After much speculation about the future of the Japanese Navy, it was announced in early December that the Izumo-class helicopter carriers will be converted to aircraft carriers. This will require a substantial reconstruction of the two ships as well as the purchase of F‑35B fighter jets to comprise the carriers’ airwings. It is likely that 100 additional F-35 aircraft will be ordered to further bulk up Japanese aerial capabilities.

This change is important for three reasons, firstly, Japan has not operated aircraft carriers since World War Two, secondly, they are being commissioned to contest increasing Chinese control of the northwest Pacific, and thirdly, because aircraft carriers are also under construction in the United States, Britain, China and India. We appear to be in the midst of a naval arms race which is likely to impact major power relations in south and east Asia.

The new Japanese navy

There is little doubt that the Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, wishes Japan to normalise its military. Since 1952 and the enaction of the post-war constitution, Japan’s military posture has been firmly rooted in defence. In practice this has meant three things, firstly, that offensive weaponry has not been acquired or developed, secondly, that there are strong restrictions on Japanese forces serving abroad, and thirdly, that nuclear weapons will not be pursued.

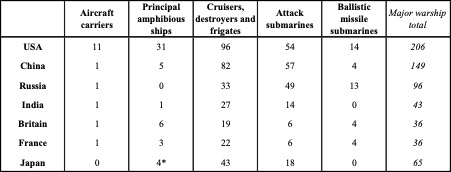

The move toward the acquisition of offensive weaponry has been coming, and there is no doubt that aircraft carriers are chiefly offensive in nature. Yet, it is also true – and often missed – that the Japanese Navy is already formidable. Japan has 18 attack submarines and plans to buy more, as well as more than 40 major surface combatants comprising modern destroyers and frigates (see Table 1 for comparison).

To put this number in context, both Britain and France have half as many of each, though their attack submarines are nuclear powered. The crucial change these aircraft carriers suggest is the operation of Japanese naval fleets beyond the range of land-based aircraft, meaning Japan could return to operating a blue-water navy for the first-time since World War Two.

Table 1: A comparison of major power naval strength

Note: Data modified from International Institute for Strategic Studies, Military Balance.

*Two of these vessels are to be refitted as aircraft carriers.

Contesting increasing Chinese dominance

The balance of capabilities has rapidly altered in the region, with the result that Japan has recognised the need to upgrade its own capabilities as it appears the US may be unable to dominate the western Pacific without allied support. As Table 1 shows, the Chinese navy is much larger than the Japanese, and though it appears that Japan has rough parity in amphibious forces, China also operates more than 40 landing ships, most of which are more than 4,000 tonnes and were commissioned over the last 15 years.

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies Military Balance 2018, China’s investments in shipbuilding since 2000 mean that it has exceeded the outputs of the next three principal regional navies (Japan, India, and South Korea) combined in terms of tonnage commissioned. Moreover, and perhaps more surprisingly, over the 2015-17 period China significantly out produced the USA, launching more than 350,000 tonnes to 200,000 tonnes.

The wider race for aircraft carriers

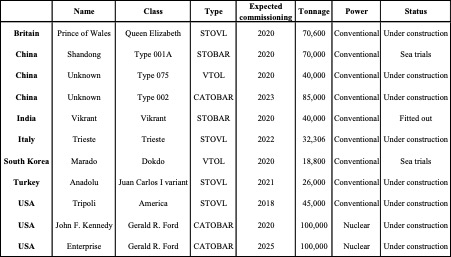

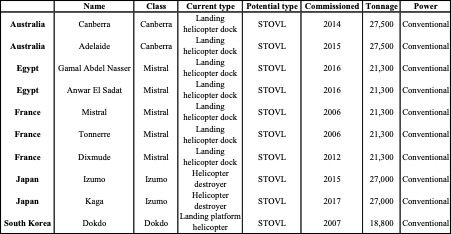

Whilst Japan is clearly responding to the rapid increase in capabilities of China, the acquisition of aircraft carriers is not limited to East Asia. Six other countries currently have aircraft carriers under construction (see Table 2) and several others operate ships which could rapidly be refitted to operate jet aircraft (as Japan is planning, see Table 3).

Whilst both Britain and the United States are not new to operating aircraft carriers, the new British vessels are the largest warships Britain has ever operated and the British Ambassador to the United States, Kim Darroch, has publicly stated that they will be deployed to the Pacific in support of freedom of navigation operations. This marks a significant move by Britain to engaging militarily ‘East of Suez’ once more and has led to a new naval base being opened in Bahrain to support the aircraft carriers.

The most consequential moves have come from China, India and Turkey. Though India has operated aircraft carriers since 1961, these vessels have never previously been built in India. Until the Vikramaditya entered service in 2013, both prior vessels were of British World War Two origin. Moreover, the Indian Navy will soon operate multiple carriers, with a clear strategic aim of being able to operate fleets simultaneously in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal. The expansion of military bases in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands also marks a shift towards forward deployment, with the clear purpose of being able to monitor naval traffic passing through the Strait of Malacca, and to potentially contest control.

The Chinese Navy is expanding rapidly as noted above, with multiple aircraft carriers under construction, which will enable the deployment of fleets beyond land-based air cover. Though the Turkish navy remains modest when compared to the others examined here, the move to operate an aircraft carrier is significant in that the country has never before operated one. The Anadolu could give Turkey the ability to deploy forces abroad independent of allies, a significant move and one which could have important consequences for its role as a regional power in the Middle East.

Table 2: Aircraft carriers under construction or undergoing sea trials

Note: STOVL = short take-off and vertical landing; STOBAR = short take-off but arrested recovery; VTOL = vertical take-off and landing; and CATOBAR = catapult assisted take-off but arrested recovery. South Korea’s Marado and China’s unknown Type 075 class are both expected to enter service as helicopter carriers, but as with the ships listed in Table 3, could be refitted.

Table 3: Potential refits

Note: Except for France, these refits have been publicly suggested, though only Japan has announced firm plans for conversion. Refitting would also require the purchase of suitable aircraft, which, given the size of these vessels, would need to be short take-off and vertical landing. Japan has announced the purchase of such aircraft, the F-35B, whilst both Australia and South Korea have already ordered F-35As, raising the possibility of F-35B purchases.

Conclusion

Naval rivalry in the Pacific and Indian Oceans is part of increasing tensions between states in the region. These have been driven by the economic and military rises of India and especially China, but also the relative disengagement of the United States, which has encouraged traditional allies like Japan and South Korea to increasingly take security into their own hands. This increases the number of relevant players in strategic bargaining in the region, which likely increases the risk of miscalculation. The next decade is likely to see a further shift away from relying on the United States in trying to ‘hard balance’ the naval capabilities with China, which will necessitate South Korea, Japan and India to continue their own naval build-ups. Unless limitations can be agreed on, the naval arms race, therefore, is likely to ramp up further.