Ever since the Conservatives’ surprise win of a Parliamentary majority in the 2015 general election, the EU referendum has been at the centre of public debate. There has been much speculation about how many Conservative members of parliament (MPs) would back Brexit. Now David Cameron’s renegotiation has been concluded, MPs are free to choose sides in the referendum debate. Ever since, scores of Conservative of MPs, including the Mayor of London and six Cabinet Ministers, have endorsed the Leave campaign. Other MPs have sided with the Prime Minister and the Chancellor in backing Remain.

My DPhil research focuses on the position of members of parliament with regards to Europe. In this article I use my own dataset of Conservative MPs to consider two issues.

- How many Conservatives back each side in the referendum debate?

- Why are MPs backing different sides in this debate?

How many Conservative MPs are on each side of the referendum debate?

In order to obtain the numbers of Conservative MPs backing each side I have used pre-existing media attempts at classifying MPs[1], and supplemented this with my own research.

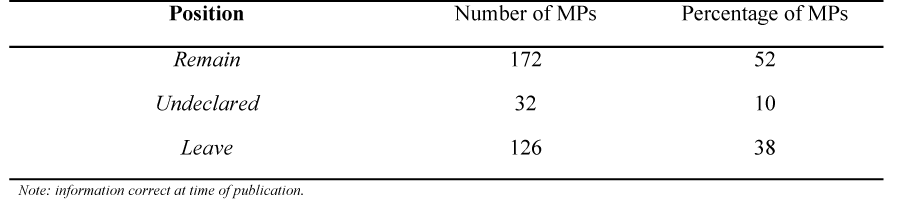

Table 1 and figure 1 below details how Conservative MPs have split over the referendum. The numbers show that whilst a majority of Conservatives back Remain, a substantial number support leaving the EU. This is line with my prediction, from a previous blog post last year, that over a third of the party would back Brexit.

Table 1 The position of Tory MPs on Brexit

Why are MPs adopting different sides in the referendum debate?

I have used these numbers as part of a logistic regression analysis of the positions of Conservative MPs on Brexit in order to try to explain why they have chosen their stance on the referendum.

Below I will argue that the following factors explain the position of MPs on Brexit:

- Nationalism

- Career interest

- Community/personal self-interest

- Electoral reasons

- Demographic differences between MPs

Nationalism

There are two results from my statistical analysis that suggest that nationalism is related to Euroscepticism.

Firstly, supporting Brexit is strongly associated with social conservatism. Those supporting Leave are more likely to oppose gay marriage and abortion, and to support the death penalty. The reason for this could be that MPs perceive European integration, particularly the European Court of Human Rights, as a socially liberal project.

However, a more likely link between social conservatism and Euroscepticism is nationalism. Both the political science and political psychology literatures have established a link between social conservativism and nationalism.[2] The specific literature on the Conservative party has also established a link between socially conservative attitudes and Euroscepticism.[3]

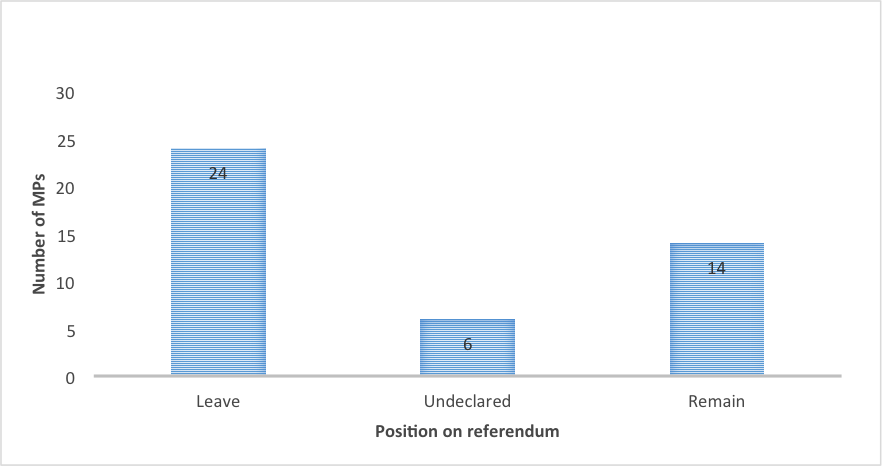

Secondly, MPs who have served in the military are more likely to support Leave. A majority of Conservative MPs with military experience want to leave the European Union and less than a third want to remain. There is much academic literature that shows that military personnel tend to be more patriotic/nationalistic than the civilian population[4].

Figure 1 The referendum stance of ex-military MPs

Career interests

There is also plenty of evidence in the statistics that MPs might be motivated by career aspirations. Although adopting positions on the referendum is formally unwhipped, the leadership has been seeking to gain the support of MPs for staying in the EU. Therefore it is in the interests of ambitious career-minded MPs to support Remain to improve their chances of promotion. The ministerial appointments after Iain Duncan Smith’s resignation serve to illustrate this, as all three appointments went to Remain MPs.

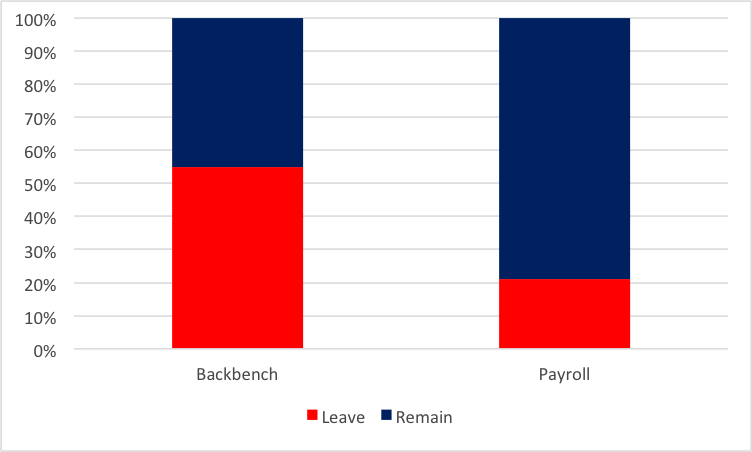

There are three main pieces of evidence from the statistics that suggest that career motivations are important. Firstly, there is clear gap between the front- and backbenches on the European issues (see Figure 2). Of the MPs who have so far declared a position, a majority of backbenchers have backed Leave, while the vast majority of the payroll have backed Remain. This relationship is still significant even when a range of other factors have been controlled for.

Figure 2 Difference in referendum support amongst payroll/backbench MPs[5]

Secondly, less experienced members of Parliament are less likely to support Brexit choosing either to back Remain or sit on the fence. These MPs will have ambitions of climbing the greasy pole and may have chosen to back Remain to satisfy Cameron or may have chosen to sit on the fence in case a Leave candidate such as Boris Johnson or Priti Patel wins the leadership election. Longer-serving MPs by contrast have fewer incentives to please the leadership as they may have already have been sacked, resigned or overlooked for government office and are thus freer to decide according to their personal beliefs.

Thirdly, the people who the media dub “professional politicians” or “career politicians” are more likely to support Remain. I am defining a career politician as anyone who has work as a special advisor, for an MP or for the central party before entering Parliament.[6] 64 per cent of career politicians back Remain compared to only 48 per cent of other MPs. As career politicians are less likely to have had successful careers outside of Westminster they have more incentives to strive for a frontbench role.[7]

Community self-interest

Community self-interest is another factor that affects the decision of MPs on the referendum. Politicians are choosing their sides based on the interests of the communities they are from.[8] The most notable evidence of this is that MPs with an agricultural background overwhelmingly support Remain. Farming interests have largely been opposed to Brexit as it could threaten the subsidies they receive under the Common Agricultural Policy, and their ability to recruit cheap migrant labour.[9] This will affect MPs with agricultural backgrounds as most, if not all of them, will either have shares in farming companies themselves and/or strong links to agricultural communities.

Electoral interests

Surprisingly, my statistics show little difference between Leave and Remain MPs in terms of constituency variables. The two groups have an almost identical average majority and there is no statistical difference between them on any of the constituency demographics I tested for[10].

However, there is one statistically significant result that suggests that constituency factors and re-election concerns might be affecting MPs’ positions: MPs elected in seats with higher levels of UKIP vote share are more likely to be uncommitted on the referendum. It may be that some MPs who are torn between the Prime Minister and a Eurosceptic constituency have chosen to be strategically noncommittal.

Educational differences between MPs

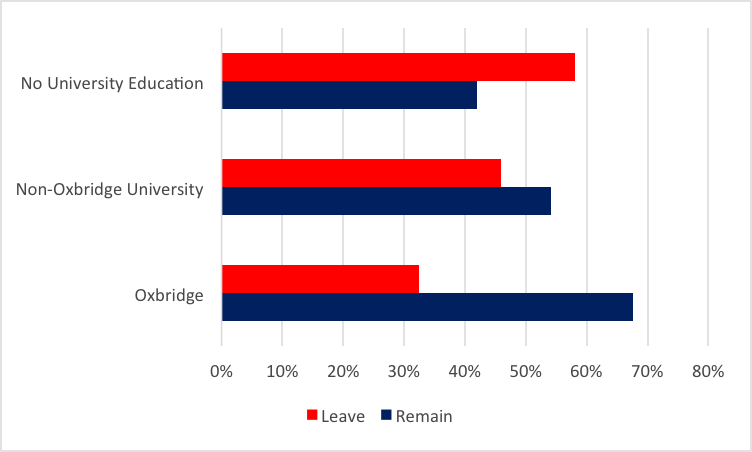

Finally, another factor that seems to account for the fact that MPs adopt different positions on the EU is educational differences between MPs (Figure 3). There is a long-standing trend within the Parliamentary Conservative Party that privately schooled and Oxbridge educated MPs are more likely to be socially liberal and less Eurosceptic than their state-schooled and non-Oxbridge educated colleagues.

My statistics show that this trend has continued in relation to university, as Oxbridge-educated MPs are more likely to support Remain than other Conservative MPs. The group most likely to back Brexit are those with no university education. The graph below illustrates this.

Figure 3 MPs stances on referendum according to University education[11]

The most likely reason for this is socialization. Socialization refers to “the process by which a person learns to function within a particular society or group by internalizing its values and norms”.[12] This could either be linked directly to education, meaning that attending Oxbridge gives future MPs a less Eurosceptic worldview; or it could be linked to class, as Oxbridge-educated MPs are more likely to come from privileged backgrounds.

Summary

A wide variety of factors appear to have influenced how the Conservative Party has split on Brexit. This reflects the fact that MPs are often faced with conflicting pressures, such as the party leadership, constituency, and personal conscience, when making political decisions.

The two questions this poses for the post-referendum Conservative Party are: can they put divisions over Europe to the side; and how will it affect the next Conservative leadership election?

Notes

[1] I have used three principal existing attempts to classify Conservative MPs. These include: Conservative Home: http://www.conservativehome.com/parliament/2016/03/europe-how-conservative-mps-break-down-2-three-in-four-brexit-supporters-are-backbenchers.html and http://www.conservativehome.com/parliament/2016/03/europe-how-conservative-mps-break-down-1-over-half-those-backing-remain-are-on-the-payroll.html; Guido Fawkes: http://order-order.com/2016/02/21/dozens-more-tory-mps-declare-for-remain/; and BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-35616946.

[2] On the political science literature see: Hooghe and Marks (2009). On the political psychology literature see: Smith et al (2011).

[3] See Webb and Bale (2014); Heppell (2013); and Berrington and Hague (1998).

[4] See for example Franke (2001) and Dorman (1976).

[5] Undeclared MPs omitted. Payroll includes Parliamentary Private Secretaries (PPS).

[6] This group consists of 64 MPs (19 per cent of the total Parliamentary Party).

[7] Some MPs classed as career politicians in the dataset have worked only briefly in politics and have had successful careers outside of the political arena.

[8] These are not necessarily the communities they represent in Parliament.

[9] For an example of farming concerns see: “Who will pick our fruit?” Worried farmers fear for future if UK quits the EU,” The Observer [online], available at: http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/jun/13/farmers-fear-eu-referendum.

[10] To be more precise, there was no statistical difference between the two groups in any of the bivariate models at the 95% level of significance. Demographic variables tested for include: employment status variables, population density, religion adherence variables, country of birth variables, ethnicity variables, age variables, and academic qualification variables.

[11] This does not include MPs who have not declared their stance.

[12] Oxford English Dictionary definition: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/183747#eid21929417.

References

Berrington, H. & Hague, R (1998) “Europe, Thatcherism and traditionalism: Opinion, rebellion and the Maastricht treaty in the backbench conservative party, 1992–1994”, West European Politics, vol. 21(1): pp. 44-71.

Dorman, J.E., 1976. ROTC Cadet Attitudes: A Product of Socialization or Self-Selection?. Journal of Political and Military Sociology, vol. 4(2), pp. 203-216

Franke, V.C., 2001. Generation X and the military: A comparison of attitudes and values between West Point cadets and college students. Journal of Political and Military Sociology, vol. 29(1): pp. 92-119.

Heppell, T. (2013), Cameron and Liberal Conservatism: Attitudes within the Parliamentary Conservative Party and Conservative Ministers. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, vol. 15: pp. 340–361.

Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2009). A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration: From Permissive Consensus to Constraining Dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, vol 39: pp. 1-23.

Smith, K. B., Oxley, D. R., Hibbing, M. V., Alford, J. R. and Hibbing, J. R. (2011), “Linking Genetics and Political Attitudes: Reconceptualizing Political Ideology”. Political Psychology, vol. 32: pp. 369–397.

Webb, P. and Bale, T. (2014), “Why Do Tories Defect to UKIP? Conservative Party Members and the Temptations of the Populist Radical Right” Political Studies, vol. 62: pp. 961–970.