How can we best promote legislative strengthening in new democracies? In a previous article, I talked about a new research project that aims to fill some of the gaps in our knowledge about democracy promotion. That project aims to do more than say ‘context matters’. We want to know what works where and when, and why it does so. This week we’re taking our first steps in that direction with the release of a new policy paper. Nic Cheeseman and I argue that parliamentary strengthening involves several trade-offs. Democracy promoters can’t avoid them, but they can learn to navigate them more effectively. Our policy paper – built on the experience of the Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD) – provides a framework that helps to do this.

Two trade-offs

WFD’s experience reveals two key trade-offs in parliamentary strengthening.

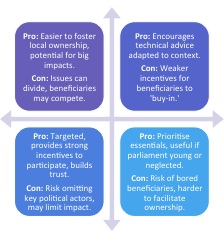

Issue-based vs institutional approaches

Issue-based approaches focus on one or more substantive topics, such as HIV/AIDS. Institutional approaches focus on technical and procedural issues, providing participants with the basic skills and knowledge necessary to make parliaments work. Institutional approaches have a bad reputation; they make it harder to facilitate local ownership because they don’t provide local actors with clear incentives to ‘buy in’ to reforms. In light of this, perhaps our most important finding is that neither approach makes it impossible to facilitate local ownership, nor does either one guarantee it. It’s easier to achieve with an issue-based approach. That’s precisely why they’ve become so popular. Yet sometimes institutional approaches are exactly what beneficiaries want.

Narrow vs inclusive approaches

Some parliamentary strengthening programmes have a narrow scope; they’re restricted to MPs and parliamentary staff. This focusses limited resources on the most important actors but risks excluding key political players who could block reforms. As a result, programmes increasingly attempt to bring in a broad range of actors. Often this includes local NGOs and civil society. More rarely it includes political parties. This gets potential veto-players on board. Unfortunately it also creates more opportunities for disagreement and risks stretching resources too far.

These trade-offs are illustrated in Figure 1, and explained in more detail in our policy paper. A point worth noting here is that they are not absolute. In larger programmes, different approaches can be combined. In longer programmes, different approaches can be employed over time. These trade-offs aren’t binary choices, they’re choices about where to position a programme along two spectrums.

One guiding principle

Successful navigation of these trade-offs means identifying which ones are worth it. To do this, we can use adaptation to political context as a guiding principle. However, context is a compass that doesn’t always point in the same direction. To translate our guiding principle into something more concrete, we focus on to two aspects of context that have a particularly strong influence on whether a trade-off is worthwhile.

The age of the legislature

Parliaments can be young because they’ve only just been established, or ‘born again’ because there’s been some sort of fundamental change in the nature of their role. In young legislatures institutional approaches help to build strong foundations; staff and MPs often respond to them with surprising enthusiasm. In older parliaments, institutional approaches tend to be seen as boring, so the interest generated by issue-based approaches is more valuable. The age of a parliament also shapes the impact of decisions about who to include in a programme. Younger parliaments are often characterised by significant distrust between MPs and CSOs. This makes inclusive approaches harder to implement, but also means they can deliver greater rewards.

The nature and extent of social cleavages

Democracy promoters are almost always working in divided societies. It’s the nature and extent of these divides, not simply their existence, that affects the costs and benefits of different trade-offs. This is most obvious where they’ve been linked to political violence or civil war. In such contexts programmes that are not inclusive risk – at best – being perceived as illegitimate, and – at worst – exacerbating existing social tensions. Where parties are organized on a programmatic basis, rather than around identity, it can be difficult to employ an issue-based approach while avoiding perceptions of bias. In contexts where political actors – be they parties or civil society – are organized around identity, programmes that deal with substantive topics often have a better chance of success.

Constraints and questions

WFD’s experience makes it clear that the funding environment can constrain successful navigation of the trade-offs discussed above. Democracy promoters respond to want donors want. This means that donors should avoid endorsing a single ‘correct’ or ‘preferred’ approach. They need to recognise that different strategies make sense in different contexts. Successful legislative strengthening requires – over the lifetime of a parliament – a mixture of approaches.

WFD’s experience also reveals that constraints can have unanticipated positive effects on parliamentary strengthening programmes. WFD’s most innovative programmes have often been responses to poor security. In some cases, poor security forced WFD to include local NGOs, not simply as beneficiaries, but as local partners responsible for putting programmes into practice. This reveals that innovation is the product of necessity. It occurs when democracy promoters are forced to take risks. This has clear policy implications: donors who want to see innovation must be more tolerant of risk.

These last few points expose some important questions that remain unanswered:

- How can donors encourage democracy promoters to use best-practice without mandating a single ‘correct’ approach? How do we stop lessons learnt from becoming one-size-fits-all solutions? Where can democracy promoters get the evidence they need to demonstrate that their proposed approach is the best fit for a particular case?

- Can accountability and innovation be reconciled? How can donors balance pressure to produce results with tolerance for failure when innovative programs don’t succeed? What should democracy promoters do differently to convince donors that risks are warranted?

- Once they’ve identified an intervention that’s appropriate for the political context, how can democracy promoters persuade funders and beneficiaries to support it? To what extent should the choice of intervention be shaped by what other projects and programmes have been done in the past, or are being conducted now?

These are questions where we’d like your input. You can get in touch via the comments section below, or via the Parliamentary Strengthening UK Community of Practice.