To what extent is the international community truly international? And, to what extent are non-Western norms and practices excluded? The choice of language in international relations is one important aspect of this broad topic. Each international organization has official languages. The United Nations, for example, has six official languages, and the European Union 24, though only three – English, French and German – are used in procedures of the Commission. The choice of language is partly driven by the need to communicate to the widest number of people, but it also has an endogenous relationship with state power. Powerful states promote the languages they use, and in turn, others must learn their languages to participate, propagating their power.

An important aspect of the choice of language is how names are rendered. Specifically, cultures vary on the order in which the forename and surname is presented. Here, I examine the ‘westernization’ of people’s names, with a specific focus upon Japan. In May 2019 Kono Taro¹, Japan’s Foreign Minister, asked that international media begin formatting Japanese names as surname-forename, the Japanese convention, rather than forename-surname, the Western convention. Utilizing Factiva, a news aggregation service, and Google Trends, I explore how the name of Abe Shinzo, Japan’s current and longest serving Prime Minister, has been rendered across time and space. I find an uptick in the use of the Japanese naming convention post-May 2019, but that the Western convention still grossly exceeds the use of the Japanese convention. It is also unclear how sustained any change has been, or will be. This highlights the hierarchical nature of international society in terms of the social norms it has utilized and the difficulty of altering these conventions.

Global media

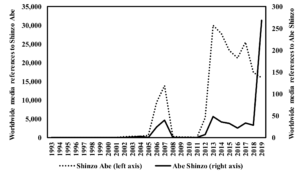

Global media references to Abe Shinzo and Shinzo Abe can be counted utilizing Factiva. Figure 1 plots all references to the two different formulations from 1993 (when he was first elected as an MP) though to the end of 2019. The count is of articles² per year, not of the references themselves, to prevent a single article with multiple references from skewing the data. Unsurprisingly, both formulations jump in frequency for the periods that Abe Shinzo has been Prime Minister (September 2006 – September 2007, and December 2012 onwards). A large spike can be seen in references to Abe Shinzo in 2019, perhaps reflecting the appeal to adopt the Japanese naming convention. However, the disparity in references is so large, two different axes to display them on the same chart. In 2019, there were 269 articles referring to Abe Shinzo, a huge jump from the 28 in 2018 but still dwarfed by the 15,993 articles referring to Shinzo Abe.

Figure 1: A comparison of global media references to Abe Shinzo and Shinzo Abe, 1993-2019.

To compare the trends in the two formulations over time Figure 2 plots the natural log of the number of articles in global media referring to the two formulations. The two generally track each other suggesting that references to the two have been consistently proportionate. However, the proportion does change in 2019 when the use of Abe Shinzo significantly increases.

Figure 2: Natural log of global media references to Abe Shinzo and Shinzo Abe, 1993-2019.

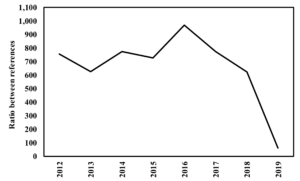

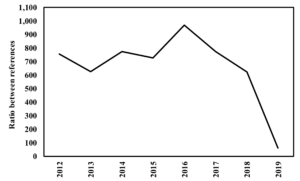

This trend appears to be confirmed by Figure 3 which plots the ratio of references to the two. Over the period of Abe Shinzo’s second period as Prime Minister, from 2012, the ratio has remained reasonably constant at around 750 times³ more references to Shinzo Abe than to Abe Shinzo. In 2019, by contrast, this plummeted to just 59 times more references. This suggests that global media have responded to Kono Taro’s request, though the absolute number of articles using Abe Shinzo is still small.

Figure 3: Ratio between references to Shinzo Abe and Abe Shinzo in global media, 2012-2019.

Note: Data series truncated to 2012 since in some years references to both or to Abe Shinzo were zero.

Public internet searches

By examining public internet searches through Google Trends, the question can be examined from a different angle, that is, whether individual behaviour and understandings have been altered by Kono Taro’s request. Individuals have long been ignored in international relations given the focus on policymaking. Though the causal mechanism linking individual preferences to foreign policy outcomes is long, access to information and foreign travel is more prevalent. As a result, the public understandings of other countries are greater than in the past. Individual understandings of international relations, therefore, are more relevant than they’ve ever been, enabling citizens to better respond to the international actions of their leaders.

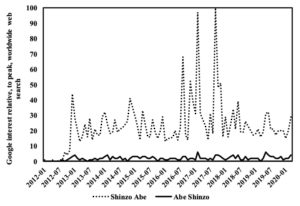

I used Google Trends to examine whether the public responded to Kono Taro’s request. Figure 4 compares trends in searching for the two names from January 2012 through to the end of March 2020, the approximate period of his second spell as Prime Minister. As can be seen, references to both spike when he was elected in November 2012, and then jump again in the lead up to and in the aftermath of the snap election called in late 2017. Throughout, Shinzo Abe remains far more commonly searched than Abe Shinzo. However, there is a distinct spike after May 2019 in Abe Shinzo (and Shinzo Abe) which does suggest that in the aftermath of Kono Taro’s request that public search patterns did change. It also appears that shortly afterwards the pattern returned to its prior position.

Figure 4: Global web searches relative to peak value, January 2012 – March 2020.

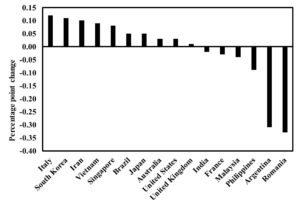

This can be investigated more fully by comparing references before and after Kono Taro’s request by country. Figure 5 compares the percentage point change in references to Abe Shinzo by country for the 45 weeks⁴ pre/post request. To explore this, I first compared references to the two name formulations by time period. This returns a percentage value for the two names by country. The values for the two years can then be compared and are relative to references to Shinzo Abe in that year. In this chart, only countries with values for both years⁵ and change between the two years are included. Positive change indicates an uptick in references to Abe Shinzo, with negative indicating the opposite. As can be seen, ten recorded positive change, which suggests that in several countries the public did alter their search behaviour post-request. It is unclear if this will be sustained, though. Interestingly, six countries recorded a negative change, two strongly so. This is surprising and could be because any change to small values results in large percentage point shifts. For instance, searches in Argentina for either name formulation may be reasonably small. The shift toward searching for Abe Shinzo may be drowned out by even a small shift in interest in the PM of Japan more generally.

This can be investigated more fully by comparing references before and after Kono Taro’s request by country. Figure 5 compares the percentage point change in references to Abe Shinzo by country for the 45 weeks⁴ pre/post request. To explore this, I first compared references to the two name formulations by time period. This returns a percentage value for the two names by country. The values for the two years can then be compared and are relative to references to Shinzo Abe in that year. In this chart, only countries with values for both years⁵ and change between the two years are included. Positive change indicates an uptick in references to Abe Shinzo, with negative indicating the opposite. As can be seen, ten recorded positive change, which suggests that in several countries the public did alter their search behaviour post-request. It is unclear if this will be sustained, though. Interestingly, six countries recorded a negative change, two strongly so. This is surprising and could be because any change to small values results in large percentage point shifts. For instance, searches in Argentina for either name formulation may be reasonably small. The shift toward searching for Abe Shinzo may be drowned out by even a small shift in interest in the PM of Japan more generally.

Figure 5: Percentage point change in references to Abe Shinzo compared with references to Shinzo Abe, 45 weeks pre and post 21st May 2019.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The data presented here suggests that some change has been observed post-Kono Taro’s request for both the global media and global public. Of course, it is unclear if this will be sustained. Habits take time to change, and news organizations would likely need to change their style-guides to ensure that this takes root and shapes public behaviour in the long term.

This also tells us important realities about international relations. Firstly, name conventions matter and the choice of one over another reinforces social hierarchies born of language choices. Secondly, it is difficult to elicit change as formal and informal institutions, both public and private, have significant memory and momentum. What remains unclear is whether the difficulty in eliciting change is harder for non-Western states even as they grow in their power on the world stage.

¹Formatted here in the Japanese convention.

² Factiva covers 32,000 sources, across 200 countries, in 28 languages

³ The mean value for 2012-2018 is 749 with a standard deviation of 108.

⁴ Specifically, 21/05/2019 – 01/04/2020 (post) with 15/07/2018 – 21/05/2019 (pre).

⁵ 50 countries, with representatives from every continent but Africa, had a value for both years.