Some six months before Theresa May called a surprise general election, The Road to Somewhere was published. In it, David Goodhart argues that the old political divide, between left-wingers and right-wingers, has been superseded. The electorate, Goodhart claims, is now better divided between “anywheres” and “somewheres”. Peter Wiggins looks at the Goodhart argument in the context of the 2017 general election.

Of “Anywheres”, “Somewheres” and “Inbetweeners”

According to The Road to Somewhere, roughly 25% of the population are “anywheres” – they are mobile, metropolitan, liberal, tolerant, at home wherever they may be, and wary of group attachment. These voters are likely to be highly educated, and they tend to approve of “mass immigration,” subscribing, as Goodhart puts it, to “progressive individualism.” Roughly 50% of the population are “somewheres” – they tend to be provincial, communitarian and to be rooted in local identity and customs, valuing familiarity and security. They are less likely to be highly educated, and they wish to see the end of “mass immigration.” “Somewheres” are likely to perceive change “in terms of loss.” The remainder of the population — around 25% — are “inbetweeners” whose characteristics are split. Goodhart’s claims are based on polling data from the British Attitudes Survey and YouGov. The division may seem stark, and to be little more than an exercise in labelling. But, it should be said, the book itself is not without nuance.

Goodhart thinks that his new categorization can guide an analysis of the EU referendum vote. Most of those who voted Leave don’t belong among the “anywheres” as the data bears out. A study of voters’ social values provides a better indicator of how they voted than their political attitudes based on a left-right split. For instance, support for the death penalty was the most reliable predictor of voting Leave. Education levels seem to have been influential as well, 64% of those without formal education voted Leave, while two thirds of graduates, as well as four firths of those in full-time education, voted Remain.

Goodhart’s case is that, until the recent Brexit vote, the “somewheres” had been discriminated against. An “anywhere mindset” dominated public life. The “somewheres” are then cast as underdogs. All major parties represent “anywheres” argues Goodhart, and their detachment from the values of somewheres has engendered anger. It is this anger that led to Brexit.

Although his book centres upon the UK, Goodhart explains that it can also account for the victory of President Trump: Trump consolidated the somewhere vote in key electoral college states. Apparently, Goodhart’s new division illuminates the surprise results of two 2016 votes, on both two sides of the Atlantic, but what about June 2017’s General Election? Does Goodhart’s categorization effort offer new insight?

Campaigning for the “Somewheres”

Campaigning for the “Somewheres”

In many ways Theresa May sought to run for and represent the purportedly hitherto forgotten “somewheres.” Nicholas Timothy,May’s influential political advisor and chief author of the Tories’ manifesto, has his name in the credits of The Road to Somewhere. When Michael Gove wrote about Theresa May’s political ideology in The Times, he predicted that Theresa May would be the “somewhere” prime minister.

I expect the Conservative manifesto, and the Queen’s Speeches to follow, to be rooted in the concerns of those whom the writer David Goodhart has described as the citizens of somewhere rather than anywhere. Those who are rooted in specific communities, who aren’t living life from one Twitter storm to the next, who don’t have the reserves of capital, or connections, to be able to chase every new opportunity globalisation might provide.

It is not difficult to align the “somewhere mindset” with things that Theresa May has said. There was her hard-line approach to Brexit: “no deal is better than a bad deal”; and, straight out of the Goodhart playbook, “if you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere”. With the “somewhere” vote apparently making up a whopping 50% of the population, May may have thought she had struck electoral gold.

The Tory manifesto certainly had “somewhere” policy areas, such as proposals to increase the levy on firms employing overseas citizens, to restrict foreign takeovers, and, to support technical training for British citizens. Such measures were criticised by liberal Tories and by free market publications. On economics, May was accused of moving the Tories “to the left”. But Goodhart might say that the strategy was to move the Tories over to the anti-globalist concerns of the “somewheres”.

As is well known, the election was terrible for Theresa May’s Tories. May will be remembered for nothing if not a truly disastrous campaign. She lost her majority; and two days after the election, the head of Nick Timothy rolled.

The election was also a disaster for the pollsters and the political scientists. The vast majority of the polls got it very wrong; and many of the supposed “iron laws” of modern politics did not hold up. The young are supposed to be apathetic, yet they turned out in record numbers. Increases in turn-out are not supposed to favour one party over another; yet there can be no doubt that the increased turnout from 2015 hugely favoured Corbyn’s Labour. The campaign is supposed not to matter; yet Labour undoubtedly gained an enormous amount of support over its course. Britain had been supposed to be moving away from a two-party system; yet Britain’s two main parties captured more than four fifths of the vote. A left-wing Labour party is supposed to get crushed; yet Corbyn’s Labour gained 30 seats and 10% of the vote share. The party ahead on economic competence is supposed to win decisively; yet if May’s Tories won at all, for sure it was not decisive.

The Revenge of the “Anywheres”

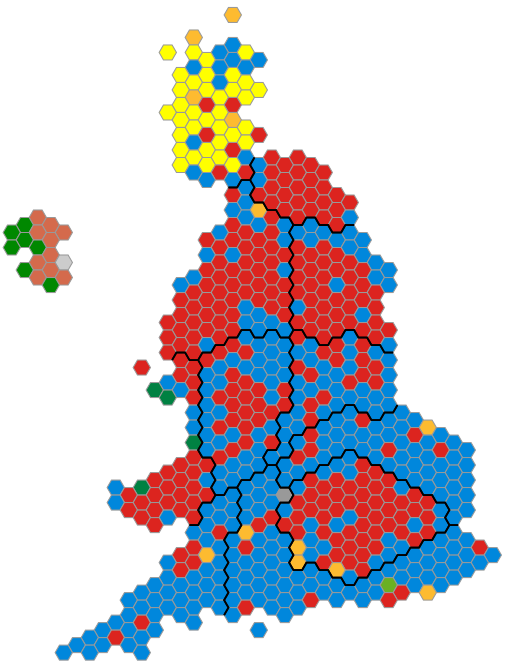

In all sorts of ways “somewhere vs. anywhere” offers an insightful and interesting prism through which to analyse the 2017 general election results. It can help to explain not only why some of the supposed iron laws of politics failed to hold, but also the changes in the electoral map from 2015.

The Tories gained 5.5% of the vote share from 2015, reaching an extremely high 42.5% vote share. And they garnered 57% of the 2015 UKIP vote. In 2015 13.5% of the country voted UKIP—the natural party of the “somewheres,” you might think. Wasn’t this exactly the kind of consolidation of the “somewhere” vote that May and Timothy were planning? Labour meanwhile gained just 17% of the 2015 UKIP voters.

The North East is the part of England that voted most decisively for Brexit. And here the Tories gained in June. In constituencies where over 60% of the population had voted Leave, the swing, of 0.8%, was in the Tories’ direction. Among DE voters (the “semi-skilled & unskilled manual occupations, unemployed and lowest grade occupations”) the Tories swing over Labour was 5%.

So far, so good for May and her attempt to get that “somewhere” vote. But it leaves us without an explanation of why the Tories went backwards in the House of Commons.

Part of the explanation relates to our voting system. A high vote share doesn’t mean much under First Past the Post electoral rules. In such a system, you have to gain ground on your opponents — and Labour achieved a very high vote share (40%) too. Labour did best in the areas with plenty of “anywheres.” In seats where over 55% of the electorate voted Remain the swing to Labour was 7%. Moreover, Labour made its biggest gains in the place that Goodhart identifies as the home of the “anywheres” —metropolitan London (where it got a 5.8% swing). Broadly speaking, Labour’s gains were in places with ethnic minorities, social liberals, students, and graduates.

All the small parties collapsed, to varying extents. The diminishing influence of the small parties, you might say, shows a polarised and divided country, perhaps confirming Goodhart’s introduction of his “anywhere vs somewhere” divide. In post-Brexit Britain, voters may have turned less to particular policy offers and more to tribal allegiance.

Of course, not speaking directly to the politics of General Elections, Goodhart could not have predicted how bad a campaign the Tories would run, or how good a campaign would be run by Labour. There is a point here about the influence of events in politics. One event can knock on to the next: if Brexit was the revenge of the “somewheres,” the election of 2017 was the revenge of the “anywheres”.

The Road to an Any- or Somewhere Future?

So should we now think of the U.K. as having started out on the “road to somewhere,” in Goodhart’s sense? Well, even if Goodhart’s book is of some use in understanding the outcomes of the June 2017 General Election, it seems unlikely that it provides us with very good a guide to the future. Reading the book back in January and then being told in May about the forthcoming snap election, you would think that May’s Tories had been set to clean up. On this, Goodhart is just as bad at predicting as the newspaper columnists. Given that the Tories went backwards, we need to remember not only our electoral system, but also the quarter of the electorate Goodhart labels “inbetweeners.” In the book, “inbetweeners” don’t get much attention, despite the fact that such a substantial group of potential swing-voters in the middle will be decisive for most races. No allowance is made for the possible appeal to them of a robust optimistic “anywhere” position, or a candidate with legitimate “somewhere” appeal.

In common with many political pundits, Goodhart simply writes off Corbyn. He calls Corbyn a “global villager” with an “old statist vision”. Yet, Corbyn himself is a lifelong Brexiteer; he is distinctly English and he could not possibly come from anywhere but England (however much he might like to). What is more, before he became Labour leader, Corbyn was famed for being, among other things, a “good local MP,” well known to the people of Islington. In his own way, Corbyn is just as rooted as anyone else, and then some. It might in some part have been this earthy appeal that spoke to British “anywheres,” not to mention the “inbetweeners.” “Decent populists” is Goodhart’s own description of “most somewheres”. To many “anywhere” voters, Corbyn himself perhaps came across as a “decent populist.” What exactly is a “populist”? – we might be left wondering.

At the end of the book, Goodhart makes the case that successful leaders of the future will be able to bridge the gap between the two value groups he identifies. As things stand, it is far from clear who that politician might be. If the 2017 election is anything to go by, it would seem not to be Theresa May or Jeremy Corbyn; though, just if we are allowed to combine the outlook of Goodhart’s “anywheres” with the discontent felt by his “somewheres,” we can embrace Corbyn’s vision of Labour as in the ascendancy.

With so much of the 2015 UKIP vote now embedded in the Tory Coalition, and with Labour now more officially a party of soft Brexit, it is very difficult to see how the next election will play out. Both parties have coalitions that are as diverse as they are fragile. Of course we don’t know when the next general election will be, still less what events there may have been ahead of it. A lot will depend on the economy and UK’s negotiations with the EU. There will be much to play for, on which Goodhart cannot be supposed to cast much light.