather indiscriminately, those who think of themselves as political philosophers tend to link what they do closely to philosophical and moral principles; while those who call themselves political theorists tend to appeal to facts about the world and to the way in which the structures and processes of social and political life limit the possibilities for the realisation of those principles by political agency.

Anarchists and Republicans: Bedfellows?

In 1797 two of the foremost radical social critics of their day Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin married in order to legitimate their unborn child. Both opposed the institution of marriage but they hoped to avoid the scandal and prejudice that had accompanied Wollstonecraft’s first illegitimate child. Their brief relationship was one of the happiest periods in their often tumultuous lives but was tragically cut short by Wollstonecraft’s death in childbirth.[i] Wollstonecraft’s powerful feminist critique of the patriarchal beliefs and institutions of her day drew on many republican themes, extending the traditional republican concern with political domination to the social domination of husbands over wives.[ii] Godwin’s philosophical rejection of external authority and his exposition of a decentralized voluntary society free from the state has led many to classify him as an early anarchist thinker.[iii] If their marriage could be considered the highpoint of relations between republicanism and anarchism, the two traditions have since followed very different ideological and political paths. In what follows I consider what, if any, potential overlap there is today between these two often neglected political theories.

How the advent of autonomous drones will affect our conception of ethics

Georgia Tech professor Ronald Arkin contends that we might soon see the advent of autonomous drones operated by algorithmic ‘ethical governors’ replacing human decision in warfare. As Peter W. Singer’s argues in his seminal book Wired for War, this prospect does not belong to the realm of science fiction: we are amidst a revolution in military warfare, with digital and robotic technology increasingly replacing human decision in contemporary warfare.

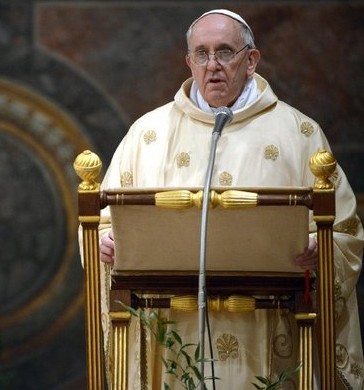

The utility function of Celestine V and the election of Pope Francis

When Pope Benedict XVI resigned in February 2013, there was much scrabbling by journalists to establish when last a pope resigned voluntarily. After a bit, they came up with the correct answer. It was in 1294, when the elderly hermit Pietro of Murrone, who had been elected as Celestine V after a two-year deadlock, abruptly resigned after five months and went back to being a hermit, a life he evidently preferred. But Celestine V was remarkable for two things, of which his resignation was but one. The other was his enforcement of the conclave. That distant event has decisively shaped the procedure for electing popes. To see why, we need to understand a lesson from social choice that papal electors learnt the hard way: the trade-off between stability and decisiveness.

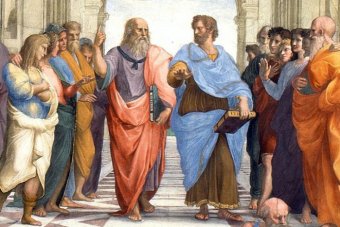

Remembering what the Greeks taught us

Re-reading Plato and Aristotle has made me to realise that by neglecting ancient philosophies and being preoccupied with neo-liberal thinking stemming from utilitarian philosophies have led us to a major crisis in our political and governmental affairs. The vital institutions of our democracy are now widely held in contempt by the public because we have neglected the foundations that underlay their former respect. Having forgotten the teaching of Plato, Aristotle and many other thinkers and subscribed to only judging actions by their consequences, the result is a major crisis of confidence in our political and government systems. What have we lost?

Unpacking ‘the 99 per cent’

Occupy has spotlighted the super-elite, but the ‘average Brit’ that is pitted against this class does not exist. For the struggle to empower all citizens to succeed in Britain, mapping actual wealth distribution is critical. [This is the second of three pieces exploring wealth distribution in Britain. It sits within our Democratic Wealth debate, in partnership with OurKingdom.]