On the 28th of October 1940 the Greek government rejected Benito Mussolini’s ultimatum demanding that Axis forces were given free entrance from neighbouring Albania and allowed to occupy strategic locations around the country. After the war, this momentous event in the history of modern Greece – popularly known as the No Day – became a national holiday, celebrated annually with impressive military and student parades.

On the 28th of October 1940 the Greek government rejected Benito Mussolini’s ultimatum demanding that Axis forces were given free entrance from neighbouring Albania and allowed to occupy strategic locations around the country. After the war, this momentous event in the history of modern Greece – popularly known as the No Day – became a national holiday, celebrated annually with impressive military and student parades.

Fourteen years ago, one such parade had to take place in a town near Thessaloniki. As a tradition, the best student in the local high school was expected to bear the Greek flag. The best student, though, was not Greek. He was an Albanian immigrant.

Pupils, parents and citizens throughout Greece rose in anger: despite his achievement, how could a non-Greek, an alien, a non-citizen at that, be allowed to carry the national colours? The government, the main political parties and the teachers’ union stood behind the excellent Albanian student but the boy responded to the growing commotion by choosing to step aside, allowing a Greek pupil to carry the flag.

Three years later, the same Albanian – having now distinguished himself as the best graduating student of his school – was again elected to bear the colours in the Greek national holiday parade. The public outcry, in this instance, grew even wider and sharper than earlier. The young man, for a second time, decided not to accept the honour but pass it on to a native schoolmate instead.

The volcanic public discourse surrounding these events had nationality, citizenship and ethnic origin at its centre. Blood, heredity, and even DNA, became salient elements of the debate – pitted against the qualities and achievements of the person, his or her social integration, active participation in and contribution to the Greek scheme of life. ‘What makes one truly Greek: one’s Hellenic outlook, behaviour and genuine belief in Greekness, one’s abilities and success in Greek society and/or one’s historical roots and genetic ancestry?’ was a question resounding loudly across the country and the region. Is it nature or nurture, a cocktail of the two, or perhaps something greater than that, which makes us genuine sons and daughters of a country, a nation or a people?

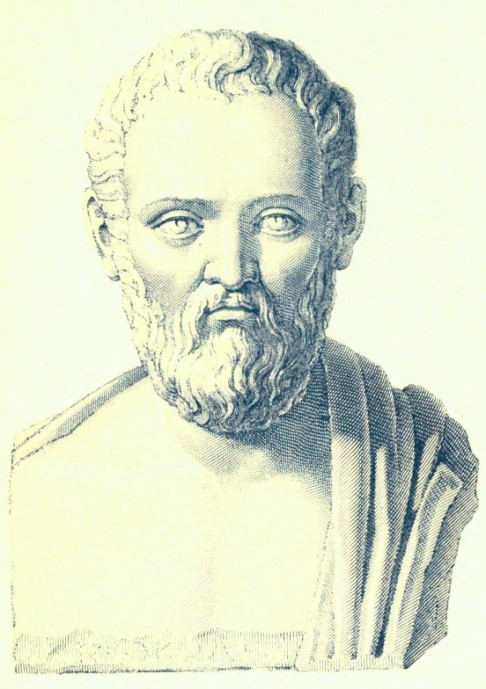

The perennial echo of this problem was picked up by the then president of the Greek Republic who, in defence of the Albanian student, quoted a line from a famous work by the great Athenian rhetorician Isocrates. “[Athens]”, the ancient man of letters writes in his Panegyricus, “has brought it about that the name Hellenes suggests no longer a race but an intelligence, and that the title Hellenes is applied rather to those who share our culture than to those who share a common blood”.

This twenty-four centuries old fragment has proven to be rather elusive to interpret. The question of national identity and affiliation with a political community, however, remains ever so vibrant not just in Greece and the Balkans but also in the UK and across Europe. Distilled and intensified, the two-headed problem of common genetic ancestry and common paideia (education, outlook, culture) continues to pulsate in the debate surrounding nationality, citizenship, and political life at large.

The widespread interchangeable (mis)use of nation/country/population and nationality/citizenship/ethnicity indicates a great degree of underlying confusion. This situation resonates with the schematic, contractual in essence, modern understanding of the terms nation and nationality. Nowadays, most nations are to a larger or lesser extent multiethnic and often rather diverse. Many consist of kaleidoscopic amalgamations of people – both indigenous and immigrant. The very word nation, however, stems from the Latin natio – referring to nativity, to something which is ‘natural’, born and rooted in a particular locus. It denotes a certain – ‘natural’ – level of commonness. How to gauge this natural commonness; to what extent does shared genetic lineage imply a shared worldview and a specific, enduring way of interaction with society and the environment; and then – how does the actively promoted modern-day celebration of ethno-diversity and multiculturalism communicate with the ‘classical’ understanding of nation and nationhood; can the two outlooks be reconciled?

This confusion is not only semantic. In a sense, it reflects the wider, tendentiously polarised over the last century or so, nature vs. nurture debate. The sharp contradistinction between what is natural, innate and genetic and what comes from the environment, upbringing and education has fuelled a great number of controversies and lamentable developments around the globe. It is generally accepted that the phrase nature vs. nurture was coined by the English polymath (and Charles Darwin’s semi-cousin) Francis Galton in the second half of the eighteen hundreds. Among a plethora of notable contributions, Galton is also credited with the creation of another influential term: eugenics. The view that heredity is ‘hard’, conservative, operating around an ‘all-informing’, inflexible core, which is greatly separated from the environment, experience and upbringing, became very influential in scientific, philosophical, political and artistic circles. Theories contrary to hard genetic determinism – putting centre stage the malleability of inheritance, the leading role of experience and choice – also emerged and flourished in popularity.

A climate of extremes ensued. The concept (and rhetoric) of a profound dichotomy between nature and nurture was superimposed over the more flexible and synergistic ‘traditional’ understanding of the matter, markedly polarising and distorting the entire, many-sided debate about the role and weight of heredity and experience in both the natural world and the human situation. In one form or another, this widespread disarray persists to the present day. It reverberates not only in the scientific but also in the political arena, channelled broadly and enthusiastically through the media. The pervasive presence of the sharp separation and confrontation between nature and nurture provides ample breeding ground for radical, manipulative and destructive views, agendas and movements. In this light, the analysis of the current surge in nationalism, xenophobia, racism, isolationism and religious extremism in the West cannot but benefit from a careful, critical consideration of the nature/nurture antagonism. This issue deserves to find a place in the mosaic of pertinent, interrelated problems, which need to be addressed promptly, yet maturely and holistically, if a deeper, multidimensional understanding of the nation- and ethnos-related problems of the day is to be gained.

In 2012 a school in Thessaly, central Greece, elected another Albanian, this time a girl, to bear the national flag in the October parade. The girl’s classmates threatened her with pressure from the far right sector and demanded that she was denied the honour on the grounds that she wasn’t ethnically Greek. The student agreed not to carry the colours, saying that her decision was not motivated by fear but by respect for the flag, the school principle and the teachers. A year later, the election of another Albanian girl – the best pupil in her school in Crete – was also met with public outrage, to which the local teachers’ union president reportedly responded: “This excellent student may be of Albanian origin but she has a Greek citizenship”.

The problem of citizenship and nationality, seen as an issue of ‘natural’ belonging or sharing a level of connectedness and sameness, but also as a matter of education, upbringing, participation in and contribution to civic life (which form and actualise this sharing and belonging), looms as striking as ever over Europe and beyond.

What makes one Greek, British, European or Western? To address this question in earnest, we need to start from the bedrock notion of common humanity – our universal friendship ‘by nature’ – and then, perhaps, rediscover the meaning of the terms nation and nationality, elucidating them and even rethinking them in the light of the possibility for even closer friendship ‘by nurture’.

In this vast and labyrinthine landscape, technologisation and digitisation can provide some help, but surely, they can also intensify the nature/nurture dichotomy, deform the debate and augment the overarching problems. Easily accessible DNA profiling, neurobiological techniques and behavioural research have either began to be employed, or could become prominent factors, in the pursuit for ‘measurable’, monochrome answers to the complex questions about nationality or ethnicity. Considerable care is needed not only in the application of these approaches but also in the interpretation, presentation and dissemination of the generated results – especially so in an environment dominated by headlines-hungry mass-media.

On the wider scientific canvas, however, the advances in biology and medicine have began to draw a more sophisticated, many-layered picture where heredity is characterised with a notable degree of flexibility and openness to the effects of personal or collective experience and the influence of the environment. The scientific discoveries, in the context of a broad, interdisciplinary dialogue, could attenuate the bipolar model of confrontation between nature and nurture and contribute to the debate about nation, nationality and national belonging. Without such an inclusive, multilateral discussion, we risk greater confusion in the political arena, we risk polluting not one a joyful celebration.

1 Comment