How Europe exited its crises: is there a federal future for Europe?

Over the past four years some of us may have forgotten that the financial crisis did not start in Europe, but in the USA. If it makes sense to ask ourselves where it all started, it is even more relevant for us to understand what happened on this side of the Atlantic. It is in fact in Europe that the crisis (or the crises) has found a fertile ground to develop and unravel the Eurozone. “Spread”, “bailout”, “rating agency” have become terms that Europeans have become acquainted with, while austerity policies have hit them as it has not happen for decades.

In addition, the crisis came at a time of extreme volatility in global, European and national politics and has arguably contributed to accelerate some trends which were already starting to appear at the beginning of the century. The consolidation of Asia as the new engine of economic growth; the rise of new economic powers such as the BRICS; the negotiations of extensive Free Trade Agreements in an attempt to benefit from access to growing markets and to US to maintain an upper hand in setting global standards (among the others the EU and South Korea FTA and the on-going negotiations between EU and Canada, and the EU and the USA). Domestically the EU is also facing new tensions: a sharp rise of euro-scepticism and of nationalist movements has been registered in many European countries, including Italy, France, Germany, Hungary and the UK, with the UK arguing for a referendum on its own EU membership in 2017. Separatist movements are getting stronger in several regions including Scotland, Catalonia and Flanders. Last but not least, socio-economic challenges are increasingly evident, with unprecedented rates of youth unemployment, an ageing population and the European welfare systems increasingly under pressure.

Together these external and domestic challenges, mixed with the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis in all its facets, constitute an explosive mix. As we are approaching a key electoral year, with the elections of the European Parliament as well as with national elections in several countries including Germany, it is about time to draw some lessons from what happened in Europe and to envisage a possible way to move forward.

The case for political reform in Europe

The recent economic crisis has revealed, amongst other things, that certain political systems in southern Europe seriously struggle to deliver good governance. Political elites in Italy, Greece, Portugal and Spain have not only proven incapable of delivering prosperity to their people but have presided over (and in some cases profited from) highly corrupt structures. Although austerity and economic recovery have been given priority until now, it is high time political reform is discussed, and the root causes of this crisis are tackled. The inability to do so would have consequences that go well beyond the borders of Europe.

The shortcomings of political systems in the south of Europe have manifested themselves in two fundamental ways. The first has been through the failure of elected leaders to bring prosperity to their people. With years of economic recession, several bailouts and a generation of young people forced to leave their countries in search for jobs, it is hard not to question the ability of past Spanish, Greek, Italian and Portuguese governments. In Italy and Greece the incapacity of elected leaders to tackle the economic crisis was so great that government responsibilities had to be handed over to “technocrats”. These highly qualified caretakers were asked to accomplish in a very short period of time what traditional political leaders had failed to do in decades: keep public spending under control, and make their countries’ economies more competitive.

Sweden’s Social Democrats: the insider-outsider dilemma

The most important event in Swedish party politics in the past twenty years is the decline in the electoral fortunes of the Social Democratic Party.

For most of the post-war period, electoral support for the Social Democrats hovered around 45 percent. As late as 1994, in fact, the Social Democrats won 45.3 percent of the vote. Their best election since then was in 2002 (39.9 percent). In 1998, they received 36.4 percent; in 2006, 35.0; in 2010, only 30.7.

What sets the elections of 2006 and 2010 apart is that the combined support for the center-left fell sharply. The Social Democratic losses in 1998 were associated with a surge in support for the Left Party, allowing Göran Persson to remain as prime minister after the election. Between 2002 and 2010, by contrast, the support for the Left Party and the Greens did not increase at all; the combined support for the center-left therefore fell from 53.0 to 43.6 percent.

These are momentous changes, and scholars and political commentators will no doubt puzzle over them for years to come. In a recently published paper, we show that an important part of the explanation is that the Social Democrats have become unable to reconcile the demands of two groups of voters that have traditionally sup-ported them: on the one hand labour market “outsiders,” who have insecure jobs or no jobs at all; on the other hand labour market “insiders” with stable employment. The deep economic crisis in the 1990s changed the Swedish labour market. It greatly increased the number of outsiders, rendering the latent conflict between insiders and outsiders salient.

The push for a transatlantic trade deal: should ‘culture’ be off the table?

When in February 2013, US President Obama called for negotiations on a US-EU free trade agreement and was immediately echoed by EU officials van Rompuy and Barroso, widespread enthusiasm came first: Businessmen cheered the vision of joining the two regions accounting for almost half of the world’s GDP, and economists stood ready to present their age-old calculations about the benefits of free trade. Yet soon, controversy rose, and some Europeans had their reservations about deregulating their cultural industries. Does free trade work for European culture?

In times of crisis, the (all but new) idea of free trade in the North Atlantic area comes in handy. Certainly, agreement over the “Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership” (TTIP) could remove unnecessary trade barriers and boost growth at no cost. In the words of EU trade commissioner Karel de Gucht, it is “the cheapest stimulus package you can imagine”. If negotiations succeed, Europeans can expect the creation of some 400,000 jobs, according to the Commission’s calculations. Given the state of labour markets, a spark of hope.

When the Party’s Over: The Politics of Fiscal Squeeze in Perspective

Fiscal austerity, fiscal consolidation and spending cutbacks currently dominate the politics of many of the world’s democracies. Old political arguments are being tested with new battles emerging over whose expectations are to be disappointed and who should be blamed for fiscal squeeze. Can the fiscal travails of the early United States in the 1840s, when half of the states then in the Union had to default over their debts and new unpopular taxes had to be imposed in the middle of an international trade slump, help us draw lessons for the Eurozone debt crisis of the early 2010s? Could cases often presented as ‘poster children’ of successful fiscal consolidation (and at those often portrayed as failures or ‘basket cases’) inform us about the politics of those fiscal squeezes? Can governments that copy ‘good’ examples of fiscal squeeze escape punishment at the polls? A recent conference on the politics of fiscal squeeze explored some these issues and looked at how it has played out in different times and places. It considered in depth nine cases of fiscal squeeze (defined as the political effort that goes into reining in expenditure or raising taxes) and explored what conclusions we can draw for current debates about fiscal squeeze from earlier cases in other democracies.

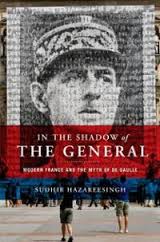

De Gaulle’s lasting influence: A Q&A with Dr Sudhir Hazareesingh

Sudhir Hazareesingh talks to Gavin Jacobson about his recent book, In the Shadow of the General: Modern France and the Myth of de Gaulle (New York, Oxford University Press, 2012).

Gavin Jacobson (GJ): Perhaps you could begin by telling us about what led you to start thinking more closely about Charles de Gaulle, and why you decided to write this book.

Sudhir Hazareesingh (SH): When I was finishing my book on the Napoleonic legend, I concluded that since the 1980s, General de Gaulle had become France’s favourite national hero. I found this intriguing, especially as de Gaulle seemed to have been adopted by the Left, who had opposed him vigorously for much of his time as president. So I thought it would be interesting to explore how and why this situation had come about – and also how this Gaullist cult compared with its Napoleonic predecessor. So this is what the book eventually became: a study of what de Gaulle has come to mean to the French, and what his iconic status tells us about French political culture.

GJ: Could you give us some idea of what you mean by ‘myth’? How is your understanding of it here different from the way people like George Sorel have previously defined it, for instance?

SH: I use ‘myth’ to denote an idealized representation of a phenomenon, either by a collectivity as a whole, or within a specific ideological framework – it can refer to a historical moment, like the French Revolution; certain moral and political values (‘we are a freedom-loving people’); exemplary social groups like the bourgeoisie or the proletariat; or leaders like Napoleon or de Gaulle. Sorel’s notion is more normative, and also more narrowly focused, in the sense that he is talking about how certain political ideals can help collective mobilizations to bring about revolutionary change. I think of myths as a much broader category, and they are not just about transformation: a powerful myth can also prevent substantial change (see the monarchy in Britain today!). I think myth is a useful concept for the social scientist because it opens up new avenues for analysis. Politics is too often thought about purely in ‘rational’ terms, as a function of interests – the concept of ‘myth’ is helpful to understand what role memory, imagination, and passion can also play in politics.

The New Bulgarian Government: A fresh beginning or more of the same?

Bulgaria’s parliament recently approved a new centre-left government, ending a three-month stalemate after the previous centre-right government resigned in February 2013 amidst widespread anti-austerity protests. Despite the seriousness of the task it faces, which includes addressing the protesters’ grievances and ensuring Bulgaria’s economic development, due to a lack of parliamentary majority, the new government is unlikely to bring any significant changes and distance itself from the previous one.

Davids Versus Goliaths: Can Palestinians, Greeks and Cypriots apply the same solutions to similar bargaining problems?

Like the queues in Qalandyia checkpoint and those in front of Laiki Bank, the demonstrations in Nabi Saleh and those in Syntagma Square seem worlds apart. And they are – a military occupation cannot be compared with austerity measures.

However, even though there are many differences between the daily lives of Palestinians and Hellenic nations, they face similar bargaining problems and decisions towards the current status quo. In order to consider if they could apply similar solutions to strive for a brighter future, drawing comparisons between these two situations might help us better comprehend the similar bargaining problems they face.