Netanyahu and the two-state solution

Israel’s international image has suffered tremendously in the past few years. Repeated wars in the Gaza Strip, the continued construction of housing units in Jerusalem and the West Bank, and Benjamin Netanyahu’s provocative rhetoric during his most recent bid to win re-election have poisoned the relationship between Israel and the international community. 2014 proved to be the year of Palestinian statehood recognition votes in Europe. Parliaments from Portugal to Ireland, all the way to the European Parliament in Brussels have considered recognition. Though cautiously worded, the motions indicate a change in the international mood surrounding the Middle East conflict. Netanyahu’s most recent declarations of support for the two-state solution reflect the deep concern that has spread in Israel regarding what is for the first time serious international pressure on the country. But does this necessarily translate into a bright future for the Peace Process?

Netanyahu’s interest in a two-state as opposed to a one-state solution should not take us by surprise. The latter would mean an Arab majority in the would-be Jewish state. At this time, about six million Jews and six million Arabs inhabit the territories of Israel and the future Palestinian state. With a higher Arab fertility rate, Jews would soon be a minority in such a state. Moreover, Palestinians seek the right of return of their over five million refugees as part of the state-creating deal, and it is to be expected that the state would attract a greater number of Palestinian refugees than of Jews eligible to return to Israel. It follows that a one-state solution spells the unthinkable for Israel.

The perils of Turkish presidentialism

With Recep Tayyip Erdoğan sworn in as Turkey’s first popularly elected president last August, the debates on adopting a presidential system have once again come to the forefront in the run-up to the Turkish general election in June. The most important implication of the election will be whether it will lead to a formal move toward presidentialism in Turkey’s constitution.

Prior to the election, Turkey’s political system was admittedly complex. In 2007, Abdullah Gül, Erdoğan’s predecessor, was the last to be elected under the former system, in which parliament elected the president. He took office following a strained process between the Justice and Development Party (AKP), the Turkish Armed Forces, and the Republican People’s Party (CHP). The first presidential election in April was boycotted by the CHP. The Chief of the General Staff of the army made statements expressing the wish for a sincerely secular president, and published an e-memorandum warning against emerging disputes regarding the secular nature of the Turkish republic in the context of the election. Eventually, the AKP called an early general election in July, after which the presidential election was re-held in August.

As a further response to the crisis, the AKP held a referendum in October, ensuring the popular election of the president. Thus, Turkey remained a parliamentary system with a ceremonial president until the first popular presidential election was held, and Erdoğan was elected last year. Now, the system has become semi-presidential with both a popularly elected president and a prime minister responsible to the legislature. Crucially, the president does not hold substantial executive powers.

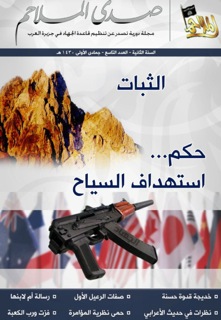

Oxford’s Elisabeth Kendall on Jihadism and the use of poetry

What is it that turns peace-loving Muslims into militant Islamists? There are many answers to this complex question. One angle that might not naturally spring to mind is poetry. Yet this is what Dr Elisabeth Kendall argues in an interview for BBC Radio 4’s “The World This Weekend” with Mark Mardell.

Questioning traditional citizenship: memory, identity and collective action in Chile

In this post I contest traditional liberal conceptions of citizenship rooted in the nation-state and consider the role played by memory in the ways in which Santiago de Chile’s disenfranchised produce contentious politics.

I suggest that, by referring to the past in their meetings and conversations, local neighbourhood organisations in Santiago de Chile’s poor settlements (poblaciones) assert a particular, anti-hegemonic interpretation of history. Through stories, historical anecdotes, and different types of memorials, poor residents produce a neighbourhood identity, giving rise to innovative forms of community membership.

Referring to the influence of the past in contentious politics in the favelas, James Holston has also proposed novel approaches that allow a rescaling of citizenship. In his book Insurgent Citizenship, Holston (2008) argues that history lurks below the surface of our porous present, sometimes leading to the eruption of movements that question historically entrenched regimes of urban citizenship. However, Holston does not explain precisely how this determining relationship between history and contentious mobilisation occurs. My ethnographic research in Santiago’s poblaciones explores this issue directly, examining the role of memory in the production and re-production of an identity of struggle.

The rise of populism in Southern Africa’s dominant party states

Over the past two decades the countries in southern Africa have generally had ‘dominant party systems’. Such party systems consist of one large ruling party which is dominant, in terms of seats in the national assembly or incumbent advantages, and a number of small opposition parties. The literature on dominant parties (Bogaards, 2004 and Greene, 2007) and competitive authoritarianism (Schedler, 2009 and Levitski and Way, 2010) provide useful insights for understanding the party politics of the region. The dominant party is usually a former liberation movement which fought to end colonialism or white minority rule. Nicholas van de Walle observes that opposition parties in the region lack the financial and organisational ability to compete with the incumbent advantages of ruling parties. As such, they remain small and fragmented. The dominant parties in southern Africa maintain their hold on power through a mix of co-option and coercion and are not unlike their counterparts in other competitive authoritarian states such as Mexico, Argentina and Russia. For example, mass political rallies are held to demonstrate the ruling party’s extensive support base. People are allegedly enticed to rallies with gifts in cash or kind. In addition state media are manipulated to give the ruling party more coverage and draw attention to its achievements and the government attempts to control the media through regulation or intimidation.

‘We are Sierra Leoneans, not slaves’: contesting citizenship in Freetown

In the summer of 2013, Freetown’s King Jimmy Bridge collapsed. This was around a decade after the end of Sierra Leone’s civil war, and a year before the outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus; needless to say, the resulting deaths seemed barely newsworthy.

But King Jimmy Bridge, and the tunnels that it took down with it, had particular significance to the many young people who make a precarious living in the neighbouring streets’ vibrant informal economy. The tunnels bore the marks of the chains used to imprison the victims of the Atlantic slave trade, as passages to the Ocean they were about to cross. Before King Jimmy Bridge collapsed, the tunnels served as congregation spots for young people, where discussions ensued about their current predicaments and about the plight of the youthman in a country where high rates of youth unemployment have forced a generation into marginal and irregular income-generating activities.

The powerful symbolism of Sierra Leone’s historical memory of the slave trade (see Shaw 2002) was not simply embodied in marginal youths’ existence in the tunnels under King Jimmy Bridge. It was also explicitly evoked in their articulations of a political imagination based on notions of a citizens’ right to work. In the aftermath of an urban beautification project, Operation WID (Waste management, Improvement of the roads, and Decongestion), that curtailed street trading and commercial motorbike riding, young people’s frustration at this blow to their livelihoods was expressed through a poignant refrain: “We are Sierra Leoneans, not slaves!”

The push and pull of the world’s most dangerous migration route – what’s really behind the flock of thousands to Europe these days?

The Mediterranean Sea is today’s most dangerous border between countries not at war with each other. Just last week, 300 persons departing Libya on four rubber dinghies have gone missing at sea, after drifting for days without food and water. News reports in the past six months have regularly commented upon the rising number of persons disembarking on Italy’s coastline – benefiting from its search and rescue operation Mare Nostrum. Despite the increase in new arrivals from 33,000 to 200,000, the life-saving mission has now been discarded. Italian policy makers believe Mare Nostrum is as responsible for overcrowded reception centres as it is for the rising number of persons risking their lives at sea. But is it truly to blame for the surge? Because more than 50 per cent of arrivals are either Syrian or Eritrean, news commentators have provided some other potential explanations. Some point to the protracted conflict in the Middle East, whilst others highlight the strain on neighbouring Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq in continuing to receive thousands of Syrian refugees. “Poverty in Africa” is mentioned occasionally, and for the better informed, an oppressive military regime and indefinite conscription in Eritrea are to blame. Yet these supposed ‘causes’ of the latest wave in irregular migration to Europe are speculative at most and have in fact been ongoing for many years now.

The irregular and mixed movement of persons across borders is arguably the most pressing international issue of our time, second perhaps only to terrorism. Yet the response of nations is too often reactionary and punitive towards individuals making the move, causing policies like Mare Nostrum to be cut short. By pinpointing the multiple ‘Push’ and ‘Pull’ factors at play in the regions concerned it is possible to generate fresh insight on the debate on South- North migration.

‘Push Factors’

For Syrians and Eritreans on the move, the situation at home is the key reason for flight. In Syria, there are immediate threats to life, regardless of which side of the conflict you are on. In Eritrea, an oppressive military regime and a lifeless economy force several thousand to walk across its land borders every month. Ruthless and indiscriminate conscription waves can also augment departures, as can changes in border surveillance, including the reported end to the notorious ‘shoot to kill’ policy.

Plurinational citizenship in the making

In 2009, after a long and contentious process of national dialogue that led to the approval of a new Constitution, the Republic of Bolivia officially changed its name to Plurinational State of Bolivia.

Over the last decade, the idea of plurinationalism has influenced public debates across the Andean region. In 2008, the Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa defined plurinationalism as the coexistence of several different nationalities within a larger state where different peoples, cultures and worldviews exist and are recognized. Yet, Bolivia was the first country to go all the way, not only including this idea in the Constitution (as Ecuador did) but actually changing its official name. This is not just a formality. The new Bolivia is engaging in a process of in-depth institutional reforms, challenging mainstream narratives and political structures and reinventing a model of the state and creating notions of citizenship better suited to highly diverse ethnic and cultural landscapes.

In Latin America, the effort to challenge assimilationist and universalist models of citizenship (both republican and corporatist) took shape during the 1990s, when multicultural politics emerged and culture and identity became legitimate political claims. However, multiculturalism was not an easy partner for the neoliberal consensus, and claims for collective (rather than individual) rights and for territorial autonomy raise what Deborah Yashar (1999) calls a “postliberal challenge”. While concepts such as multiculturalism and pluricultural citizenship were a key part of the neoliberal agenda, it was with the Leftist turn in the following decade that the more radical idea of a plurinational state took shape. In Bolivia, the election of Evo Morales as President in 2005 and the rise of the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) gave political meaning to plurinationalism as an alternative model of state and citizenship, which was meant to overcome the neoliberal multicultural framework for diversity management.