Do local elections matter? In Britain, like in many other countries, we often see them as crucial indicators of the future general election performance of political parties and their leaders. They also have national political significance. Local election success in 2009 brought good press for former Prime Minister David Cameron before his national victory a year later; huge losses in local elections in 2019 helped sink the leadership of his successor Theresa May. Yet, the methods used to study local elections in Britain do not provide a clear or consistent indicator of how well parties are doing nationwide or how they will go on to fair at future national polls. The 2022 local elections, for instance, provided just such a muddied picture. Commentators argued it as either a respectable victory for the opposition Labour Party or a mixed bag, with the Conservatives blunting Labour’s gains.

What then is the best way to use local elections to judge how parties are performing at the national level consistently and quantitatively? And how well does this success herald future general election victories? There are several approaches we might take. The first and most common method—and what national media often use—is to compare overall councillor gains and losses, or national vote share. This gives us a general overview of the election but is limited. Voters elect councillors to seats in local government every four years in the UK. These elections are staggered across the country annually, so the pattern of seats up for grabs at an election will typically favour one party over another.

The second method compares the results to when seats were last fought, four years ago. This means that we are comparing like-for-like but runs into the same problem when we try to make national inferences, compounded by the fact that we are looking across potentially different economic and social contexts. We are also comparing parties across different baselines: if a party did well four years ago, for instance, then it is harder for them to look like they have made gains after the coming election.

By far the most reliable, though least used, method is to extrapolate the local results out to a nationwide contest. We can do this using Colin Rallings and Michael Thrashers’ National Equivalent Vote Share (NEVS) data. This method takes results from seats where the three major parties—the Conservatives, Labour, and the Liberal Democrats (Lib Dems)—stood candidates. It then compares these individual results to a baseline: in this case the NEVS when those seats were last fought. Applying the mean change across these seats gives the NEVS for the that election. The advantage of this method is that it gives us a consistent national picture from disparate local results, telling us how well the parties would do if the local elections were to happen everywhere in the country (it excludes Northern Ireland), and allowing us to reliably compare results year-to-year.

What it takes to do well

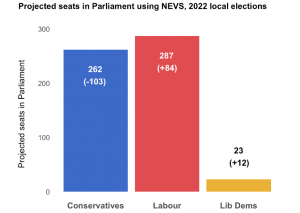

So how well did the parties do in 2022? In the NEVS, Labour won, securing 35 percent of the vote to the Conservatives’ 33. If this were replicated at a general election, assuming a uniform swing in each parliamentary constituency, Labour would win 287 seats to 262—an impressive increase but still 39 seats short of a majority in the House of Commons.

However, while there is a strong relationship between the NEVS and subsequent general election vote share, including when controlling for incumbency and party-specific effects, it is not always exact. Governing parties tend to underperform in the NEVS, and in the years leading up to their general election victories, successful opposition parties have consistently outperformed the party in government. Recently, Labour has been failing dramatically to do this.

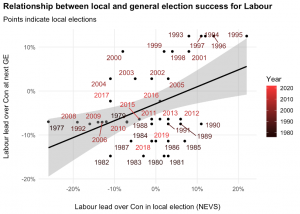

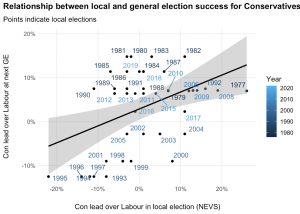

Graph by author.

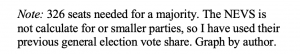

If we plot NEVS data over time, which has not yet been done with 2022 data, we see that opposition parties that go on to win nationally regularly score very highly in the NEVS. Over the past half-century, Britain’s national government has changed party only three times, in 1979, 1997, and 2010. In the four years preceding those elections, the winner achieved an average NEVS lead of around 14–16 percent. In the four years prior to 2022, Labour’s average lead has been minus 4 percent. Its 2 per cent victory in 2022 now looks like a hollow one.

Different standards of success

Even if Labour does not need to be dominant in vote share to win a future general election, it faces an uphill battle. While there is a linear relationship between a party’s vote share lead in the NEVS and its lead at the next general election, it is skewed heavily in favour of the Conservatives.

Graph by author

Graph by author

These two graphs show that Labour consistently underperforms at general elections relative to its local election success. Historically, for Labour to lead in vote share at a general election, it would have to gain a nearly 10 point advantage in the NEVS at preceding local elections. In contrast, the Conservatives could suffer an almost 10 point loss in the NEVS and still lead at the next general election (local elections four years from a general election are historically roughly equally good predictors of general election success than those one year before). This is partly a reflection of Labour’s historical underperformance at the national election. Still, it shows the mountain the party must climb. Worryingly for the party, the elections which have closely matched this trend have been the most recent ones.

All politics is local

There are caveats to these conclusions: the issue profile of a local election is not the same as a national election, turnout is far lower, and those who participate tend to be more politically engaged. This might give us some pause for thought when using local votes to forecast national competition. Even so, evidence from the UK and other countries shows that voters behave similarly in local and national elections. Local government in Britain is also much weaker than in most other rich countries, giving voters greater incentive to treat the vote as a referendum on the national government. That they often have implications for the careers of party leaders adds to this.

This does not necessarily imply that voters simply follow national preferences when voting in second-order polls like local elections, but it does mean that we should pay close attention to local results when considering national performance. More importantly, researchers and commentators need to adopt methods, like the NEVS, that allow for clear and consistent evaluations of success.