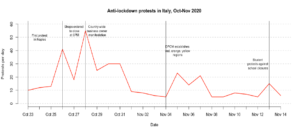

Italy was the first Western democracy to impose a country-wide lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite successfully curbing the number of infections in the first half of 2020, Italy saw its cases increase again in October, prompting Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte and local governments to announce new restrictions to curb the cresting second wave. Despite the clear memory of the significant death toll and warnings of the dangerous winter to come, however, these announcements have been met with opposition. On the evening of the 23rd October, thousands gathered in the streets of Naples to protest against the forced closure of shops and restaurants and the threat of a local lockdown. A group of about 300 people—including youth, extremist political groups, and football hooligans—escalated into a violent protest, attacking police officers, burning cars, and vandalizing private and public property. In the wake of the event in Naples, a wave of protests spread throughout the peninsula, prompting similar episodes of violence in Rome, Turin, Milan, and Bologna within a week. According to data collected from national and local newspapers and reported in Figure 1, 371 protests took place over the course of just three weeks. 1

Figure 1

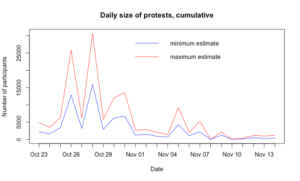

Figure 2 shows the cumulative count of participants per day, using a minimum and maximum estimate based on data reported in newspapers. The size of protests were quite significant in the first week of protests, with peaks on the 26th and 28th of October.

Figure 2

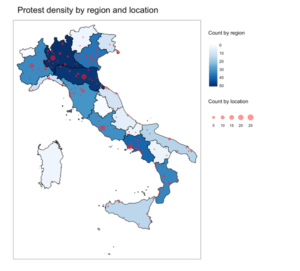

As Map 1 shows, demonstrations occurred across the entire peninsula, and all but 2 of 20 regions (Umbria and Valle d’Aosta) recorded at least one protest. The regions with the highest number of protests were Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, and Campania, while the cities with the highest number of protest events were Rome (22), Naples (21), Bologna (20), Milan (19), and Turin (15). Some of the cities with a disproportionately large number of protests relative to their population size are Reggio Calabria and Reggio Emilia, with 7 counts each.

Map 1

Even before the protests started, Italy’s Minister of the Interior, Luciana Lamorgese, issued a warning about the risk of a “hot autumn” (“autunno caldo”) as Italians’ economic conditions deteriorated in light of the first lockdown and the subsequent loss of jobs and income. Indeed, the spike in protest numbers is significant, especially when compared to the last twenty years of Italian political history, which have seen a relatively low number of demonstrations.2 However, the vast majority of these protests were peaceful, with violence happening only in 8.6% of cases—and often concentrated in large urban centres.

One potential reason for the protests’ relative peace may be the identity of the main actors: business owners and entrepreneurs. Historically, these actors are rare in Italian protests— which traditionally feature workers, trade unionists, and students 3. Business owners and entrepreneurs were present in 251 protests (or 68.6% of all events). Business owners said they took to the streets primarily to protest against their personal economic hardship, which a second lockdown threatened to make worse. Many business owners said that they had invested significantly in personal protective equipment and sanitary measures in their premises, only to be forced to shut down again. According to the recorded data, economic hardship was the core reason provided for participating in the protests (74.4% of cases), followed by the perceived curtailment of civil liberties (58%). Only in 29 protests did we see claims about the government’s undemocratic practices, with demonstrators using the catchphrase “sanitary dictatorship” (“dittatura sanitaria”), whereas in 36 cases, protesters contested the existence of COVID-19. On the balance, these figures suggest protesters are aware of the dangers posed by the pandemic but do not believe the government measures to address the second wave are appropriate.

Meanwhile, there are widespread fears that the protests, by attracting extremist groups like the football Ultras and criminal gangs, will furnish common cause and alliances of convenience as they generate escalating levels of violence. 4 These claims are only weakly supported by the data. More than one in every three protests experienced participation by politically motivated groups and not all of these groups were extremists. The most present organizations were right-wing parties, such as Fratelli d’Italia and the Lega, present in 54 occasions, followed by groups on the extreme right and left. However, radical groups from the left and right were present in 30 out of the 37 protests which took a violent turn. Perhaps more interesting is the practice of parliamentary political parties leveraging the protests as means of strengthening their popularity and voicing their dissent towards the government. In particular, the right-wing Fratelli d’Italia party seems to have followed this strategy, using protests as public evidence of waning confidence in government. For two other potentially subversive actors, organized football groups were present in 32 protests, and newspaper reports noted the presence of organized crime groups in three events.

Map 2

By December, Italy’s restive autumn served as harbinger for anti-government protests in Germany, France, and Spain, as COVID-19’s second wave gained force. 5 For those reasons, Italy may offer vital warnings about protests and political action in the shadow of global health pandemics. For one, the type of actors motivated to take to the streets may differ strongly from our historical expectations. In Italy, the aggrieved were not radicals but business professionals, who were desperate to voice their disapproval through peaceful and legal means. Further, COVID denial is, perhaps positively, not the main reason for protesting, as demonstrators instead reacted to the widespread financial costs of the government restrictions—abetting the common, if clichéd, aphorism at the heart of representative politics: “It’s the economy, stupid.” This may also suggest that the potential band aid solution, in the interim, would be increased economic transfers from government to citizens and their businesses as a way of keeping potential protesters at home. For Italy, however, these spot transfers and payments may fall short, given country’s extensive underground and informal sector. This represents a significant portion of the economy 6, that will be missing from the government’s official register. Finally, and most concerning, is the ability for protests to generate a kind of temporary public commons where peaceful protestors, often without previous experience of political dissent, will encounter and mingle amongst radical groups with expertise in violent political actions. Out of this miasma‚ riven by the precarity of Italy’s economic future‚ we may yet see new forms of (dangerous) political dissent.

- We coded all protests reported in the Ministry of Interior’s press release database between the dates of 24/10/20 and 15/11/20. The count of 371 is likely to be a conservative estimate, as even local newspapers tend to underreport protests with a small number of participants and/or demonstrations happening in small towns. Additionally, protests did continue after the 14th November, but the daily count is progressively reduced.

- The average of protests in Italy between 1990 and 2018 is 7 per year, according to Klein, Graig R., and Patrick M. Regan. “Dynamics of Political Protests.” International Organization 72, no. 2 (2018): 485. Della Porta and Tarrow for the “hot” 1966-197, coded 53 protests per month. Della Porta, Donatella and Sidney Tarrow. “Unwanted children: Political violence and the cycle of protest in Italy, 1966–1973.” European Journal of Political Research 14, no. 5‐6 (1986): 607-632.

- Tarrow, Sidney G. Democracy and disorder : protest and politics in Italy, 1965-1975. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

- This widespread belief can be seen in titles such as “Regia unica dietro gli scontri” [“Behind the clashes there was a coordinated plan”], Corriere Torino, 28 Oct 2020, p. 1-2.

- “Lockdown Backlash: Violent Protests Sweep across Europe”, The Daily Express, 27 October 2020. https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1352769/coronavirus-lockdown-protests-Italy-Europe-covid-pandemic-Spain-France-Germany

- More than 3 millions of individuals work in informal economy according to the estimates of the Italian central bureau of Statistics (ISTAT, 2018).